Stargazing in August: The magical sight of meteors

The sky is putting on an action-packed show this month, writes Nigel Henbest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a portent sent from heaven. In the summer of AD 36, Chinese Emperor Guangwu was on a campaign to re-unify the Han empire, when his astronomers reported a strange sight: over a hundred bright meteors flashing across every part of the night sky.

In Chinese astrology the sky was the mirror of the Earth, with the constellations representing different regions in and around China, and shooting stars denoting change. Meteors intersecting so many constellations were a sure sign that major changes were coming throughout the region. By the end of the year, Emperor Guangwu had indeed conquered his rebellious neighbours, and succeeded in reuniting China under the Eastern Han dynasty.

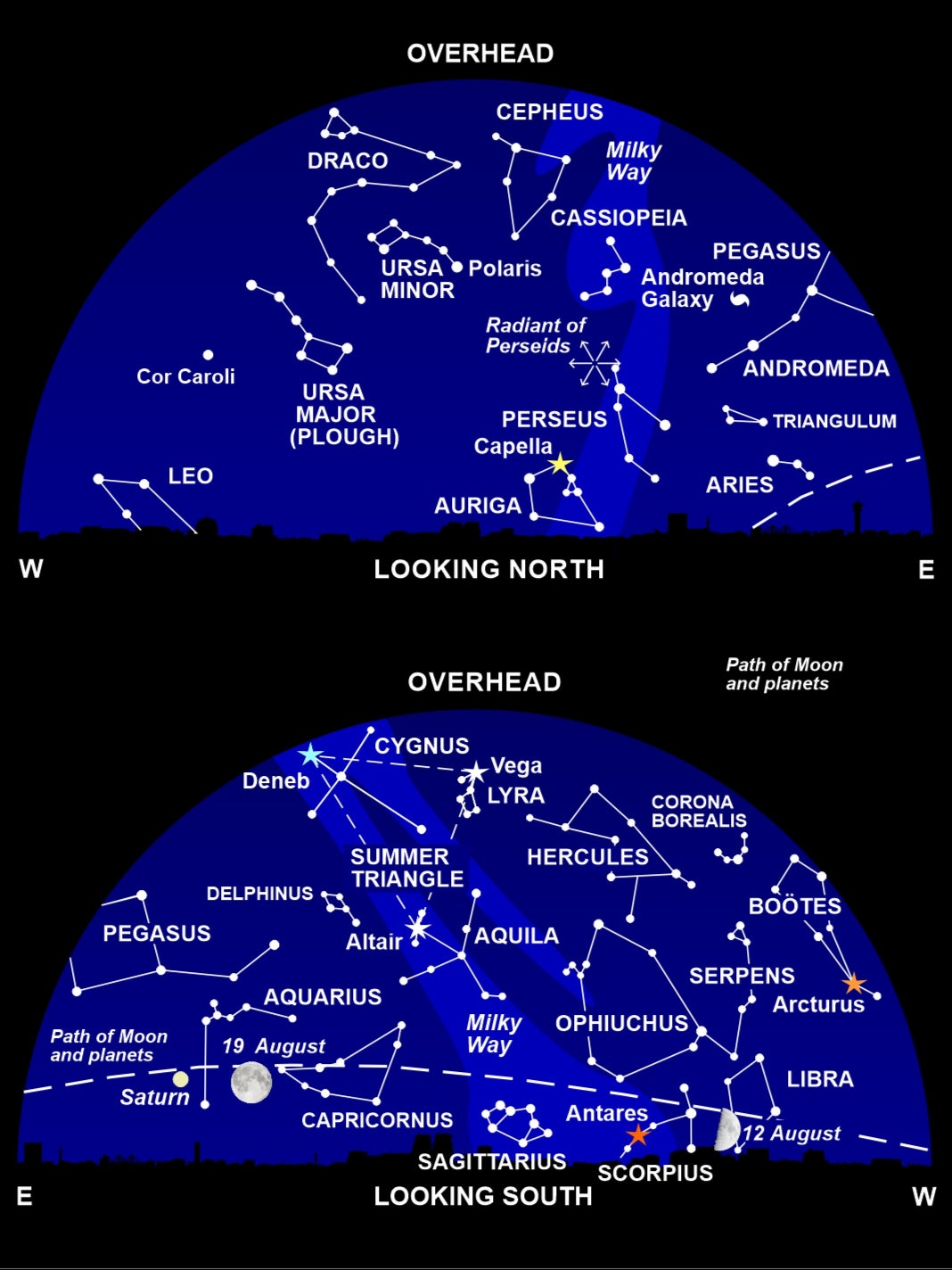

This month, we’re treated to a repeat performance. On the night of 12-13 August, stay up for a few hours and you’ll be treated to dozens of shooting stars spraying out from the constellation Perseus across most of the sky.

The display in AD 36 is the first reported occurrence of the Perseid meteor shower, and it was probably unusually intense to have attracted such attention. But these shooting stars appear every summer around this time: when people ask me why they see more meteors when they’re on vacation, I reply: ‘so you always go on holiday in mid-August!’

Every year around this date, the Earth crashes through a stream of debris scattered along the orbit of Comet Swift-Tuttle. Particles of dust about the size and texture of instant coffee granules smash into the air above our heads – at 210,000 km per hour – and burn up as shooting stars. Although the dust particles enter the atmosphere on parallel paths, perspective makes them seem to diverge from a radiant in Perseus (marked on the star chart).

To see the Perseids at their best, choose a site that’s away from artificial lights and is clear of buildings and trees for the widest possible view (though the shooting stars fan out from Perseus, they can appear anywhere in the sky). Wait until the Moon sets - around 10.45 pm – so it’s really dark and you can spot the faintest meteors. Best of all, observe after midnight when the Earth is rotating into the stream of debris: the planet is then sweeping up more debris and the particles are hitting the atmosphere faster, harder and brighter.

The Perseid are an annual fixture, but we have a much longer wait to see the comet that spawned them. Named after the two American astronomers who discovered it in 1862 – Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle – Comet Swift-Tuttle follows an elongated orbit that takes it around the Sun in 133 years. It was last in our neck of the woods in 1992, though it was then only visible through binoculars or a telescope.

It will be a different story on Comet Swift-Tuttle’s next return. In 2126, it will pass just 23 million kilometres from the Earth and should be as spectacular a sight as in our skies as Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997.

In 3044, Comet Swift-Tuttle is predicted to pass just 1.5 million km from our planet. It’s possible – though, admittedly, unlikely – that the comet might just impact the Earth. The effect would be catastrophic.

The icy nucleus of Swift-Tuttle is the largest object we know that could hit the Earth head-on. Some 26 km across, it’s 200 times more massive than the nucleus of Halley’s Comet, and twice the size of the comet that wiped out the dinosaurs. Given the incredible speed of Swift-Tuttle, it would cause far worse devastation than the impact 66 million years ago. And this time, it’s not dinosaurs that are in the firing line, but us.

So when you watch the magical sight of a Perseid meteor, and make a wish, be thankful that it’s just a chip off the old block that’s impacting our planet, and not the comet itself!

What’s Up

The sky is putting on an action-packed show this month, with meteors, the Moon, several planets and the Seven Sisters taking on starring roles – although unfortunately some of the acts are only visible in the wee small hours.

First up, the crescent Moon passes just to the right of Venus after sunset on 5 August. You’ll need a clear horizon to the west, and preferably a pair of binoculars, to catch this conjunction of the two brightest objects in the sky (after the Sun).

On the night of 12-13 August, watch out for shooting stars lighting up the night sky (see main story). The next evening the Moon passes near the red giant star Antares, low in the south.

Early birds will have noticed brilliant Jupiter in the early morning sky, with Mars to its upper right: the orange star Aldebaran lies below, with the sparkling Pleiades to the upper right. Speedy Mars is heading leftwards across the heavens, and on the morning of 15 August it skims just half a moon’s-width above Jupiter. Grab binoculars to view the Red Planet in the same field of view as the Solar System’s giant world, along with its four largest moons.

On the night of 20-21 August, we’re in for a rare astronomical sight. The bright ‘star’ you’ll see near the Moon during the evening is the planet Saturn. Stay up until the early hours, and you will witness the Moon move right in front of the ringworld between 4.28 and 5.21am (the precise time depends on your location, so start watching around 4.20am).

And at a similar time on the morning of 26 August, the Moon moves in front of the Pleiades star cluster – popularly known as the Seven Sisters – and hides some of its stars.

4 August, 12.13pm: New Moon

5 August: Crescent Moon near Venus

9/10 August: Moon near Spica

12 August, 4.18pm: First Quarter Moon: maximum of Perseid meteor shower

13 August: Moon near Antares

15 August, early hours: Close conjunction of Mars and Jupiter

19 August, 7.25pm: Full Moon

20 August: Moon near Saturn

21 August, 4.28-5.21 am: Moon occults Saturn

26 August, 4.50-5.30 am: Moon occults the Pleiades

26 August, 10.26 am: Last Quarter Moon

31 August, early hours: Moon near Jupiter

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments