Donald Curry’s longest fight

Donald Curry was once considered the best boxer in the world, but for the last two decades, the toll of his career has steadily caused his life to unravel. Tom Kershaw speaks to his family; friends; former trainer; protege; doctors; and officials to uncover how one of the sport’s all-time greats slipped through the cracks

Late on a Sunday morning in mid-November, Paul Reyes sat by the phone, fiddling nervously at the gold cross that hangs over his chest, and waited to see whether his call would be answered. It had been almost 24 hours since Donald Curry’s bail bond was posted; another three weeks since the police were called to the small apartment he shares with his sister in Fort Worth, but still the line was silent. For all the dutiful old trainer knew, the ghost of his champion was outside, lost, drifting in the streets.

After a few rings, the phone connected. Curry’s voice led Reyes out into Texas’s autumn sun until he reached a rundown motel that time had forgotten, the type which never moves out of the shadows, and for the next hour, the spirit of boxing royalty flickered again. It can be jarring to imagine how two of boxing’s icons became confined to that bleak room, reminiscing about the past, treading awkwardly around where it’s left the present. They first met in 1968, when a seven-year-old Curry walked into Reyes’s boxing gym with an ability that couldn’t be taught. From that moment on, they had set about conquering the world like father and son. Now, Curry wanted nothing more than to relive the night that dream came true.

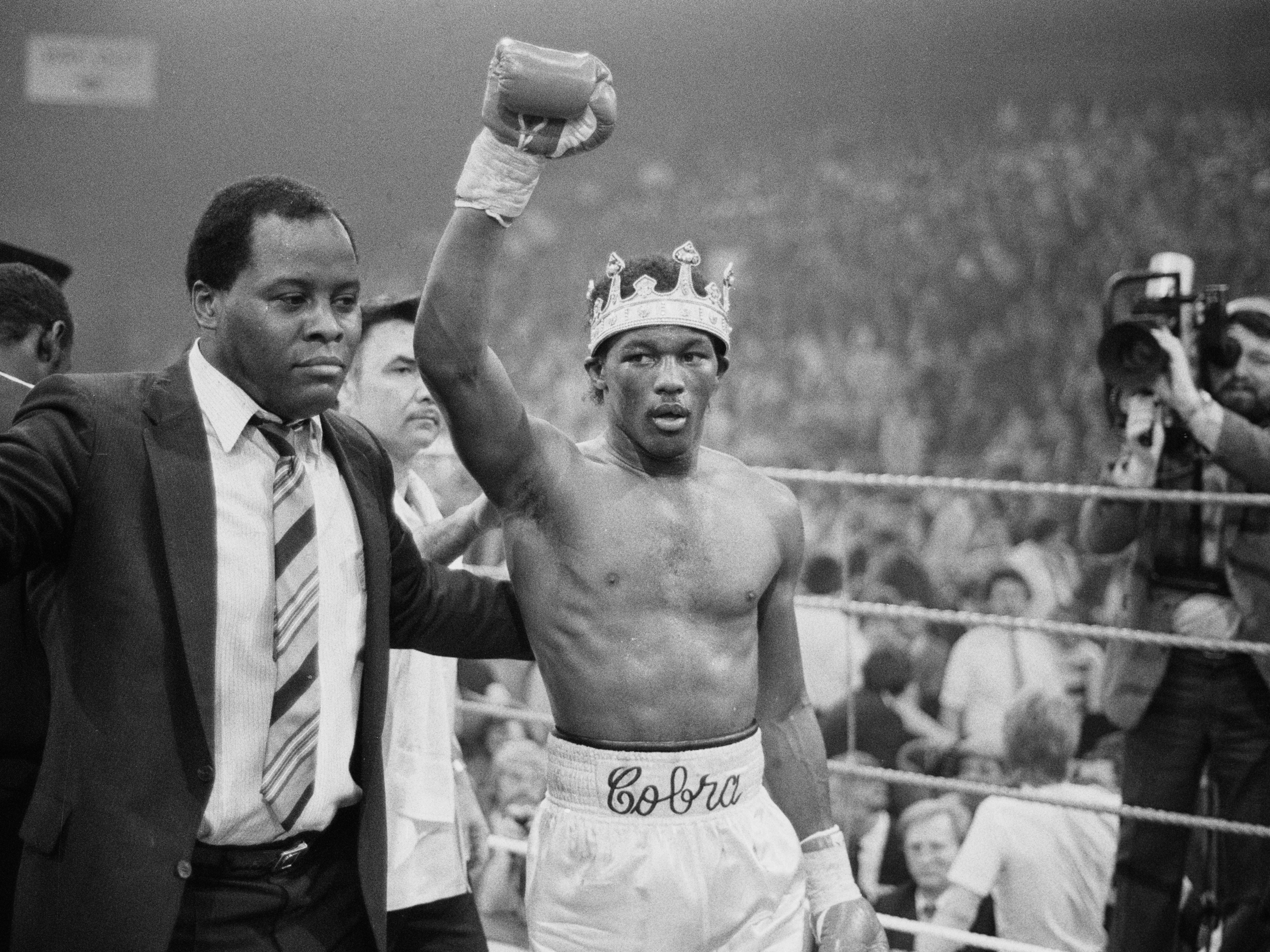

On 6 December 1985, Curry obliterated Milton McCrory in just two rounds to become the undisputed welterweight champion. It made him the best boxer in the world and, for a while at least, he felt invincible. Curry can still recall almost every detail of the fight, right down to the devastating crunch of McCrory’s cheekbone on his knuckles, a left hook so fierce it can travel through time and still elicit gasps. But the distance between then and now has ravaged the memories since.

For the last two decades, Curry is suspected to have been suffering from CTE, a rare brain disorder caused by repeated head trauma. The symptoms often don’t emerge until middle age, starting perniciously before steadily seizing hold over every aspect of a person’s life. Most days, it can seem as though Curry’s mind is still stuck in the ‘80s, presiding over a world that’s long abandoned him. Pride wouldn’t let him explain how he had become trapped in a cycle between bankruptcy and prison, but even then the words might get stuck in the back of his throat. The legacy of his career is one of damage rather than glory. It is hardly a life, let alone one befitting a champion.

“I practically raised Donald, but he’s not the same person, you know,” says Reyes. “It hurts to see him like that. It’s devastating. I believe boxing has let him down badly, not just him but a lot of fighters. All I can say is Donald needs help. I’m glad his son is trying to get it for him.”

****

Donovan Curry rarely used to tell people about his father. There was the teacher at high school who was awestruck; the manager at his first job who asked for an autograph, but aside from that it was more or less a secret. When he was three years old, his mother filed for divorce after Donald had a child with another woman and, as their marriage collapsed, Curry was indicted on a drug conspiracy charge in Detroit. Although he was eventually acquitted, the legal fees decimated the millions he’d earned in the ring and, in 1995, Curry was sentenced to six months in prison for failure to provide child-support payments.

Despite the distance between them, Donovan had always wanted to be close to his father. Growing up, he’d visit him at his aunt’s house on weekends, where he has vague memories of Donald reeling through some of his greatest hits: a gruelling 15-round decision against Marlon Starling; a vicious first-round knockout of Roger Stafford; and of course that defining triumph against McCrory. Once Donovan was in school, although Donald had no car and was living week-by-week on social security income, he made sure to watch his son’s basketball games. But pretty soon, a pattern started to prevail.

“My aunt would call and say your dad’s back in jail, something’s happened,” Donovan says. “The first time I was about twelve. He sent me a letter from Florida and it took me for a loop. I didn’t even know he was there. I used to get frustrated but, when it kept happening, I became hardened to the situation. My aunt would say something was wrong with him, that he was crazy, and they’d get into arguments and the police would be called. I couldn’t understand why he kept getting into trouble, I’d get upset and mad at him, but you still love him and want the best for him. He’s still my dad. He doesn’t mean anyone harm, but his mental state just wasn’t there.”

It wasn’t until Donovan was around 16 that he really noticed an acceleration in how his father’s mind was deteriorating. When they’d speak over the phone, Donald would sometimes ramble for hours on end, jerking from one tangent to the next without any logical train of thought. Donovan would repeat simple things like the name of his school or his girlfriend “five or six times”, only for the words to vanish into thin air. “The one thing he’d remember was my birthday,” Donovan says. “But anything else he’d forget.”

The darkness was slowly but surely devouring at the corners of Donald’s memory, robbing him of the details and emotions, and leaving only the souvenirs and slights of boxing untouched. When he was inducted into boxing’s hall of fame in 2019, Donovan spent hours writing what he hoped would be the perfect speech for his father. They flew together to Philadelphia, spending far longer in one another’s company than had become normal, and the intimacy revealed a bleaker truth. Donald was revered like a “rockstar” by those in attendance, but backstage he jogged to try and maintain a straight line before stumbling over his feet. In uncomfortable flashes, he’d seem to lose all sight of where they were or what day it was. “When he got up to make the speech, he was supposed to talk about his career, all that kind of stuff,” says Donovan. “He just went up onto the stage, said thank you, and then he walked straight off.

“Afterwards, I reached out to psychiatrists, but they didn’t understand. I even asked other boxers, but nobody could point me in the right direction. It was traumatic seeing him like that, knowing he couldn’t do anything for himself. It felt like boxing had hung him out to dry. I just thought how can someone be considered a great, a legend, and then be left to live like this?”

Throughout his childhood, Donovan sought to hide the debris as Donald’s life unravelled. No matter what happened, he would scour the fragments and try to put everything back in place, hoping, praying if the puzzle fit, the cycle might break. But a few weeks ago, when he heard Donald was back in prison after an argument with his sister escalated out of control, Donovan finally decided to ask for help. In a post on Twitter, he explained that his father effectively had nowhere left to live and that the toll of boxing on his brain was being exacerbated with each passing day. “It was the last hope,” he says. “If anything, I just wish I’d done it a long time ago.”

****

Tragedy had dominated Donald’s life long before the start of his own downward spiral. He grew up poor on the south side of Fort Worth with Bruce, his older brother by five years. Their father left before Donald’s memory formed and it wasn’t until several years later that he realised the man who’d filled the void wasn’t his birth father. But Donald was never described as an angry child. His mother, Hazel, referred to him as “the quiet one”.

The more talented of the two brothers, Donald became the rising star of the US amateur circuit, winning national championships from the age of 16. “He had a God-given talent,” says Reyes. “It was never hard to train Donald because he was so good. He could beat anybody. It wasn’t just kids, he was fighting and beating grown men from the armed forces.” Curry was denied the chance to compete at the Olympics after the US boycotted the 1980 Moscow Games and so he turned professional that same year. Even now, his record as an amateur remains remarkable, standing at 400 wins and just four losses, all before his 20th birthday.

In 1983, the Currys became the first brothers to simultaneously hold world titles, but when Bruce suffered a knockout defeat the following year, his state of mind shattered at a shocking speed. A few days after the fight, he confronted his trainer, Jessie Reid, and fired a single shot from a chrome revolver. He was arrested on the same day and charged with attempted murder, but when the case went to trial, Bruce was found innocent by way of insanity and sectioned at a psychiatric hospital in Las Vegas.

Donald’s career never met such an abrupt end, but it wasn’t long after his defining victory over McCrory that it irrevocably lost its course. Curry’s newfound fame incited the more sinister machinations in boxing to crank into life. First, he demoted Dave Gorman, the manager who’d discovered him, funded his training and orchestrated his diet. Not long afterwards, Curry then cut Reyes’s pay in half and limited his influence in the corner. The new voice in his ear belonged to Akbar Muhammad, a former employee of Don King and Bob Arum. The disorder became a fatal distraction. Unfocused and emaciated, having been forced to lose a stone in just two weeks to make the welterweight limit, Curry was still such a favourite against Britain’s Lloyd Honeyghan that several bookmakers refused to take bets on a supposedly routine title defence. The brutal sixth-round defeat he endured remains one of boxing’s biggest upsets. “I blame Muhammad for Don’s downfall,” says Reyes. “After that, Don was never the same. It hurt seeing him take those punches. I wanted him to quit boxing.”

Curry insisted he would fight on, and even won another world title, but his career never truly recovered. His aura of invincibility had been shattered, his speed waned, and every blow left his defence more brittle. In his penultimate fight, against Michael Nunn in 1990, Curry crumpled after being hit with a flurry of fifteen unanswered punches. And when he made a comeback against Terry Norris, although Curry’s mind remained alert, ripping lefts and rights in an effort to claw back time, his body slowly betrayed him. He collapsed to his knees in the eighth round under a blaze of unsparing punches and, as Curry lay there helpless with his head spinning and the strength seeping from his legs, Norris swung a final - and illegal - right hand like an axeman, straight down onto Curry’s temple. He might have announced his retirement in the aftermath, but 30 years later, the repercussions of those punches have never been more devastatingly pronounced.

“I was around 14 when people started to upload his fights on YouTube,” says Donovan. “It’s rough watching those fights back, seeing him get hurt. Even in the wins, he was taking a lot of punches, I see it now. People forget how many amateur fights he had. That’s thousands of rounds. Those blows take a toll on you.”

In the space of six years, Curry was divorced, acquitted, imprisoned and released. He told reporters in Las Vegas that he was “as broke as a joke” and there was little pretence over the motivation behind a last ill-advised comeback. Without Reyes in his corner, Curry agreed to a fight against his former protege, Emmett Linton, for just $30,000. There was hot blood and cold hearts between them, stemming from when Curry used to manage Linton at the start of his career. In 1995, they “got into a little street thing,” Linton says, with a faintly wicked smile. Guns were drawn but not fired. Charges were filed but then dropped. “Ever since then, when Don got out, I knew he was coming for me,” Linton says now, sitting in a doctor’s waiting room in Tacoma. He’s getting a twinge in his right shoulder checked out. “It must be all those punches I threw,” he says before breaking into laughter.

The fight amounted to a grimacing beatdown, with Curry enduring an endless string of punches before the towel was thrown in a minute into the seventh round. “By the time we fought, I knew Don’s skills had deteriorated a long time ago. I sparred with him once before I turned pro and he hit me with a good body shot so I guess he was always confident,” Linton says. “But I did everything right for the fight. I was bigger than him, and I muscled him around. That was my plan and it worked, but his skills were gone. He seemed different. It felt like things had gone downhill, I could just tell. Even the people around him seemed different. He wasn’t that younger, fresh Donald who took on my career.”

There is still a lingering animosity, but over the last few years, the stories Linton has heard from other fighters in Fort Worth have softened him. Occasionally, they’d see Curry standing at a bus stop or walking down the sidewalk. There was that listlessness to him, that Donovan describes as “being a citizen of the United States and nothing more”. There was grey in Curry’s beard and the glint in his eyes was gone.

****

“When the money runs out, friends run out”

Few have as strong a claim to being a city’s proudest son as Larry O’Neal. On his Facebook group, which has more than 122,000 members, the 71-year-old conducts live streams at least twice a day on the current affairs in Fort Worth. He is a cross between a human history book and a de facto sheriff, documenting every detail and charting the heights of its heroes. A former amateur boxer himself, he first met Donald as a teenager and followed him to many of his big fights. “When he knocked out McCrory at the Hilton, I was sitting in the fourth row, just behind Marvin Hagler and Tommy Hearns,” O’Neal says. “Don was one of the most gifted athletes who ever boxed. He was always a caring person and a lot of people looked up to him in Fort Worth. When I found out he was in jail, I said this can’t be, we’ve got to get him out.”

Less than a handful of people have stayed in touch with Donald during his undoing. The hangers-on abandoned on the same tide that washed away his money and it is no secret that, after he retired, Curry burnt many a bridge himself, falling out with younger fighters like Linton, who thought they were being duped. So when Curry’s health began to decline, he was left like an island, slowly sinking without the necessary support. Only his sister, who Donald has lived with for the best part of the last fifteen years, has been a constant presence. “There was nobody looking out for him,” says O’Neal. “After you hit rock-bottom who’s left around to help? That’s the boxing world. The promoters aren’t around to bail Don out of jail or check that he’s gone to the hospital. They can’t make any more money so they’re done with you.”

O’Neal tried to stay in touch, even if he didn’t always get a response. They would meet in Las Vegas sometimes, long after the limelight of Donald’s career had faded, and watch fights from ringside. Each year, he organised the Boxing in Cowtown event, which brought together and honoured old fighters from Fort Worth, with Curry its unofficial guest of honour. “He’s probably been to five of them and most of the time you couldn’t keep him quiet,” says O’Neal. “He wanted everyone to know he was the first world champion in Fort Worth. But the other times, I could hardly get two words out of him.”

O’Neal keeps a museum of Fort Worth memorabilia that he’s made available to the public. A few years ago, a man walked in asking if Curry was going to attend that year’s event. In a pawnshop, he’d found some of Curry’s old robes, his boxing shoes and other personal effects. He wanted to return them for free but, when the man approached Curry, he was told in no uncertain terms that they weren’t of interest. “That wasn’t Don he was talking to that day,” says O’Neal. “There are two Don Currys. When he’s having a good day, he’s more mellow and calm, he takes a little bit of time to process his decisions and makes sure everything he says is correct. But then there’s the other Don, who’s not in control and acts completely out of character. He’s a very proud person. He thinks he’s okay, but he needs help. He’s not the same as when I knew him before.”

When “nobody stepped up” from within the boxing community, O’Neal took the responsibility upon himself. He corralled his online following and quickly raised the $550 bond required to have Curry released from prison until his case goes to trial. The following day, after Curry and Reyes’s reunion at the motel, they met at O’Neal’s office with an attorney. They urged Curry to get a brain scan and a psychological evaluation. “I don’t know what the answer is,” says O’Neal. “If there’s medication or whatever, but it’s a sad situation. He’s my friend and I want him to get help.”

****

It was only after he watched Concussion in 2015, in which Will Smith plays a doctor attempting to convince players, officials and the public about the lasting danger of head collisions in NFL, that Donovan realised his father had been exhibiting almost identical symptoms: forgetfulness; impulsiveness; incoherency; and sudden, unexplained eruptions of anger. The film explains how chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) wreaks havoc in four increasingly severe stages, like a slow burn on the brain that manifests over time. It can be indiscriminate and often go undetected until later life when cognitive and memory issues advance into dementia. A few weeks before his arrest, Donald celebrated his 60th birthday.

Despite the inherent dangers of boxing, the historical research into CTE remains limited. It was first observed in a medical study in 1928, when it was more crudely known as “punch drunk syndrome”, owing to the slurring that would invade the minds and mouths of those it inflicted. Even as high-profile examples became more common, with Joe Louis’ troubled breakdown foreshadowing Muhammad Ali’s physical decline, there were still only 50 confirmed cases of CTE reported in the 20th Century.

There has been a silent complicity within boxing that’s delayed deeper investigation. Fighters are treated as independent contractors and, in spite of any moral obligation, it’s not in the interest of promoters to cast a distressing light on the sport that sustains them. It’s a grave truth that explains how so many boxers, just like Curry, are left in the shade as their families and friends search for answers.

Dr Ann McKee’s research into neurodegenerative disease has formed the main body of knowledge on CTE. From a specialist facility at Boston University, she has identified over 450 cases - around 70% of those recorded anywhere in the world - in the last fifteen years, with a particular focus on former NFL players and boxers. McKee’s index case was Paul Pender, a former middleweight champion, who started exhibiting the symptoms of CTE two decades after he retired in a sequence of atrophy that closely mirrors Donald’s.

“Cognitive issues like forgetfulness; memory loss; and difficulty with organisation that present in middle-age are a very common onset to the disease,” McKee says. “Then, it’s common to develop behavioural abnormalities. They can be violence; a short fuse; anxiety; depression; and suicidal thoughts. It can involve motor symptoms in some people like Parkinson’s; rigidity; or difficulty walking. It’s a progressive disease, that can start even a decade before you see the symptoms, and then accelerates as a person ages.

“It’s very common for people to behave in ways that make them unlikeable or hard to live with because they become irrational and act out. The smallest infraction can make them fly off the handle and have explosive or erratic actions. But the thing that can help families to understand it is that it’s the disease making them this way, it’s controlling their mind and their behaviour, it’s not really them.”

There has been a significant development in scientific research over the last five years. McKee can now use brain scans, imaging and blood tests to better detect CTE while a patient is still alive, even if the diagnosis can never be definitive. There is no treatment that can halt the disease, but medication can be used to ease the severity of symptoms. Yet, the fact remains that countless boxers “are still going to fall through the cracks”.

“They’re a very vulnerable population,” McKee says. “This disease makes it hard to hold onto a job, a marriage or a family. I have the feeling there are a lot more people with this disease than we’re aware of because they don’t have an advocate to get them the healthcare and attention they need.”

There is now at least a willingness from within boxing’s often Machiavellian hierarchy to address CTE and support those who are suffering. Since the ‘80s, championship fights have been reduced from fifteen to twelve rounds and weigh-ins now occur on the eve of a bout, as opposed to the same day, meaning boxers are less likely to enter the ring with extreme dehydration. There are tighter regulations on the padding in gloves and referees are less reluctant to step in and stop a one-sided bout. Medical examinations are far more scrutinising so neurological risk factors are more likely to be discovered. They are vital evolutions, even if their pace has lagged lamentably behind.

After seeing Donovan’s post on Twitter, the World Boxing Council (WBC), one of the sport’s four recognised governing bodies, has attempted to offer their own resources, too. Earlier this year, the organisation partnered with Wesana Health to investigate new medications for those affected by CTE. They have also been in contact with the Cleveland Clinic in an effort to help get Donald a brain scan. “I believe the protocol we are instituting with Wesana can be something of great importance, for prevention, detection and also treatment,” says Mauricio Sulaimán, the WBC’s president.

“My father always wanted to have something to be of aid to the former champions who fall on hard times. Before he passed away, he was fortunate to create the Nevada Community Foundation and this money is used to help situations like Donald Curry for treatment, housing, medicine and for food. We are in the process of finishing the application to have funds for him to help treat him and this case will certainly be approved.”

In time, boxers will see the benefit, and the WBC should be praised for making a concerted effort to be part of the solution. That it is even necessary to do so illustrates quite how far boxing still has to go, and in some senses, for Donald, the help is already too late. “He still thinks he can overcome it,” says O’Neal. “He told the lawyer in my office that he’d already had a CTE scan two years ago but I don’t believe that.”

After watching Curry’s words fail him at the hall of fame in 2019, Donovan did gently confront his father at the airport on their way home and attempt to persuade him to get a scan. “He said he’d do it, but then he said he’s good,” Donovan says. “It’s hard to get someone to do that when they think everything is fine.”

The cycle stayed intact then and is no easier to break now. Boxing gave Curry everything at once, but it has spent the last two decades taking it back piece by piece: the memories stolen; the relationships ruined; the time lost in a ceaseless battle against one opponent that cannot be beaten. This has been the longest fight of Donald Curry’s life, and the greatest tragedy of all is that the odds have always been fixed against him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments