Stargazing in June: A tale of proper motion

Astronomers call a star’s slow creep across the sky its ‘proper motion,’ writes Nigel Henbest. Because of the stars’ proper motions, the shapes of the constellations will change over the millennia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We all know Edmond Halley because he’s immortalised by the comet that bears his name, but to astronomers he has a second claim to fame: he was the first to show that the stars appear to move across the sky.

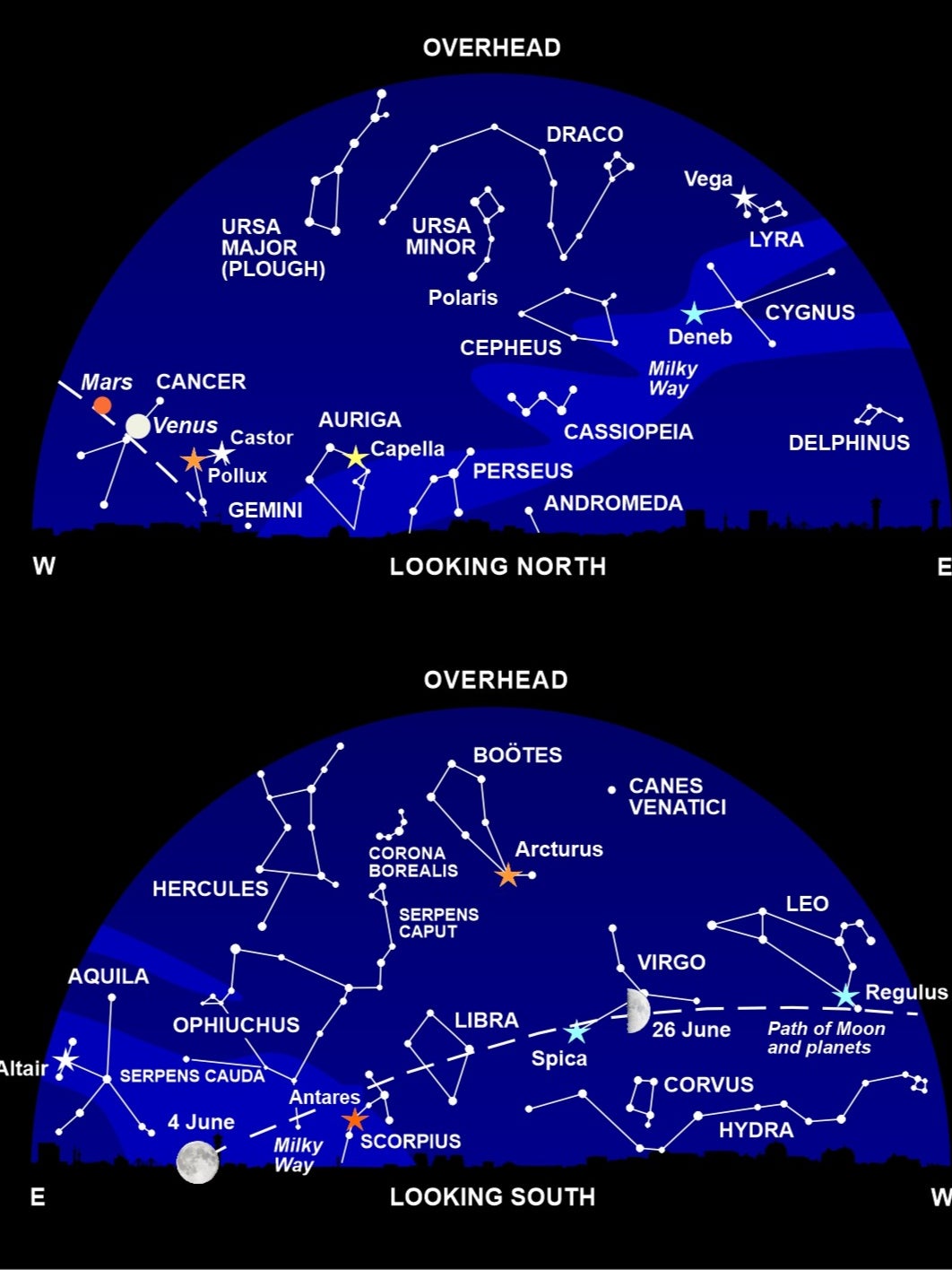

Look at bright Arcturus in the sky tonight – you can find if by following the curve of the handle of the Plough – and you’ll see it’s at the base of a kite-shaped constellation called Boötes (the Herdsman). In 1718, Halley announced that Arcturus has moved downwards in the sky by the apparent width of the Moon since the time of the ancient Greek astronomers: around 1800 years earlier they had seen Boötes as a much squatter kite.

It was a huge step towards our modern view of the cosmos, that the stars are other suns, each pursuing their own paths through space.

Some historians have claimed that Halley’s claim was spurious. Arcturus does move as he said, and so does Sirius – the brightest star in the sky – which was also on his list of moving stars. But Halley also published similar (or even greater) shifts for the bright stars Aldebaran and Betelgeuse, both stars so distant that have hardly moved at all since ancient Greek times. Two out of four correct – was that merely good luck?

Clearly, the Greek astronomers had cited incorrect positions for Aldebaran and Betelgeuse, so it’s perhaps fortuitous they put Arcturus in the right point in the sky. Though I’m sympathetic with the sceptics on these three stars, I’m convinced that Halley was indeed the first to measure a star’s proper motion – not in the case of Arcturus, perhaps, but certainly for Sirius.

In an often overlooked part of Halley’s publication, he compared the positions of Sirius in two highly accurate catalogues, just over a century apart. The earlier had been compiled by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1598, and the second had just been prepared by the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed. (Halley had got his hands on Flamsteed’s unpublished catalogue with the help from his pal Isaac Newton.) Halley proved that Sirius had moved southwards by an amount that couldn’t be explained by any error made by these two meticulous observers, and came up with an answer very close to the modern value.

Astronomers call a star’s slow creep across the sky its ‘proper motion,’ as opposed to the apparent movement of all the stars as the Earth rotates and moves round the Sun. Because of the stars’ proper motions, the shapes of the constellations will change over the millennia. Boötes will become a longer and thinner kite; the handle of the Plough will bend downwards; while the W-shape of Cassiopeia will twist into a triangle with a central star.

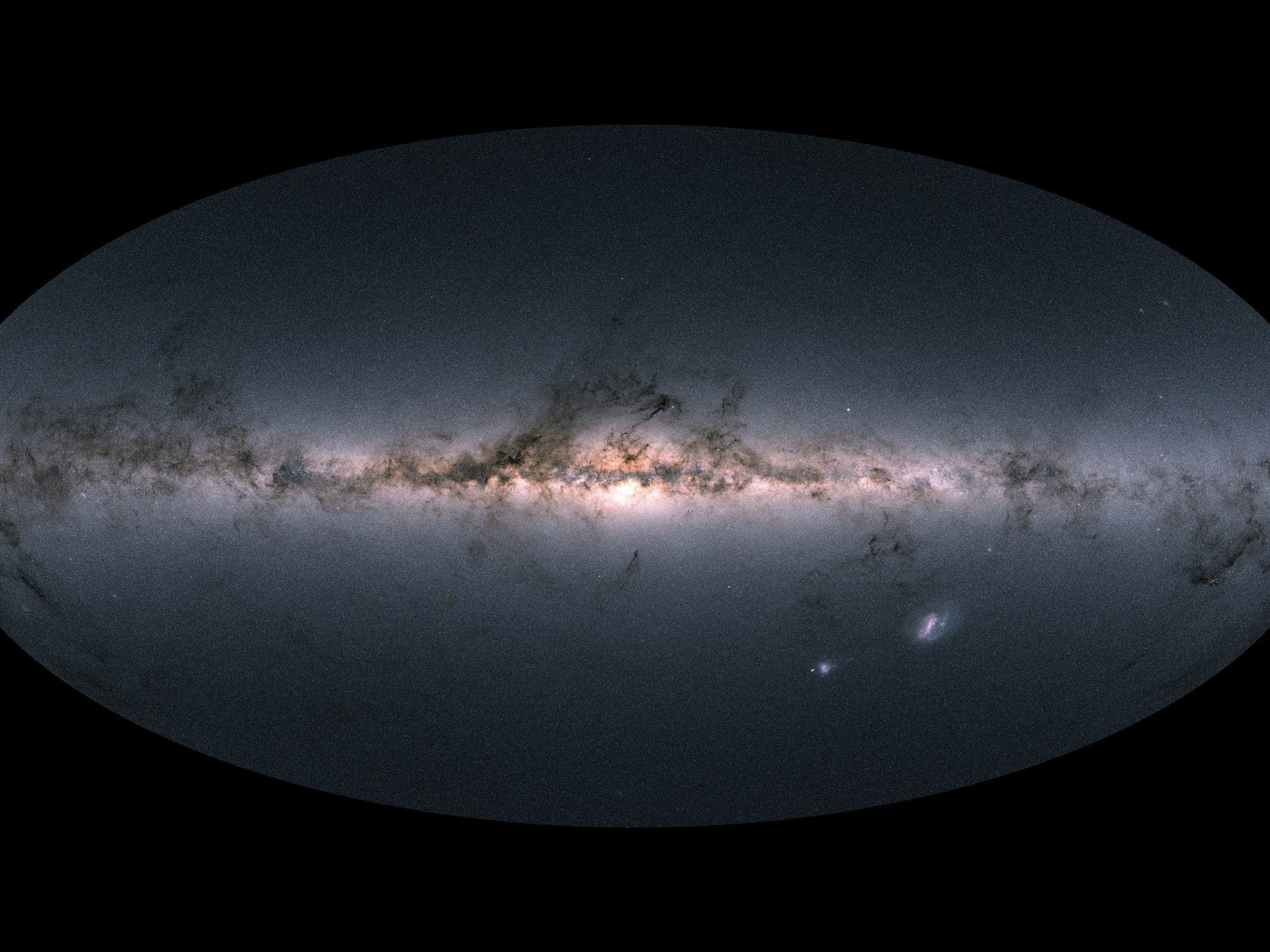

Until recent years, astronomers could only calculate proper motions laboriously by comparing the stars’ positions now with measurements taken decades or centuries earlier. But a revolutionary spacecraft called Gaia has now put that firmly into the past tense. From its orbit around the Sun, Gaia measures 850 million star positions every day. Since its launch in 2013, Gaia has catalogued 2 billion stars, across half of our Milky Way galaxy.

Gaia has found moving streams of stars in our Milky Way which are the remains of small galaxies that have been consumed by our galaxy. And it’s even measured the proper motions of other galaxies that are orbiting around the Milky Way, out to distances of a million light years and more.

What’s Up

With Midsummer’s Day coming up on 21 June the evenings don’t grow dark until very late, but there are a couple of planets you can spot well before the faintest stars become visible. Brilliant Venus shines in the west after sunset, heading inexorably upwards towards our other neighbour planet, Mars. Venus is currently much the closer of the two worlds, and it shines over 200 times more brightly than the Red Planet.

On 13 June, Venus passes just above Praesepe. This lovely cluster, 610 light years away, contains around a thousand stars swarming like a cloud of bees. Visible to the naked eye as faint glowing patch of light, its Latin name means “the manger.” The ancient Chinese, on the other hand, knew Praesepe as “the exhalation from piled up corpses.”

Low on the southern horizon lies the bright red star Antares, marking the heart of the celestial scorpion, Scorpius. Three stars to the upper right of Antares mark the scorpion’s head and forelimbs, while its long tail curves down below the horizon.

A large loop of faint stars above Antares traces the outline of Ophiuchus, the Serpent-Bearer, with stars to either side depicting the giant snake he’s carrying. And higher up still is the constellation Hercules, his dim stars a poor reflection as his mythological ranking as the greatest of the Greek heroes.

The Moon passes Saturn in the early hours of 10 June and Jupiter just before dawn on 14 June. The crescent Moon forms a lovely sight next to Venus and Mars on 21 and 22 June.

Diary

10 June, 8.31 pm: Last Quarter Moon near Saturn

13 June: Venus very near Praesepe

14 June (am): Moon very near Jupiter

18 June 5.37 am: New Moon

21 June 3.57 pm: Summer Solstice; Moon near Venus and Mars

22 June: Moon near Venus, Mars and Regulus

23 June: Moon near Regulus

26 June, 8.50 am: First Quarter Moon

27 June: Moon very near Spica

30 June: Moon near Antares

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2023‘ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments