Conor McGregor v Floyd Mayweather: Is the proposed $1bn fight between the UFC star and boxer legally possible?

McGregor and Mayweather are both interested, but as lawyer Jake Cohen explains, there are a number of legal complexities standing in the way of the much publicised $1billion fight

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On the surface, it’s simple. The world’s most high-profile MMA fighter and the world’s most high-profile boxer want to fight.

Conor McGregor, the undisputed star of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), is keen, as is Floyd Mayweather, who remains unbeaten after a storied 49-fight career. The level of public interest is almost unprecedented, as are the figures being thrown about. Any contest between the pair would almost certainly become the first $1billion fight in history.

In reality, the path to any potential super-fight is labyrinthine in its legal complexity, never mind the multitude of administrative and logistical challenges. Mayweather v McGregor has dominated sports headlines for months now and yet one question is yet to be sufficiently answered: is the fight legally possible?

Jake Cohen, a lawyer for Mills & Reeve specialising in legal, commercial and regulatory matters in sport, agreed to talk to The Independent on some of the legal issues that stand in the way of any potential fight, and how these might possibly be resolved.

McGregor’s UFC contract

Mayweather, recently retired from boxing and in pursuit of one final payday, has the luxury of being utterly in control of his destiny. McGregor doesn’t. The Irishman may be the UFC’s brightest star, but he is also their employee, bound to a contract which Dana White, the president of the organisation, has disclosed still has four fights left to run.

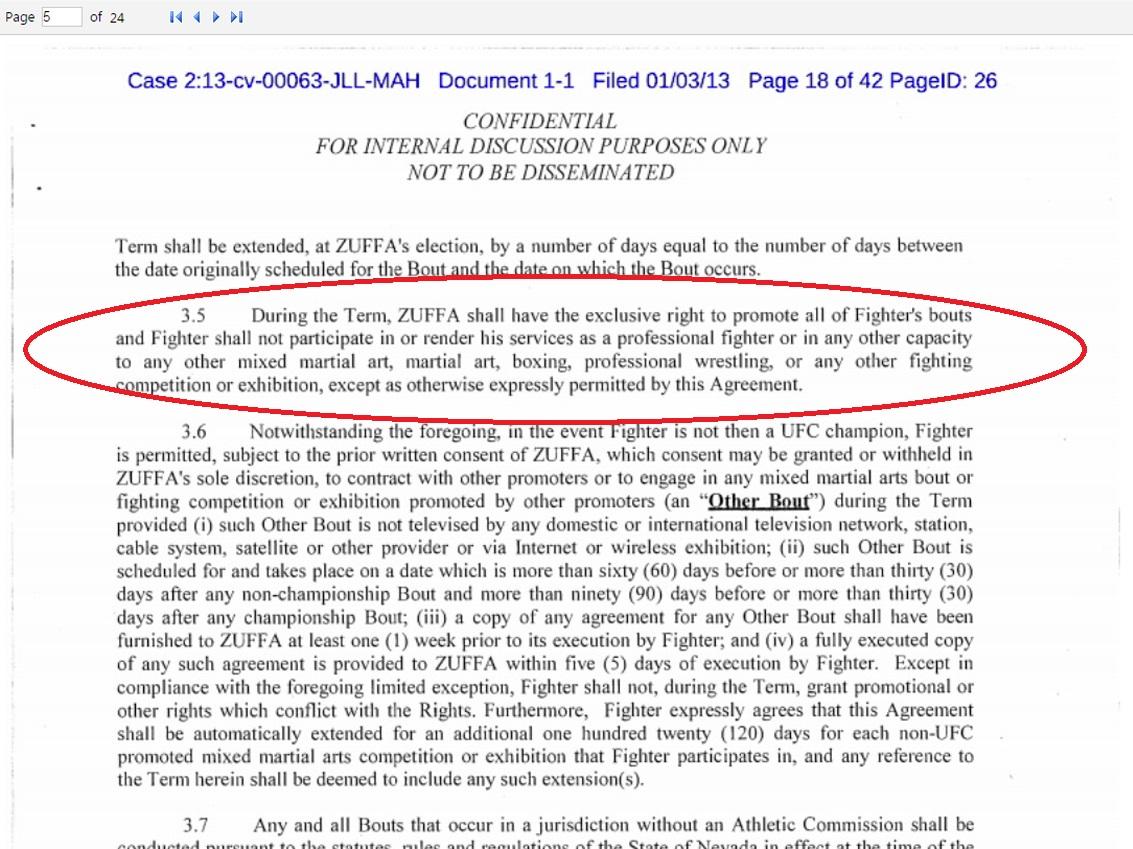

Predictably, the exact terms of McGregor’s contract are not in the public domain. However, as a result of a legal dispute with the Bellator MMA production company, Eddie Alvarez’s contract was published, revealing a deliberately worded exclusivity clause which is almost certainly included in every UFC fighter’s contract:

3.5 During the Term, ZUFFA shall have the exclusive right to promote all of Fighter's bouts and Fighter shall not participate in or render his services as a professional fighter or in any other capacity to any other mixed martial art, martial art, boxing, professional wrestling, or any other fighting competition or exhibition, except as otherwise expressly permitted by this Agreement.

The clause would forbid McGregor (the “Fighter”) from competing not only in non-UFC MMA matches, but also in a professional boxing match. When the UFC and White argue that this fight is not in McGregor’s hands – such as when an unequivocal White insisted to the popular website MMAJunkie that McGregor’s attempts to go it alone would result in an “epic fail” – this is the clause that is being referred to.

Will the UFC decide to play ball?

White has repeatedly changed his stance on the fight, and only last week told the Irish Mirror that “the fight will never happen. It’s not even possible". But with a chance to further push their brand into the mainstream and a potentially record-breaking payday on the horizon, it’s easy to see how the UFC would benefit from accepting a place at the negotiating table.

“Should the UFC enter negotiations we could potentially see something that we often see with boxing, which would be a cross-promotion, in this instance between the UFC and Mayweather Promotions (MP),” says Cohen, who explains that MP – the boxing promotional firm Floyd founded in 2007 – has a precedent for this strategy.

MP and Golden Boy co-promoted nine of Mayweather’s fights after his 2007 victory over Oscar de la Hoya, while his famed 2015 victory over Manny Pacquiao was co-promoted with Top Rank.

“Co-promotion is a common occurrence in boxing and is often the reason for why there is such a long waiting time before these huge fights, because working out the revenue share between these promotions can take some time.

“So the path of least resistance for all parties concerned would likely be for McGregor to agree to work closely with the UFC and MP. Negotiations would naturally still be complicated, due to the estimated $1 billion in revenues this fight could generate. With that much money potentially on the table, every party involved will want to ensure that they receive the largest possible share.”

There is also the – admittedly distinctly unlikely – possibility of the UFC temporarily leasing McGregor’s contract to a third party. “Under UFC contracts that I have seen, the UFC had the power to assign the rights and obligations of the contract to a third party,” Cohen adds.

“If McGregor’s own contract with the UFC contains one of these clauses, and the other parties were amicable to this arrangement, the UFC could theoretically accept a fee from MP in exchange for assigning the rights to one of the fights in McGregor’s contract to MP.”

The founding of McGregor Promotions

There was much excitement at the beginning of February when, in an hour-long interview with respected MMA journalist Ariel Helwani, McGregor announced the creation of McGregor Promotions – his own promotional company.

“Everyone’s got to know their place,” McGregor told Helwani. “There’s Mayweather Promotions, there’s the UFC and now there’s the newly formed McGregor Promotions. And we’re all in the mix.”

But despite McGregor’s positioning of his new venture as a third promotional body, Cohen is sceptical over the influence it will have over any negotiations.

“If McGregor’s contract is similar to other UFC contracts, it is likely that McGregor will have licensed his image rights – which permit the UFC to exploit the athlete’s image, his voice, his signature and even his tattoos for commercial purposes – to the UFC for the purposes of marketing McGregor as a fighter.

“If that is the case, then McGregor Promotions may not be able to exploit those rights beyond traditional individual endorsement and sponsorship deals until the expiration of McGregor’s contract with the UFC. Once his UFC contract expires, McGregor, or more likely McGregor’s image rights company, will be free to license these rights to McGregor Promotions.

“So, establishing McGregor Promotions now could simply be a forward-thinking move to set himself up for the future.”

If the fight moves into the courts

The permutation all parties will be eager to avoid is a lengthy legal battle. UFC will not want to lose the most bankable star on their roster, McGregor will not want to burn his bridges, while the window of opportunity for 39-year-old Mayweather is a perilously small one.

There are many different reasons why the UFC may find themselves forced to dig in their heels, though. Ronda Rousey being one.

For all of the UFC’s many successes over the past few years, the organisation boasts only two genuinely mainstream stars: McGregor and 30-year-old Olympic bronze medallist Rousey. And with the American supposedly on the brink of retirement following two successive knockout defeats, there exists a sentiment within the organisation that McGregor simply cannot be risked.

And of course there’s the money. “Mayweather needs me. I don’t need him. I’m not taking a pay-cut,” McGregor told ESPN’s Sunday Conversation show last year, point blank demanding an equal fee to Mayweather.

Once this pair of $220m deductions are made from the revenue stream (assuming Mayweather accepts a similar fee to the one he took for the Pacquiao fight), along with various other windfalls: where does the UFC’s record pay-day come from? In McGregor, the UFC have a superstar who knows every inch of his worth and who will push them for every cent.

Should McGregor be tempted into pressing ahead with the fight in the absence of the UFC’s blessing, searching for a record-breaking purse, legal action would be an inevitability, as Cohen explains.

“In the hypothetical situation where McGregor declines to fulfil the rest of the obligations under his UFC contract in order to train for and promote a boxing match with Mayweather without the UFC’s consent, then, I think it would be extremely likely that WWE-IMG (the parent entity of the UFC) would file an injunction to attempt to prevent that fight from taking place.”

The Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act

Recent developments would give McGregor a puncher's chance of overcoming any such injunction. On December 1 talk of a fight with Mayweather was reignited by the news that McGregor had been granted a boxing license by the California State Athletic Commission, allowing him to box in the US state.

Many speculated that the development would prove crucial because, by obtaining a license, McGregor might fall under the auspices of the federal Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act, which protects boxers from “coercive provisions” in promotional contracts.

So the theory goes: should a disgruntled UFC attempt to block an announcement of the fight by filing an injunction claiming McGregor to be in breach of contract, McGregor could immediately file for declaratory relief against the UFC, citing that the organisation is restricting him from boxing in a direct infringement of federal law.

Neat though that particular theory is, Cohen is unsure of whether it would prove successful. “It would be for the courts to decide, but there are some potential issues with applying the Ali Act to McGregor’s contract with the UFC,” says Cohen. “Primarily because McGregor’s contract with the UFC is a contract between an MMA athlete and an MMA promoter, whereas the Ali Act specifically refers to boxers, boxing promoters and boxing contracts.”

Another potential issue is that since the Ali Act’s introduction in 1999, it has never before been tested against MMA fighters. "With the Ali Act, I believe I can (promote independently), especially now that there’s offers on the table. But I think it’s smoother if we’re all involved,” McGregor recently admitted.

The idea that McGregor could throw a curveball by retiring from the UFC to fight Mayweather and then promptly returning is also one highly unlikely to succeed, according to Cohen. “In the UFC contracts that I have seen, the agreement essentially pauses when the fighter is out injured, with time then tacked on to the agreement when the fighter returns to fitness. It may be that there are similar protections the UFC have included in an attempt to shield themselves against fighters, quote-unquote “retiring” for this very purpose.”

So despite McGregor’s repeated insistence across his social media accounts that he is the man holding the cards – “Not one of you can do nothing to stop me”, “I run every game” and “Basking in all of my options” are just a handful of his most recent posts – he is ultimately at the mercy of Dana White and the UFC, unless he wants to take his fight to the courts.

And it would appear his chances of winning there are only marginally higher than his chances of winning in the ring. This week it has been the sentiments of McGregor and Mayweather that have been most painstakingly chewed upon and analysed, but in reality it’s the words of Dana White and the UFC that should be paid most attention to.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments