Stargazing in September: King of the rings

A lone sentinel shines in the southern sky this month – Saturn, writes Nigel Henbest

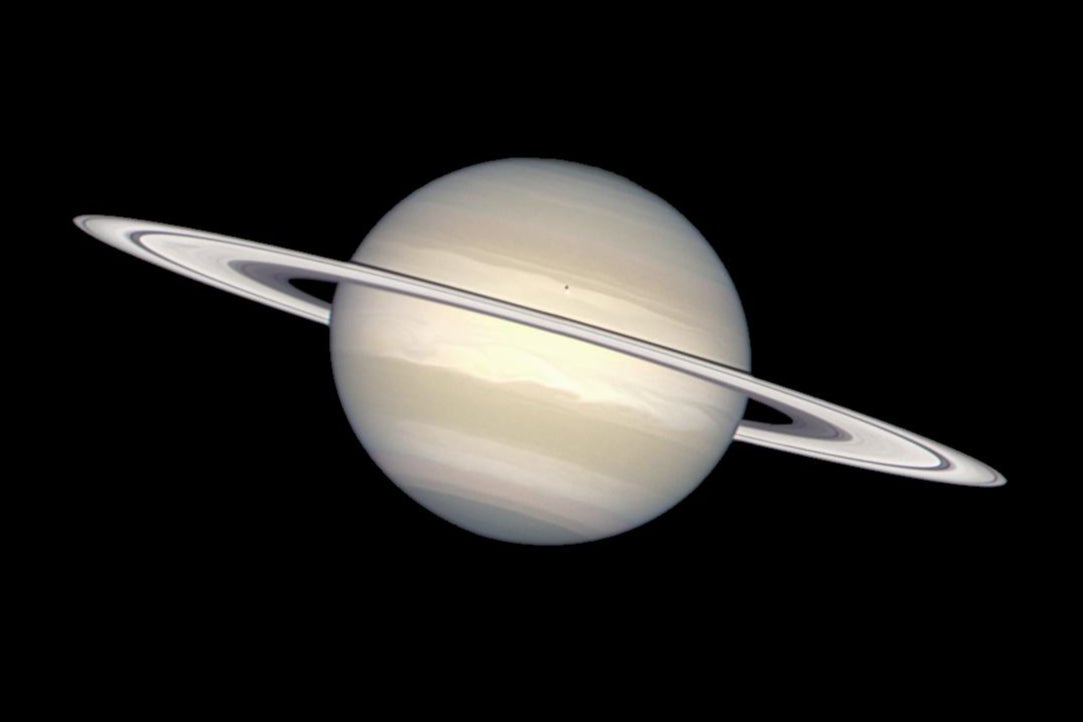

A lone sentinel shines in the southern sky this month, a bright steady beacon in a region of dim twinkling stars. Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is at its closest to the Earth – and brightest – on 8 September. And it is a celestial masterpiece, whether you check out Saturn online or, even better, grab a telescope and view it for yourself.

Saturn is the second largest planet in our Solar System, outranked only by Jupiter. It’s 95 times heavier than the Earth, but because the planet is mainly made of gas, Saturn’s density is so low that it would float on water – if you could find an ocean big enough!

Powerful winds, roaring up to 1,800kph, rip through Saturn’s lower atmosphere, though most of this action is hidden from us by a high-altitude haze of ammonia crystals that leaves the planet looking like a bland creamy yellow globe. Roughly every 30 years, at its "summer solstice" when the planet’s northern hemisphere is most inclined towards the Sun, Saturn’s true tempestuousness erupts in giant white storms that can stretch around the planet.

Surrounding Saturn is the largest entourage of moons in the Solar System, the total currently standing at 146. Most of these moons are only a few kilometres across, but the largest – Titan – is among the most massive moons known, with an atmosphere even thicker than the Earth’s. And icy Enceladus has a subsurface ocean where conditions may be right for life to evolve.

When you first look at Saturn, though, it’s not the planet’s globe or its moons that catch your eye, but the magnificent set of rings girdling the planet. Saturn is not the only ringworld: Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune all have faint rings. But Saturn’s rings are by far the brightest and biggest, wide enough to stretch most of the way from the Earth to the Moon. For all their enormous width, though, the rings are paper-thin – no more than 20 metres thick.

Made from chunks of ice ranging in size from snowflakes to icebergs, the rings are probably the residue of an icy moon that was either broken up by Saturn’s gravity or smashed to pieces by the impact of a comet.

Three spacecraft – two Voyagers and Cassini – have viewed the rings at close quarters, and discovered they are composed of hundreds of thousands of concentric narrow ringlets: in close-up, Saturn’s bright look like the grooves in a vinyl record.

And wider dark gaps separate the various rings. The seventeenth-century Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Cassini discovered the broadest dark gap: we now know it’s a region swept clear of icy particles by the regularly recurring gravitational pull of a moon called Mimas. The Cassini Division separates the bright B-ring from the outer A-ring.

Near the edge of the A-ring lies the Encke Gap. It’s swept clear by a small moonlet called Pan which is actually orbiting within the ring system and pushing the ring particles out its way like a snowplough.

While the detailed views of Saturn’s rings from the Cassini spacecraft (which orbited Saturn in 2004-2017) are impressive, nothing prepares you for your first glance at the planet through a backyard telescope. It looks truly three-dimensional, like a finely crafted model suspended in front of your instrument.

Through a telescope you can see that the rings’ appearance changes from year to year, because our perspective on them alters as Saturn follows its orbit around the Sun. Several years ago, the rings appeared wide open. But now we’re viewing them at a shallow angle, and the rings are foreshortened.

Although the overall effect is less spectacular, this perspective actually makes it easier to spot the dark Cassini Division and the Encke Gap at the outer extremities of the rings. Watch over the next few months, and you’ll see the rings growing ever narrower. Next March, the Earth passes though the plane of the rings – though unfortunately we won’t be able to actually see this rare event as Saturn will be too close to the Sun. When Saturn returns to our night sky, later in 2025, we’ll be seeing the other side of its glorious rings.

What’s Up

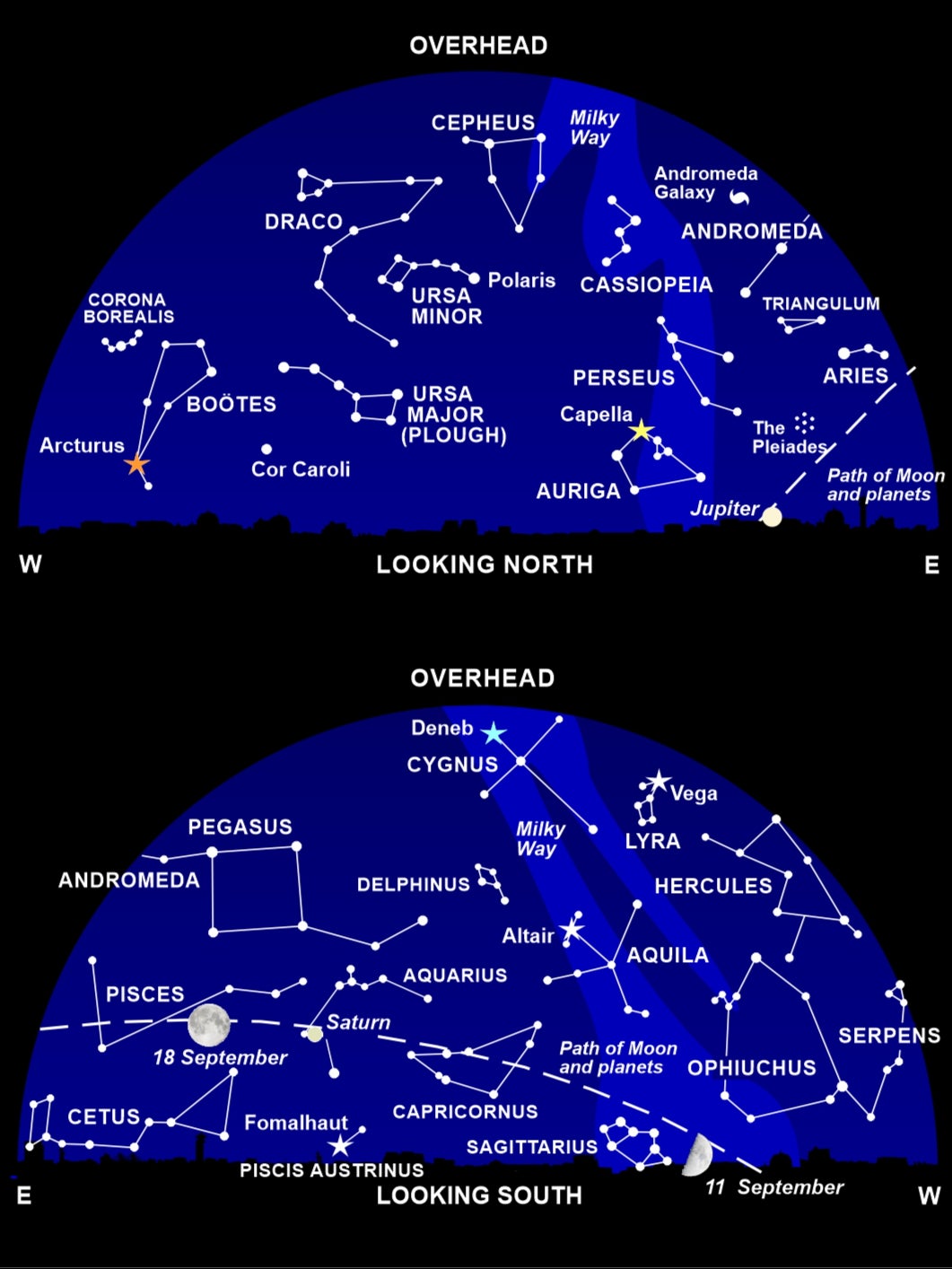

Brilliant Venus is low in the western sky after sunset, forming a lovely sight with the crescent Moon on 5 September. The Evening Star is rising ever higher in the sky, and it will be a stunning sight for months to come.

After Venus has set, around 8 pm, the brightest planet is Saturn, over in the south (see main story). Above Saturn, four stars mark the corners of the Square of Pegasus, a winged horse in Greek mythology. A line of stars to its upper left depicts the princess Andromeda, while below you’ll find the small constellation of Aries (the ram) and two sprawling lines of stars representing Pisces - two fishes with their tails tied by a cord.

Jupiter rises around 10.30pm in the northeast, followed by rather fainter Mars, Both lie in the constellation Taurus (the bull), near its leading star Aldebaran and the lovely star cluster of the Pleiades – the Seven Sisters.

During the first two weeks of September, Mercury is putting on its best morning show of the year, low in the east before dawn.

Keep a close eye on the Full Moon on the night of 17-18 September. It’s a supermoon: nearer, bigger and brighter than the average Full Moon, but not quite as spectacular as the supermoon next month. And it also suffers a lunar eclipse, visible from Europe (including the UK and Ireland), Africa and the Americas. But don’t hold your breath, as only 8 per cent of the Moon is obscured by the Earth’s shadow at maximum eclipse (3.44am BST).

Towards the end of month, early risers have a chance to spot a comet low in the east around 6.30am. Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS has swung in from deep space, and passes closest to the Sun on 27 September. If it survives this fiery encounter, the comet may become an astounding sight in the evening sky in October – I’ll be updating you on this celestial visitor in next month’s Stargazing column!

5 September: Moon near Venus; Mercury at greatest elongation west

8 September: Saturn at opposition

10 September: Moon near Antares

11 September, 7.05am: First Quarter Moon

16 September: Moon near Saturn

17 September: Moon near Saturn

18 September, 3.34am: Full Moon; supermoon; partial lunar eclipse

22 September, 1.43pm: Autumn equinox

23 September: Moon near Jupiter

24 September, 7.49pm: Last Quarter Moon

27 September: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS at perihelion

Nigel Henbest’s ‘Stargazing 2025’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments