James Cook: A relic of boxing fighting to save souls in London's East End

The ex-British and European champion at super-middleweight runs the Pedro club, a retreat from the streets in a part of Hackney that is resisting gentrification – as well as guns, adapted machetes and crack pipes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A long, long way from the Dillian Whyte million-dollar drug debacle of leaks, defiance and confusion, there is another boxing man fighting a drug war from the right side of the ropes in a violent pocket of Hackney.

James Cook runs the Pedro club, once upon a time a sideshow attraction for committee “members” Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, a retreat from the streets in a part of Hackney that is resisting gentrification in the area – as well as guns, adapted machetes and crack pipes. Sure, you can buy fresh sourdough bread but also, in plenty of local shops, a zillion products that belong to another time. It’s an old and a new east London area and the mix can be dangerous.

In many ways Cook is a relic, a frontline warrior, a man from a soppy movie taking a stand against the mean streets that surround his citadel of hope, a former British and European champion at super-middleweight. Each day can be a struggle, a struggle to save souls and a harder struggle to fund the salvation. He often has to get a grand or two from boxing people to pay emergency bills, a fight-trade handout, a backhander in an envelope, to fix a toilet in a building with as many as a 100 people aged between five and 21 in the different rooms. That is just not right.

“What else can I do?” asks Cook. “In an emergency I have to do whatever I can to solve it.” The brief on his MBE back in 2007 mentions his work on “Hackney’s notorious Murder Mile.” That is terrain for the pure hearted to tackle and Cook calls it home.

Cook struggled as a professional boxer in the Eighties to get fights that made cash-common sense. He was not with a major promoter, was too good for easy fights, had to overcome the prejudice that goes beyond being a black fighter with few fans and fought a losing and supposedly lucrative campaign on the road in Germany, France, Holland and Finland.

Cook was ripped off, lost money he was owed from the overseas fights and then had to accept fights that could have so easily made him an eternal opponent, a one-time contender transformed into a punchbag for hire. “There were a lot of hard nights and a lot bad times,” added Cook. He hurt his own cause when he defeated the previously protected Michael Watson, who was seven unbeaten, at Wembley Arena in 1986; Cook had won nine and lost five fights at that point, and had last fought in Britain at the West Midlands Sporting club in Solihull in front of 200 close-lipped, tuxedo-fine private members - it is unlikely they clapped when Cook lost. Cook took up residency in fight veteran Mickey Duff’s “who needs ‘em club”. Duff managed Watson and was not happy with the loss. Cook went back to Europe after the fight to keep working.

He lost a British title fight to Herol Bomber Graham in 1988, then won the super-middleweight title in Belfast, the European version in Paris, retained the title and lost it in France in 1992. He won the British title again in 1993 and retired the following year after losing the title. He was either the British or the European super-middleweight champion during the crazily lucrative years when Nigel Benn, Michael Watson, Chris Eubank and Dubliner Steve Collins made millions, were watched by in excess of 18 million on ITV and won, lost and drew in unforgettable fights for the WBO version of the super-middleweight title. Cook missed out, a disgrace even now.

“What can I say - my face never fit,” Cook offers. “Look at me, c’mon, I’m too good looking for them!” Cook, who was a joy to cover in his fighting days, left boxing with a smile, it is still there on hot, cold, horrible, happy days at the Pedro. It is there this summer, at the open door shaking hands as members fill the club.

Cook and the people that work with him at the Pedro come to work every day, open the doors and count the heads in and out. He has lost members, some dead, others to prison and some have moved on through the vicious shadows. That’s the daily reality for Cook, the motivation behind his one-day-at-a-time approach. He admits it is not always easy, especially when a member has gone and there is no miracle Cook can find to make him come back. Cook is not a magician, there is no glowing wand to alter life on his streets.

“Boxing is ideal here, in this area,” Cook told me last month inside the boxing gym at the club. “It is about discipline and respect. Boxers never take liberties with people. In here, that matters. In here the kids look at successful boxers and it is a motivation. Boxers have a good name.” It is not good for the boxing business or the inspiring business when a fighter like Whyte, shot and stabbed during his years on the street, has so many questions to answer. Cook has been saving men like Whyte for a long time.

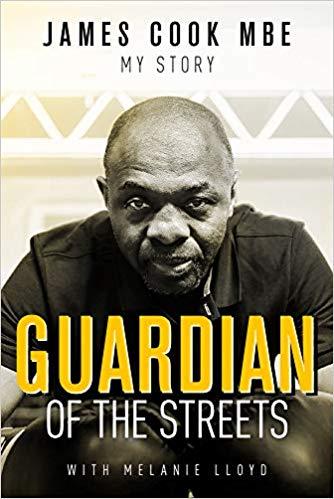

Guardian of the Streets, by James Cook, is out now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments