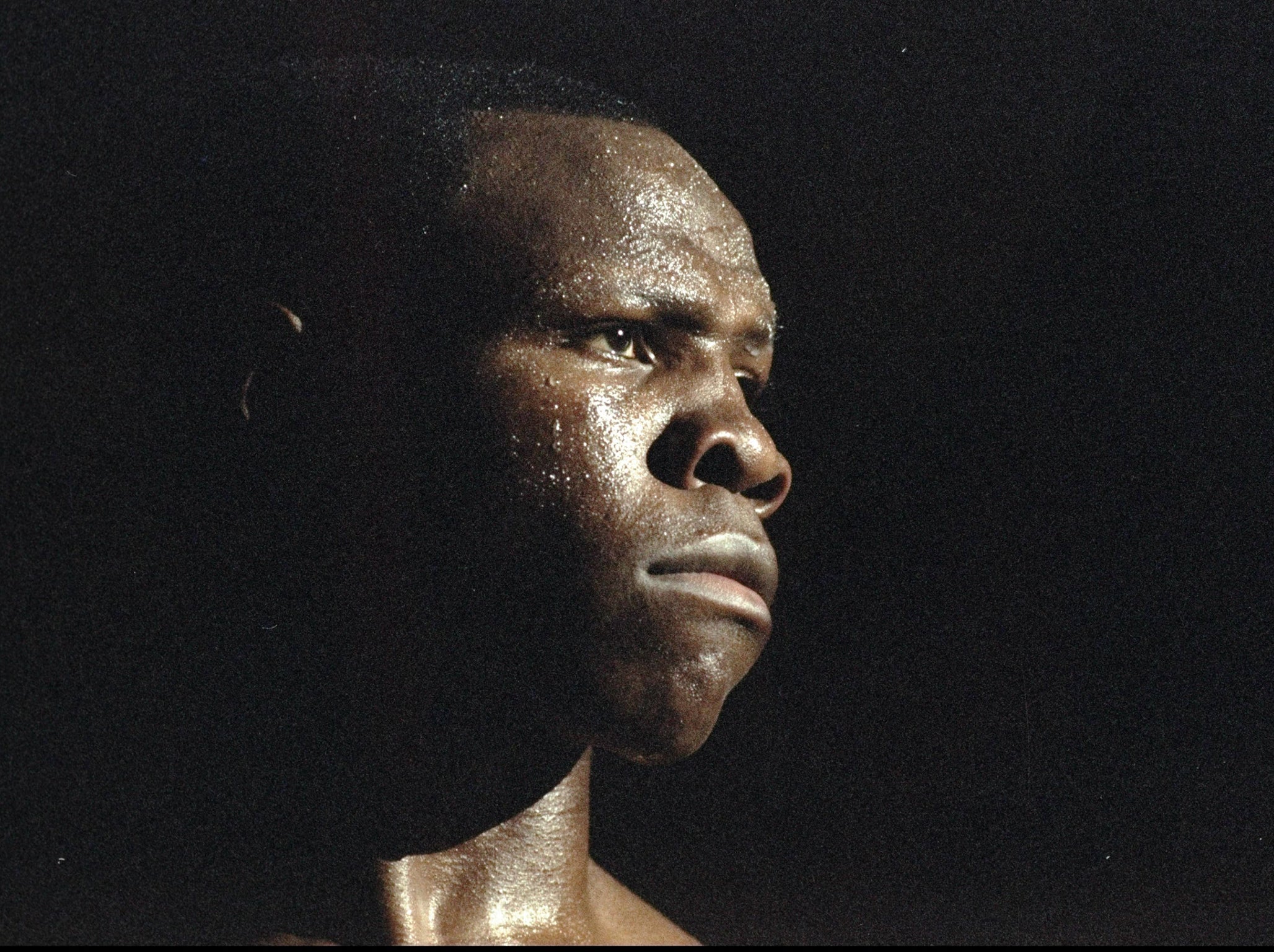

Few boxers could delight like Chris Eubank — now it is time for his son to deliver at the highest level

Profile: While Eubank continued winning during his illustrious career, he struggled away from the ring to create and live the life he wanted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Long before the boxing, the monocle and other absurdities Chris Eubank, the father, was the best thief in Peckham and a sofa-surfing nuisance on the streets of London.

Eubank was also in and out of various homes all over the capital, and one in Wales, during a bleak period when wearing a stolen Burberry coat and getting high mattered to him.

At sixteen he fled to New York on the run from the police and out of any new, bright ideas to survive; he insists he wore his best silk suit for the flight. The flit saved the life of the best thief in Peckham, which was not an easy title to win or defend in the early Eighties.

In New York he dodged bullets after wooing the wrong girl, went back to school and found the boxing gym, where he aggressively fought for the attention of a man called Maximo Perez. “I finally got to work with him but he dropped me, told me I punched like a girl,” Eubank remembers. Eubank never gave up, stayed in the gym, slept in the gym and slowly became a fighter.

He had fought 26 times as an amateur before turning professional in 1985; Eubank won his debut over four rounds, he was just 19, on his own, 250 dollars richer and petrified that night in the forgotten gambling city of Atlantic City. He fought four more times in just over a year, won them all and returned to Britain.

His silk pockets were empty once again when he landed but he had discovered something in New York during the endless nights at the Jerome boxing club: Eubank was a prizefighter and he was good at it.

He settled in Brighton, met a boxing man called Ronnie Davies, a woman called Karron and started to scratch a living on the fringes of the boxing circuit where the neon is dim and prospects limited. He won at Hove Town Hall, a spa in Copthorne and the Guild Hall in Portsmouth and by 1989 he was living with Karron in a room at her mother’s house.

The giant truck, the millions and the full-blown character remained a dream, but the pair were expecting Christopher, their first child. Eubank was still skint and avoiding the police; the loved-up couple had a futon bed and a stray kitten to decorate their privacy.

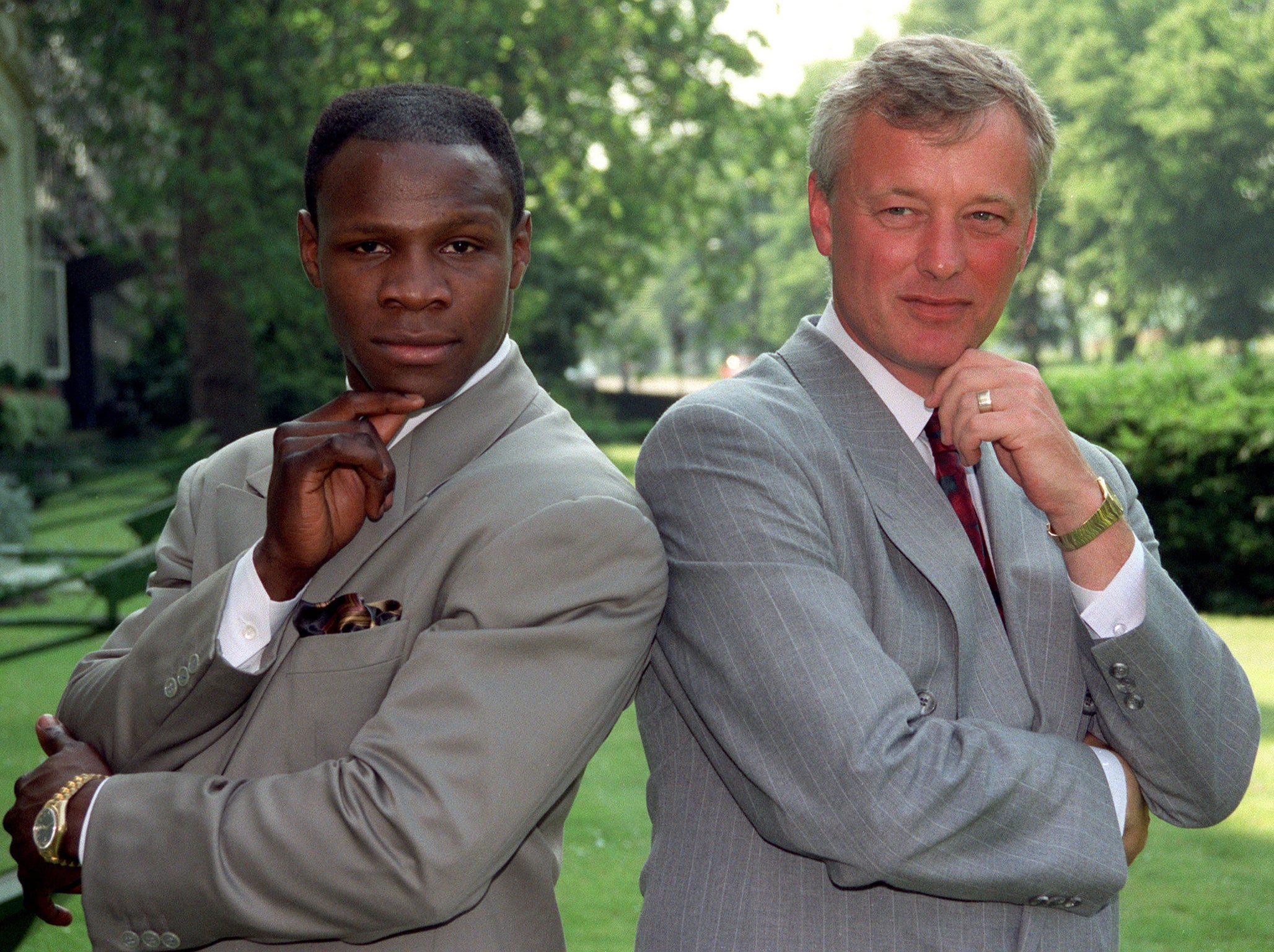

In 1989 I met him one afternoon at the original Matchroom gym in Romford. He was wearing an old-fashioned boxing leotard, the type the real fighters wore and the type of kit seldom found in the glitz and light of the modern boxing gym. “He’s special, very special,” Darkie Smith told me that day.

In those days, a step into one of the few professional boxing gyms was still a step back in time where ancient fighting men like Darkie shaped anonymous men in soiled Lonsdale leotards like Eubank. There was a matchmaker in the Romford gym called Frankie Turner and he did chew on a cigar when dispensing knowledge and refusing fights.

Eubank continued winning in the ring and struggling away from the ring to create and live the life he wanted. He started to reveal the pantomime side, a man I saw seemingly encouraging the raucous disapproval of the fans at the Festival Hall in Basildon in 1989 as his fists humiliated a strong American called Ron Malek.

“Do you really think they hate me?” he queried after I wrote something in the trade paper, Boxing News. I told him “yes”, and he seemed shocked for a moment. However, too many of the boxing press - back then a tight, seasoned and powerful cabal - decided they disliked him. Eubank would often arrive hours late for a press conference, then polish his Harley Davison outside the Savoy for another hour.

“Boxing is a mug’s game,” he declared at the very height of the love-hate game. However, I knew he adored the artistry and beauty of the sport and he still does, his eyes glaze now when he recalls wonderful moments from his brilliant career and it was a brilliant career.

The first world title fight was in 1990, the last in 1998 and they were often unforgettable nights. Eubank fought world title fights twice with Nigel Benn, Steve Collins, Michael Watson and Carl Thompson.

Some of the fights were watched by over 18 million on ITV, 42,000 stood for the Benn rematch at Old Trafford and the pitiful fall-out from the Watson second fight has never faded - it is revisited each time a boxer is in a coma. Eubank was British boxing’s biggest attraction, giving the sport a decade of sacrifice at the highest level. The first Thompson fight might just be the best I have ever seen.

On Saturday night Eubank will be back in a big fight when his son Christopher, known as Junior, meets George Groves in Manchester. “I have taught him in the most cruellest of ways,” Eubank, the dad, said of Junior. “He is spiteful, he has always had that side.” It is the same side his father had and needed during his truly remarkable career.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments