The brightest stars in the sky are tearing planets apart, study finds

Unusual planet helps solve mystery of where all the hot, Neptune-sized planets are

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The brightest stars in the night sky are ripping planets apart, according to a new study.

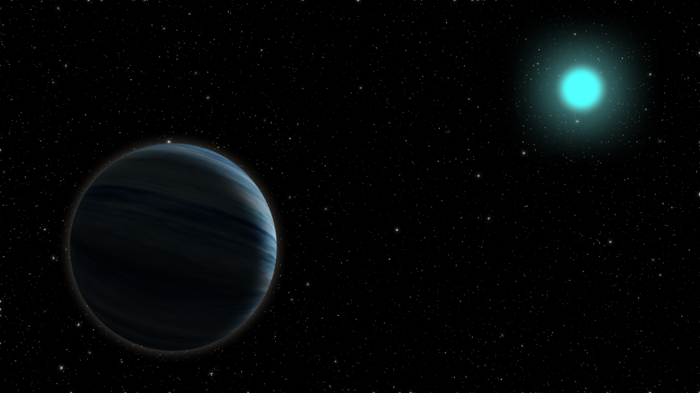

That is the suggestion by researchers who discovered a new, very unusual planet, named HD 56414 b.

The planet orbits around a hot, short-lived A-type star. Scientists generally do not find gas giants smaller than Jupiter around such bright stars.

In recent decades, astronomers have found thousands of exoplanets around a variety of stars throughout our galaxy. Almost all of them – more than 99 per cent – orbit around smaller stars, going from small red dwarfs to those a little more massive than our average-sized Sun.

But more massive stars tend to be all alone, with few exoplanets found around objects such as A-type stars, which represent some of the brightest stars in our night sky. Most of the exoplanets that are found are relatively huge, the size of Jupiter or even bigger.

The new planet could help give a clue about why that is the case – in part because it was difficult to find. Most exoplanets are discovered by watching for the dips in light that happen when they pass in front of their stars, which mean that those most commonly found have short and fast orbits.

But the new planet has a relatively long orbital period. That may be because those that are easier to find would also be closer to their A-type star – and in so doing would have their gas torn off by their Sun, leaving behind just a core that would be impossible to detect.

Scientists have suggested this before, for redder stars. But it was difficult to know whether it extended to hotter stars, because so few of them have planets.

“It’s one of the smallest planets that we know of around these really massive stars,” said UC Berkeley graduate student Steven Giacalone.

“In fact, this is the hottest star we know of with a planet smaller than Jupiter. This planet’s interesting first and foremost because these types of planets are really hard to find, and we’re probably not going to find many like them in the foreseeable future.”

A paper describing the findings has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments