Doping doctor, athletics whistleblower, boxing coach: The rise, fall and resurrection of Angel Heredia

Exclusive interview: The infamous former scientist, then star federal witness, and now coach to numerous world champions reflects on his past and present since becoming the centrepiece in one of sport’s biggest scandals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The resurrection of Angel Heredia was not simple, for one because he fell so far from grace, yet it begins religiously each morning at 5am. The alarm goes, he dons an indiscriminate tracksuit and steps out into Las Vegas’ hardened sunrise. Waiting at the track is Romero Duno, a lightweight Filipino boxer, who fights Ryan Garcia next month – Mexico’s 21-year-old prince-in-waiting – 15 miles down the strip where dust turns to sequins at the foot of the MGM Grand.

The training is meticulous; web spun by stopwatches, regimens and an alphabet of supplements. For one of the sport’s most successful strength and conditioning coaches, boxing is a science orbiting around invisible margins; not one atom can fall out of place.

A brick-shouldered 6’3” former discus champion, he shouts encouragement as Duno runs sprints and follows a programme of heavy weightlifting, and then recedes to the shadows to watch his sinewed experiment spar in one of the many boxing gyms stitched into the city’s suburbs. “I’m the only guy that changes the odds,” Heredia says. “A fighter is the underdog, but when people find out he’s working with me, the odds change.”

***

10 March, 2005 – Heredia spent a decade manipulating the odds until, finally, they turned against him. For two years, he had evaded the FBI, living under a pseudonym at an outlying Texas A&M University campus in Kingsville. He reigned in plain sight as one of the principal architects of doping in athletics, visited by athletes, accosted by agents and coaches. Twelve of his clients won a combined 26 Olympic and 21 World Championship medals. “Doping is a business,” Heredia says. “If you’re a track athlete running 9.9s, [in the 100m], you might spend anywhere between $20,000 and $50,000 [on PEDs] a year.”

But as he returned from the gym on a suffocating Southern afternoon, two police officers stood by Heredia’s door. As he entered his room, he found the lanky frame of Inland Revenue Service investigator Jeff Novitzky staring back at him. “What’s your relationship with Trevor Graham?” he asked.

Two years before Heredia was finally tracked down, Graham and Balco founder Victor Conte were principal rivals in US track and field. Both – correctly – suspected each other’s athletes of using PEDs. One morning, Graham, who trained the likes of Marion Jones, Tim Montgomery and later Justin Gatlin, posted a syringe containing a designer drug he believed Conte’s athletes were using to the United States Anti-Doping Association (USADA), asking them to investigate under the guise of being a whistleblower.

When Novitzky led an IRS investigation into Balco, he found a crumpled letter written by Conte. It alleged that Graham’s athletes were doping using the help of a Mexican distributor nicknamed ‘Memo’.

Heredia’s cover was blown. A week later, when Novitzky presented his lawyer with a subpoena and evidence linking him to the illegal distribution of PEDs; transcripts of conversations; copies of blood tests; wire transfer receipts and witness statements, he made a plea deal to testify against Graham and avoid a jail sentence, becoming the highest-profile federal witness in doping history.

“All of these guys were friends of mine, we’d known each other for years,” he says. “We still see each other till this day. We say hello, there’s no harm, we’ve all moved on, we’ve got families. Many years knowing each other, then going against each other, it’s tough but I had to make a decision and I did the right thing.”

***

Angel Guillermo Heredia – Memo to his friends – is the son of a chemical engineer, born into a family of doctors in a privileged Mexican neighbourhood in 1975. He excelled at sports before eventually taking up the discus, winning national titles at junior level and harbouring dreams of competing at the Summer Olympics. “When I was young, I was always clean,” he says. “But then I started noticing a lot of my friends and athletes [using PEDs]. When you’re working and training hard every day, it burns on your mind.”

Despite experimenting with PEDs, he didn’t have the stature to reach the elite level – “everyone has misperceptions that you take a pill and become a champion” – and soon became obsessed by the “chemistry” of doping. Over time, he learned how athletes could avoid detection and created new undetectable structures of enhancers as well as graduating with a degree in kinesiology. He describes himself as a scientist and athletes would pay up to $20,000-a-year for his advice, plus $40,000 bonuses for significant victories.

After testifying against Graham in 2007, Heredia continued to work as a federal witness for USADA – The Independent has seen copies of emails between Heredia and Novitzky. “I provided data, substances that were undetectable at the time, how to test EPO, a timeline of testing, how doping was done. Because of me a lot of rules have changed in favour of drug detection.” In addition, Heredia identified 26 PEDs used by athletes that were previously undetectable to testing agencies.

“We make mistakes as humans, we have regrets, we make changes and move on in life,” he says. “I’m grateful that God provided me with a different opportunity, he provided me with a job that I loved and a new life. There’s not a day of my life that I don’t remember what I did was wrong, but that’s in the past and I’ve moved on.

“What I do nowadays, people know who I am, they know I’ve worked with USADA for years, and they know I don’t condone drug use, one: because I walked away from that many years ago and two: because I don’t want to ruin my credibility.”

***

Duno is in the best shape of his career. Just like every fighter Heredia has worked with, every muscle in his body is amplified, the veins angrier, the definition more pronounced. But, 14 years since being confronted by Novizky, Heredia still can’t escape the “clouds of doubt”. “Everybody will always have a perspective,” he says. “I understand science.”

Going clean was his salvation; an escape from the paranoid world he straddled. He changed his surname in an attempt to wipe his slate clean and has spent the years since modelling himself as anti-doping’s guardian preacher, criticising lax testing practices, testifying on behalf of those wrongly accused, and pointing officials in the direction of wrongdoing. Currently, he’s working charitably on behalf of a South African boxer who he’s convinced has been wrongly accused.

“At the beginning, people had their opinions,” Heredia says. “I didn’t come in and expect everyone to believe. But I’ve done a lot for years for anti-doping that nobody has ever done. There’s a lot of ignorance in boxing. People don’t understand the benefits of what I’ve done. I’ve been in boxing for eight years and none of my boxers have ever tested positive. We’ve always been clean. That was a change of life for me. I have my family and my son. This is what I make for a living and I don’t want to taint it.”

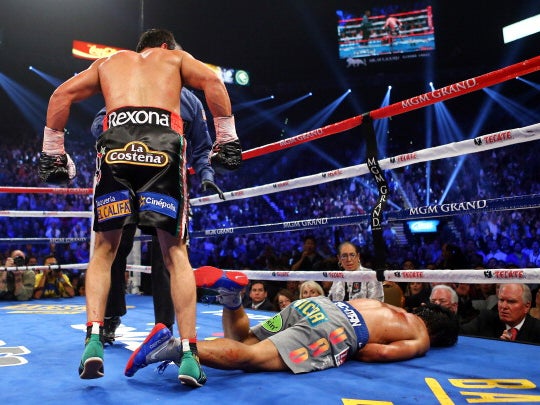

The rebirth began in 2011 – two years after Usain Bolt distanced himself from speculation that he’d worked with the coach in the build-up to the World Championships. After being reunited with childhood friend and renowned boxer Jorge Arce, Heredia guided the 6/1 underdog to a world title. Later that same year, he contacted Juan Manuel Marquez, one of Mexico’s all-time great fighters. Over the course of 11 weeks, Heredia transformed Marquez “into a beast” and in the sixth round, the 36-year-old knocked out Manny Pacquiao in one of the sport’s most memorable upsets.

“I’m attacked for my past but, frankly, I’m the cleanest guy in boxing,” he claims. “There’s a lot of cheaters in boxing and I don’t blame them because the system is so bad, but in boxing you can kill someone. A few high-profile boxers have approached me trying to get dopes. I tell them I don’t do that anymore.” That hasn’t, however, stopped Heredia from being dogged by a permanent trail of suspicion.

The Independent has seen correspondence between Heredia and Mauricio Sulaimán, the head of the WBC – one of boxing’s four established governing bodies – asking him to become an instrumental figure in their Voluntary Anti-Doping Association (VADA) Clean Boxing Programme, to help formulate stricter testing and help identify new PEDs being used in the sport. “I’m not going to do the drug testing organisation’s jobs,” he rebuts. “It’s an endless war. I’m not the one getting paid to solve the problem.”

Heredia is enlightening and combative on the state of doping in sport today, skipping between problems blighting boxing, track and field, and football – “A lot of problems in soccer,” he adds. “There are many substances that can leave your body in 48 hours and not enough testing. EPO will leave your system in three days.”

Speaking days after Christian Coleman claimed the 100m at the World Athletics Championships in Doha with a time of 9.71s, Heredia says there is a “red flag” over the American and that missing three tests is “unacceptable”. USADA decided to drop charges against Coleman due to a technicality over dates. Coleman has since sought a public apology from USADA. Heredia adds that, in his mind, “there’s no doubt” that a significant number of athletes at the event were using PEDs.

“On the black market, the drugs are cheaper,” he says. “There’s always new chemicals coming out in China, India, supposedly for research purposes. From one structure you can make 20 for research purposes and there’s no data on them. Doping is more sophisticated, it’s harder to detect, the testing isn’t consistent and there’s no transparency. There’s always going to be a question and athletes who are clean will look dirty. It’s a war that is almost impossible to win.

“The IAAF is always talking about testing. Look at Sebastian Coe, how stupid and ridiculous he looks. I used to respect him as an athlete, I looked up to him as a kid, but he’s never cleaned this sport. What is he talking about? Maybe he cleaned himself when he washed, but not this sport.”

Heredia agrees, in the wake of Alberto Salazar’s ban, that the enticement of large endorsements from the likes of Nike and Adidas “puts pressure” on athletes to deliver results and that training camps in Africa are a circus for suspicion to insiders. “I know many agents who would go to Kenya, sign guys and use enhancements to increase their ability and chase world records. Agents get a percentage. Athletes in Kenya can’t even afford any of those enhancements, especially EPO. There are situations where the agents will abuse people’s ignorance and have athletes use it.”

He can discuss these issues for hours on end. You also get the sense that there are many more secrets buried, far more things he’s witnessed hidden, that he won’t ever tell to a journalist. In one sense, he’s still cautious, the past forever playing on his mind, still married by reputation to sport’s murkiest corner. On the other, he’s fighting against his past, leading a conflicted crusade for a cleaner sport. A life still encapsulated by sporting success, but no longer waged at all cost. As he looks to guide Duno to an odds-defying upset, he believes he's finally found freedom on the other side of the ropes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments