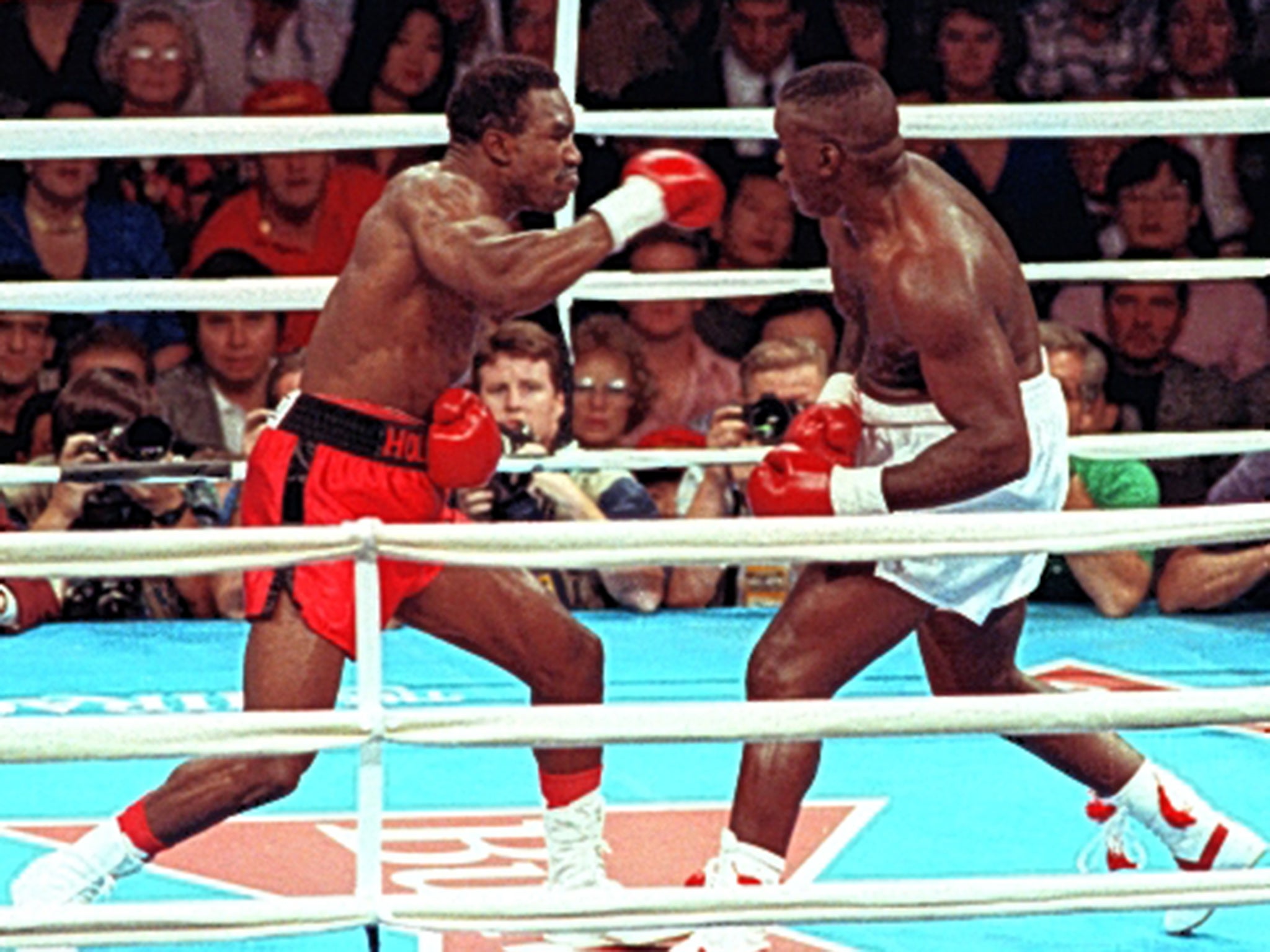

Buster Douglas vs Evander Holyfield: It was the last great heavyweight title fight – and Douglas certainly piled on the pounds

Douglas used the phone in the pine sauna to place an order for $98 of hamburgers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The night when Buster Douglas made $24m and flopped to defeat under a deadly combination of punches and insults is not celebrated often enough.

Douglas had defied sense to beat Mike Tyson on 11 February 1990 to win all the heavyweight belts and then, eight months of comfort, fame and eating later, he lost his world titles to Evander Holyfield in a fight for him to forget in October 1990.

It was an extraordinary year in the heavyweight business, arguably the last time when people cared or knew about the heavyweight champion of the world; the title mattered and meant something.

Douglas had emerged from obscurity and a small-hall existence to topple Tyson in that iconic slugfest in Tokyo at dawn, and during the months before the Holyfield deal was signed and sealed he enjoyed his celebrity. It cost him his desire, his waistline and his reputation.

The boxing career of Douglas had started by default after his college basketball career abruptly ended when he became academically ineligible, which sounds a bit like shorthand for being not quite good enough for the colleges to cook the books on his grades.

He started to box, like his father, and his first outing was in a rigged fight against somebody from the gym his father ran. Douglas was not destined for stardom.

He lost his sixth outing when he fell in love on the morning of the fight and needed to be scraped out of bed just before the first bell. His legs, not surprisingly, deserted him and he was done in two rounds.

His career continued that way until the fight with Tyson, for which he was a 42-1 underdog with some bookies, and that win led to the $60m, two-fight deal with Las Vegas casino owner Steve Wynn.

The days before the first bell of Douglas v Holyfield were savage with comedy and anger. Don King, who promoted the fight with Tyson, finally agreed to a fee just shy of $5m not to be involved in the promotion.

At the same time Wynn, wary of the increasing bulk of his deep investment in the boxing business, put Douglas in a penthouse suite with a sauna to encourage some drastic weight loss. Douglas took full advantage of the phone in the pine sauna, and the room-service menu, to place an order for $98 of hamburgers a day or so before the fight; it was the real breakfast of champions.

On the night of the fight, Douglas was 14lb heavier than he had been against Tyson and went down without much resistance after only seven minutes and 10 seconds. He was booted out of the penthouse the next morning and that was, in theory, the end of the richest fight, which it was at that time, in boxing history.

However, the destructive qualities of boxers never fail to amaze and Douglas, with his pride bruised from insults, slipped out of town and took a six-year sabbatical from the fight game. In his ears he must have heard the referee, Mills Lane, explain to the press late that night that Douglas could have got up. There was also the expert testimony from Eddie Futch, ageing royalty in the boxing business, and his thoughts on the cowardly end to Douglas’s reign as world champion.

Wynn, having paid a total of $34m to the two boxers, lost $2m in total when the books were balanced, but the publicity then, and to this day, from the spectacle was worth every cent.

It seems that Douglas tried acting, villainy and gluttony during his break from boxing and was only really successful at eating; he ballooned to more than 400lb in weight and was hospitalised at one point with diabetes. He also bought a boat, went fishing in Florida and drove around in a convertible Porsche. “I had nothing to prove, nobody to fear,” he said.

Douglas did return to boxing and on the back-road circuit went unbeaten in six more fights. There was talk of one more high-profile outing against Roy Jones, a middleweight genius on his way to winning the legitimate world heavyweight championship. The fight never happened.

Douglas then took a year between fights before ending his career in early 1999, nearly nine years to the day after stopping Tyson’s dominance. He did for a spell appear at autograph signings, smiling, flashing glittering bling and sashaying about in loose-fitting Hawaiian shirts.

He is low-key now, back in his home town of Columbus, Ohio, and growing old slowly. “I’m just enjoying life, still having a wonderful time and here, well, they love me and I love them,” he said.

They might now, but in October 1990 there was very little love for Buster Douglas on the night he surrendered the world title in arguably the last great heavyweight championship fight.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments