Stargazing in September: Seeing double

Most of the stars we see at night have a companion, or two or more associates nearby, writes Nigel Henbest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s a lonely life, being a star, you might think. Look up at those specks of light in our night sky, each so tiny and so remote from the others. Put in some numbers, and it seems even more dire – the Sun’s nearest neighbour is 40 trillion kilometres down our cosmic street.

But our Sun is actually unusual in living a solitary existence. Most of the stars we see at night have a companion, and in many cases two or more associates living nearby. But the members of a stellar family are usually so close together that you need a powerful telescope to separate them. In many cases astronomers have only discovered that stars are closet doubles by splitting the light in a spectrum of wavelengths, and noting that the dark lines in the spectrum are doubled up.

Other stellar pairs or siblings give each other more space. Our galactic neighbour is a trio of stars. From the southern hemisphere, Alpha Centauri appears as the third brightest star in the night sky. Through a telescope you can easily see it’s a pair of equally brilliant orbs; and there’s a third member of this system which lies several moon-widths away across the sky, and so dim you need a telescope to see it at all. This is Proxima Centauri, the nearest of the three, at 4.25 light years from the Sun.

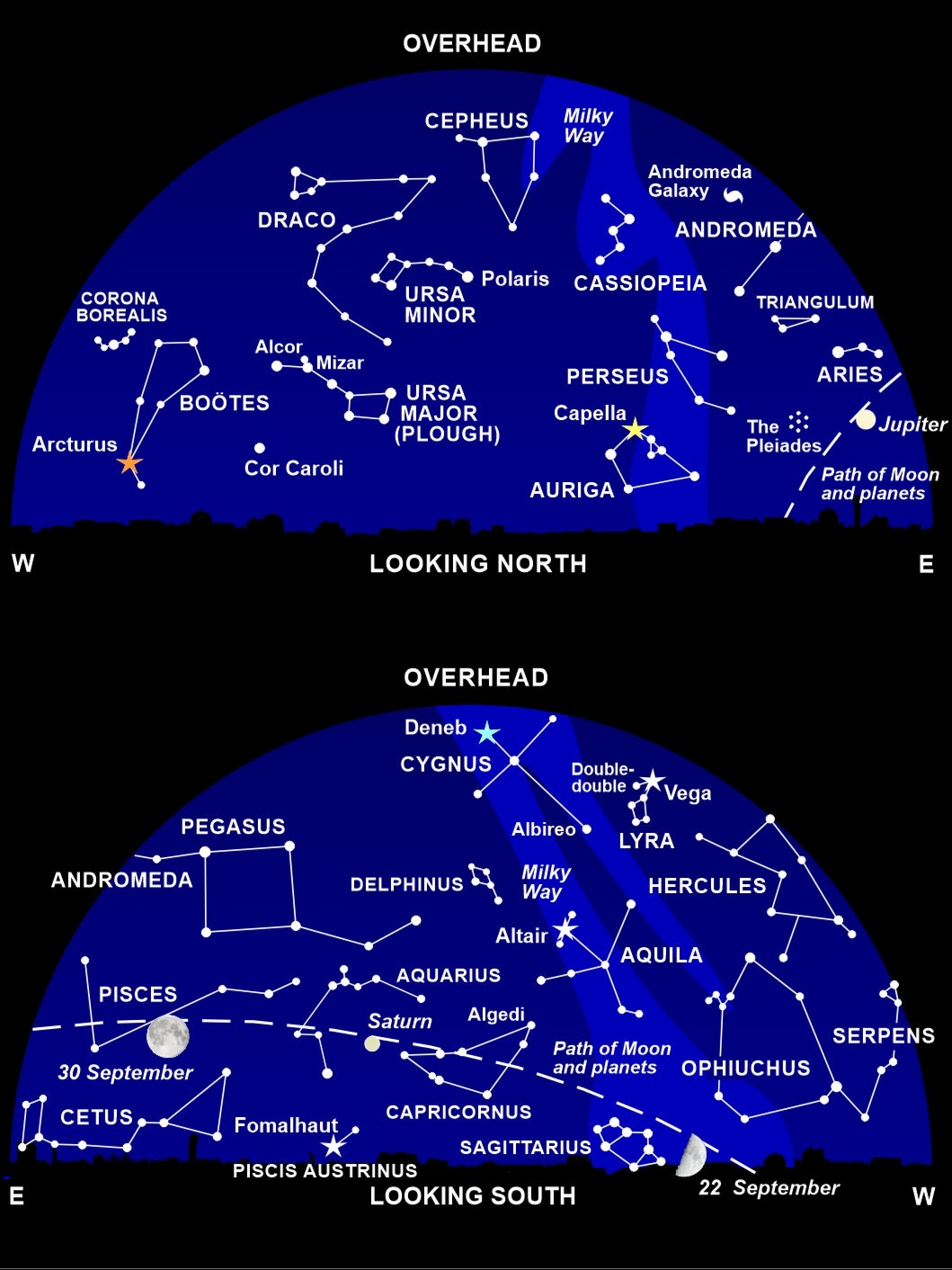

From the northern hemisphere, we’re treated to a lovely stellar pair that you can make out with your naked eye. Look at the familiar shape of the Plough – the seven most prominent members of the Great Bear (Ursa Major) – and you can see that the second star in from the end of the handle has a faint companion. Officially named Mizar and Alcor, this unequal pair has also been long known as the “horse and rider.” These stars lie 80 light years away, and travel together through space. If you have a small telescope, you can see that Mizar itself is a close double.

Towards the southern horizon tonight, seek out Algedi at one end of the boat-shaped constellation Capricornus, seen by the ancients as a combination of a goat and fish. On a clear night, your unaided eyes will reveal that Algedi is a double star, with its components closer together and more equal in brightness than Mizar and Alcor. But these stars are not truly linked. The brighter star lies 105 light years away from us, while the other is 572 light years away. It’s just a cosmic coincidence that they line up as seen from the Earth.

The Double-double in the constellation Lyra is certainly a true stellar family. It’s also a celestial eyesight test chart. If you are young, with 20/20 vision, you’ll easily see this star is double, the components of almost equal brightness. But as we grow older, we lose the ability to see close points of light so distinctly; anyone over 60 will struggle to see this as more than just a single star.

Grab a pair of binoculars, and you’ll easily separate the stars. And a good telescope reveals that each member is itself a closely matched pair of stars – hence the common name of the Double-double. (More formally, it’s known as epsilon Lyrae.)

My favourite double star does require telescope – but it’s worth it! Albireo marks the head of Cygnus, the swan, as it flies along the Milky Way. To the naked eye it’s a single star, but give it a bit of optical power and Albireo becomes a pair of sparkling jewels – a brilliant topaz and a sparkling sapphire set against the sable velvet of the midnight sky.

What’s Up

During the first few days of September, our morning skies have a visitor: the much-hyped Comet Nishimura. The good news is that it’s expected to be naked-eye brightness when it passes closest to the Earth on 12 September and then heads on to its closest encounter with the Sun five days later.

And the bad news? Even at its best, Comet Nishimura won’t any brighter than the stars of the Plough. And it’s low down in the dawn twilight, so you’ll be struggling to see it through a great thickness of atmosphere and against the dawn glow.

Binoculars are your friend here. For a few mornings starting from 7 September, go outside at 4 am and look to the north-east to spot the Plough and – to the right – the twin stars Castor and Pollux. Sweep your binoculars along the horizon between these celestial signposts, and with a bit of luck you should be able to pick out the fuzzy glow of the comet with its tail stretching upwards.

You can’t miss Jupiter this month, rising at 9pm and blazing for the rest of the night far more brilliantly than any of the stars. Saturn lies well to the right of Jupiter, and about the same height above the horizon; thought it’s 20 times fainter than Jupiter, Saturn is still prominent as it’s in a region of faint stars.

Both these gas giant planets are a treat when you see them in a small telescope. As well as Jupiter’s four major moons, you can make out the stripy clouds in the planet’s atmosphere and the Great Red Spot, a vast storm that may have been blowing for 300 years. Turn to Saturn for an unforgettable view of its magnificent rings, and its giant cloud-shrouded moon Titan.

The most distant giant planet, Neptune, is at its closest on 19 September, but you’ll need suitable software to locate the planet and binoculars or a telescope to see it.

Early birds will be treated to Venus as the glorious Morning Star. The crescent moon forms a lovely pair with Venus on the mornings of 11 and 12 September. Towards the end of the month, Mercury appears low on the pre-dawn horizon, well to the lower left of Venus.

The southern sky is dominated by a large square of stars, depicting the flying horse Pegasus, with a line of stars on its left representing the princess Andromeda. To the right of Pegasus you’ll find the small but perfectly-formed constellation of Delphinus (the dolphin).

And below Pegasus swims a group of watery star-patterns: Capricornus is half-fish, half-goat; Cetus depicts a sea monster; while Pisces is a pair of fishes tied at the tails by a ribbon. Aquarius – currently harbouring Saturn – is the celestial Water-Bearer, pouring a stream of liquid down to the star Fomalhaut, the gaping mouth of the southern fish (Piscis Austrinus).

Diary

12 September, early hours: Moon near Venus

15 September, 2.40am: New Moon

18 September, early hours: Venus at maximum brightness

19 September: Neptune at opposition

22 September, 8.32pm: First Quarter Moon; Mercury at greatest elongation west

23 September, 7.50am: Autumn equinox

26 September: Moon near Saturn

29 September, 10.57am: Full Moon, supermoon

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments