Farewell Brendan Ingle: A mad boxing alchemist who shaped his brilliant fighters at great personal cost

Ingle had a brutal but profound awareness of our sport. Something based on raw honesty that caused boxing people, especially estranged fighters, to often choke on his truth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They formed an orderly queue the men that Brendan Ingle made, the known and unknown faces, and in private they have bowed their heads in often tearful tribute to the man that changed their lives forever.

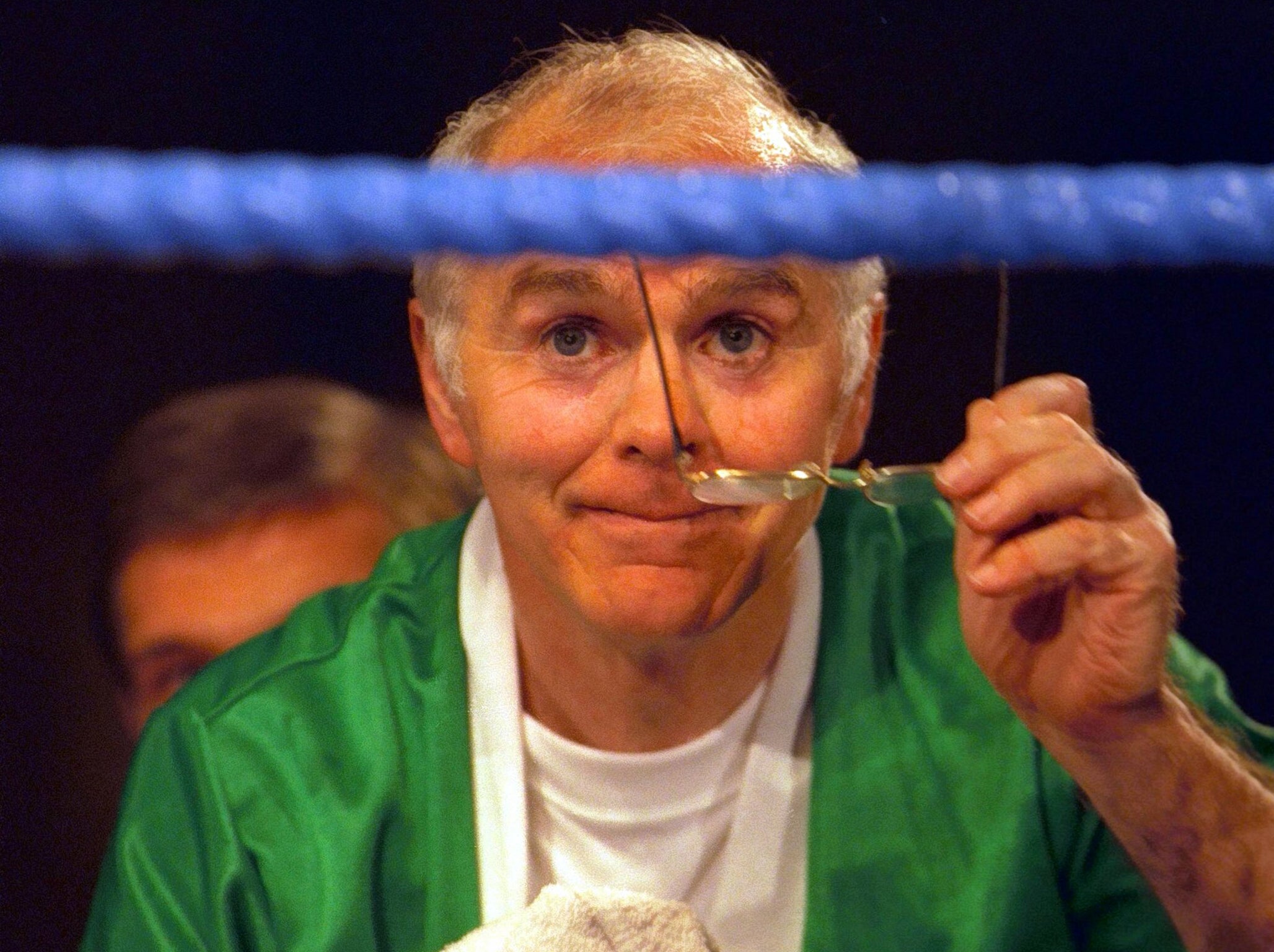

Ingle, the great whispering boxing guru from Dublin, wanted to die in a boxing ring, drop dead in the middle after a fight and he meant it. He nearly got his wish last week: “When that happens youze will all know that Brendan Ingle died happy,” he told me in 2006. He died surrounded by his fight memories.

As a boxer in the late Sixties and early Seventies, he won 19 and lost 14, scrapping for tiny change on a dark circuit of often anonymous nights in forgotten venues. He started his gym when he quit in 1973, an Irish labourer, a hard boxer in love with a Sheffield girl and desperate for some type of better life. He married the girl, Alma, and they took up residency in a corner of Sheffield seemingly stuck in the Fifties.

“When I came from Ireland I had only my boxing gear and the clothes I stood up in,” Ingle recalled one afternoon in Atlantic City. “People helped me and now it’s my turn to help the kids and put something back into a great sport.” At first his fighters were grafters like him, but by the start of the Eighties he had Herol Bomber Graham under his care. The pair of eccentrics complimented each other, creating a style forever associated with that gym and a style that was not always pleasing to watch.

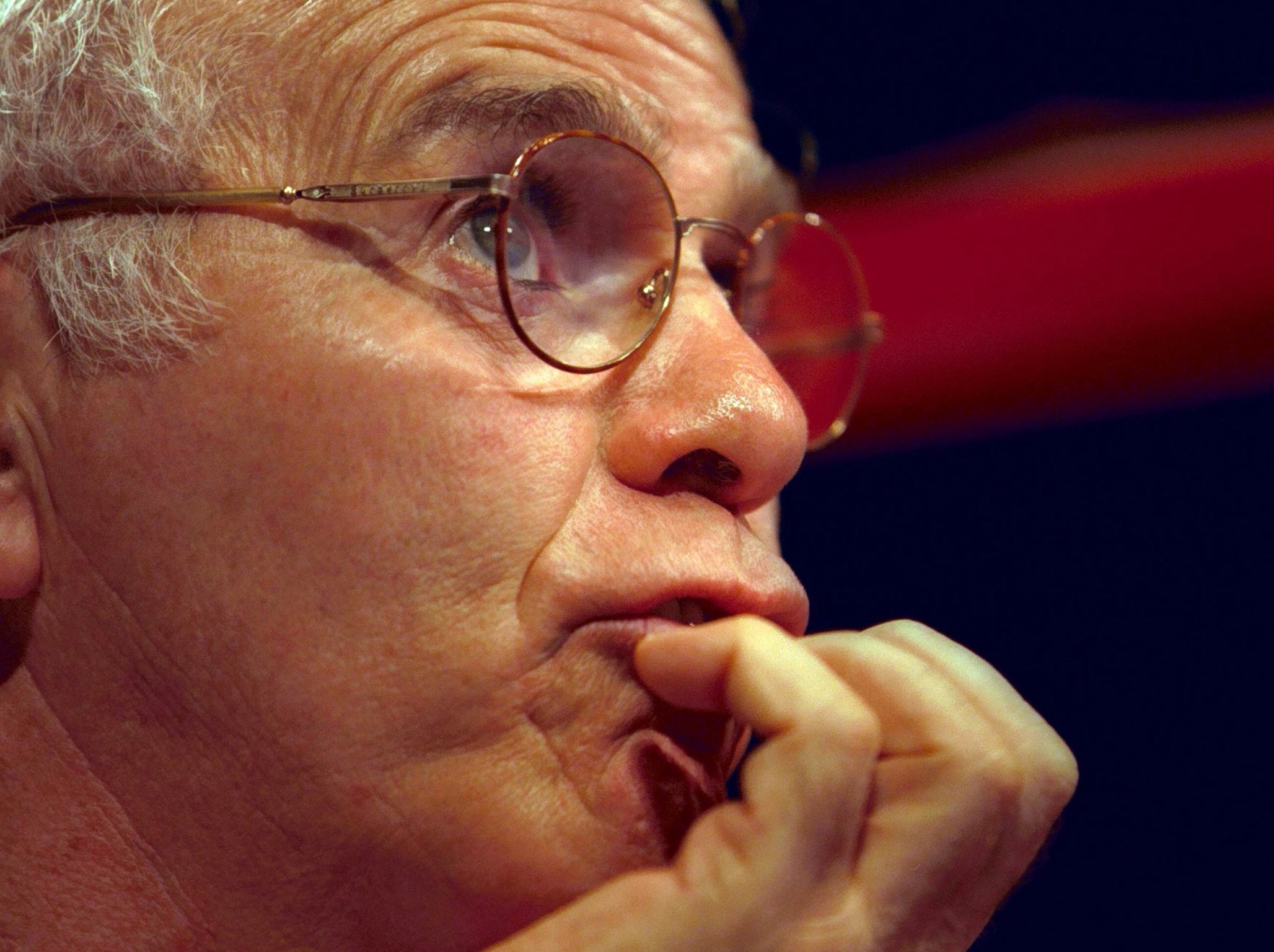

Ingle had hard philosophies on the boxing life, beliefs that often upset the men he did business with and the fighters he had trained since they first arrived at his grubby gym on the hill in Wincobank. He shaped his fighters at a great personal cost; housing, feeding, teaching them, filling in on a life they might have missed and preparing them for the life he had planned. He saved souls does not really say enough, it’s far more complex than that.

However, behind the prose, the neat and tidy tales of redemption and glory, was his brutal understanding of our sport. It was an awareness based on raw honesty and boxing people, especially estranged fighters, often choked on his truth.

“They will pay 10% of 400, even 10% of 2,000, but once it gets to 40,000 or four million they start listening to everybody telling them the same story: ‘Why are you paying that much? You do the fighting.’ Well, I will tell you why: I’ve just spent 15 years, seven days each week and about eight hours each day. That’s why.”

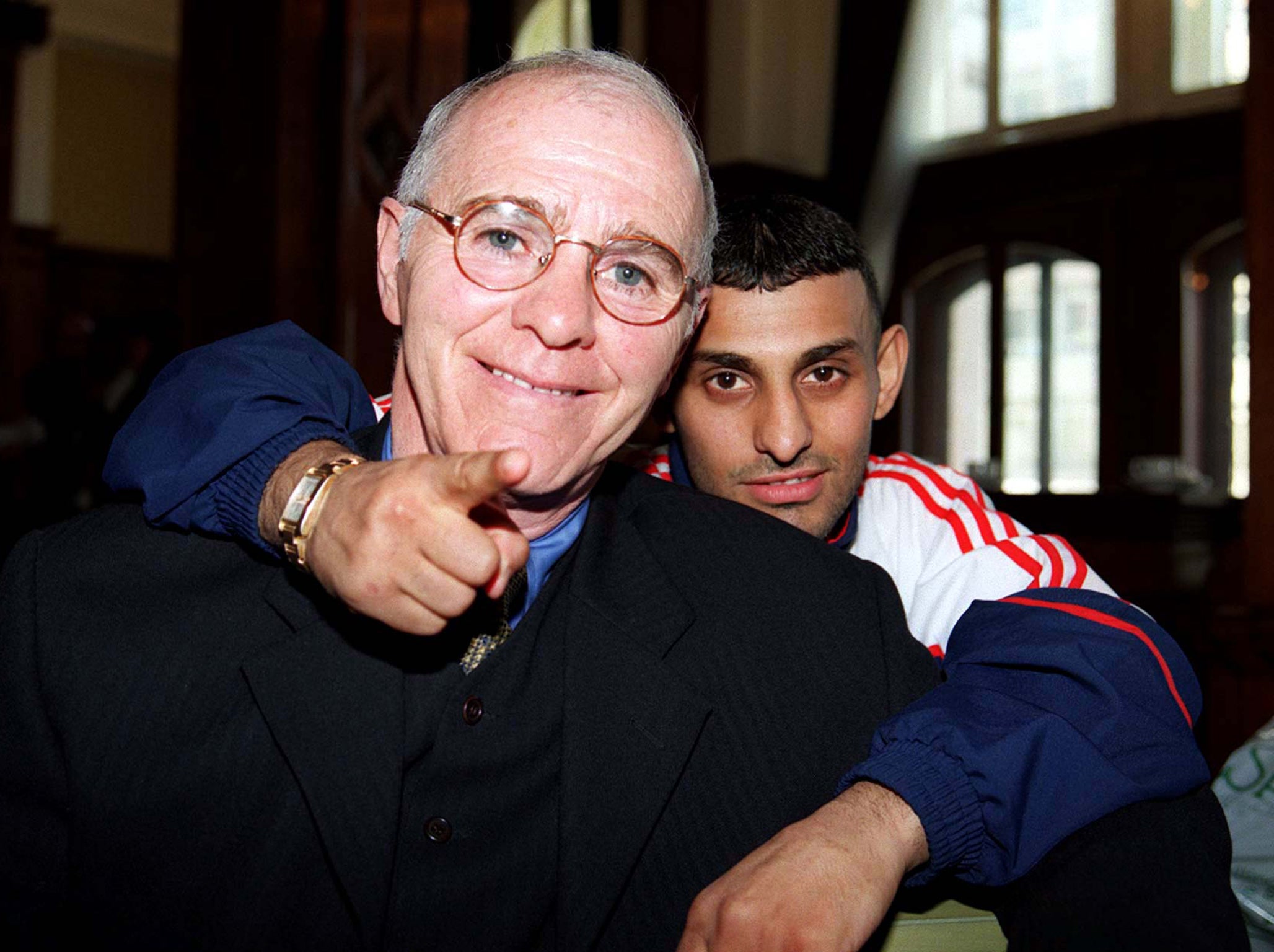

Naseem Hamed followed Graham, dumped at the gym door when he was about seven and forever in Ingle’s tender shadow. Hamed was brilliant from the start, an eleven-year old champion with poise like a veteran. I met Brendan during Hamed’s years as a schoolboy in the Eighties. He remains my favourite, the perfect blend of fighter from deep inside Ingle’s mind; vicious and elusive and cocky.

Each morning after yet another Naz triumph the phone would ring, could be a hotel room or the house before mobiles, and Brendan would dissect the previous night’s exceptional show. “They don’t understand the Naz fella, they don’t know what he is doing - he is gifted,” Ingle would gently preach.

Sadly, Hamed had too many critics and it changed the kid; he was also a victim of the vile whispering from men desperate to take him from the man that made him. Brendan and Naz would eventually split in one of the sport’s tragic separations, a nasty divide that never seemed to heal. “I sacked myself, let’s get that clear,” Ingle said. “I could have continued with Naz and made more money: I’m not a mercenary.”

Brendan remained in the gym, shaping the latest baby to walk into his care. They were often little more than babies, certainly in boxing terms. He had them move along the coloured lines he had put on the gym floor, watched as they mastered their feet; his eye knew early what he was dealing with once they started dancing.

There was always a new Herol or a new Naz in the gym, some kid with a dream as wide as Brendan’s eternal belief in his ability to transform their talent; Daniel, Little Stevie, The Kid, Ezekiel, who could backflip better than anybody when he was eight or nine. I traipsed up that gray hill and through the gym’s doors to witness the early days of many as they worked the taped lines, went through mass and chaotic sparring sessions before either fading away, lost to the city, or making it. The tumbling blur of Ezekiel became Kell Brook, world champion and a contender to this day. Kell is still pushing that door open now, close to 25 years since he first arrived.

There was one kid in about 1996 that got away, a kid so precocious that Brendan turned him professional at just 16 and he had to travel to South Africa, where underage boxers are legal, for his debut. “He can be even better than the Naz fella,” Brendan whispered to me one afternoon. He won the fight, but never made it any further, and was sucked back and vanished into the night; a few years later a nurse I knew in Sheffield treated him for gunshot wounds. They were not his first. Brendan could not save or change everybody, but he tried.

He took his finest and his best scratchers to prisons and working men’s clubs for unique entertainment. I went on several lunatic outings behind bars and to bars to watch as inmates or drunk punters tried to land a punch on any of his fighters. “They can throw everything,” Brendan explained. “The boxers are not allowed to throw a punch back.”

There was always a fallen boxer or two in prison, but they still missed. The best fighters in prison were given Johnny Nelson to hit and they, just like dozens of professionals, failed to land cleanly. Nobody forgets those visits and several inmates became Ingle fighters when they were released.

He certainly found the discarded - social services guided their failures to his door - over the years and he gathered in lost and stray souls. There was, in the days of Naz, a wizened old money lender, who would hit the bags and be be part of the riotous communal spars. A man of sixty plus moving round with Naz, trading insults and body punches only, in a ring packed with a dozen boxers. There was no place like Brendan’s gym anywhere on earth. He often gave his boxers new names, fighting monikers to carry with pride into the ring; he had Paddy O’Reilly (a black heavyweight from Derby), Slugger O’Toole, Tony Montana and Kid Galahad.

They were names that made him chuckle. “The Kid is the latest, not the last,” he warned in 2015. He was still creating, like a mad boxing alchemist, right up until the end.

Brendan and I sat in New York hotel rooms, underground bunkers in the Yemen, a Rotherham miner’s club, in saunas the world over and mostly on his perch by the ring in his gym to talk. I listened, I do that in the presence of greatness and I never lost a word. He made more than just great fighters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments