Stargazing June: Mighty Jupiter reigns supreme

Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest show you how to spot this giant world through the telescope

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mighty Jupiter reigns over the southern skies this month. It’s the brightest object in the heavens in June – apart from the sun and moon, of course, and Venus rising just before the sun – and on 12 June, it makes its closest approach to Earth (a “mere” 641 million kilometres away). This cloudy world, swathed in deep layers of gas, is superb at reflecting sunlight.

Measuring 143,000km across, Jupiter is the biggest planet in the solar system; so huge that it could swallow 1,300 Earths. As befits its colossal status, Jupiter is also the ruler of a huge retinue of underlings – in this case, moons (79 at the last count).

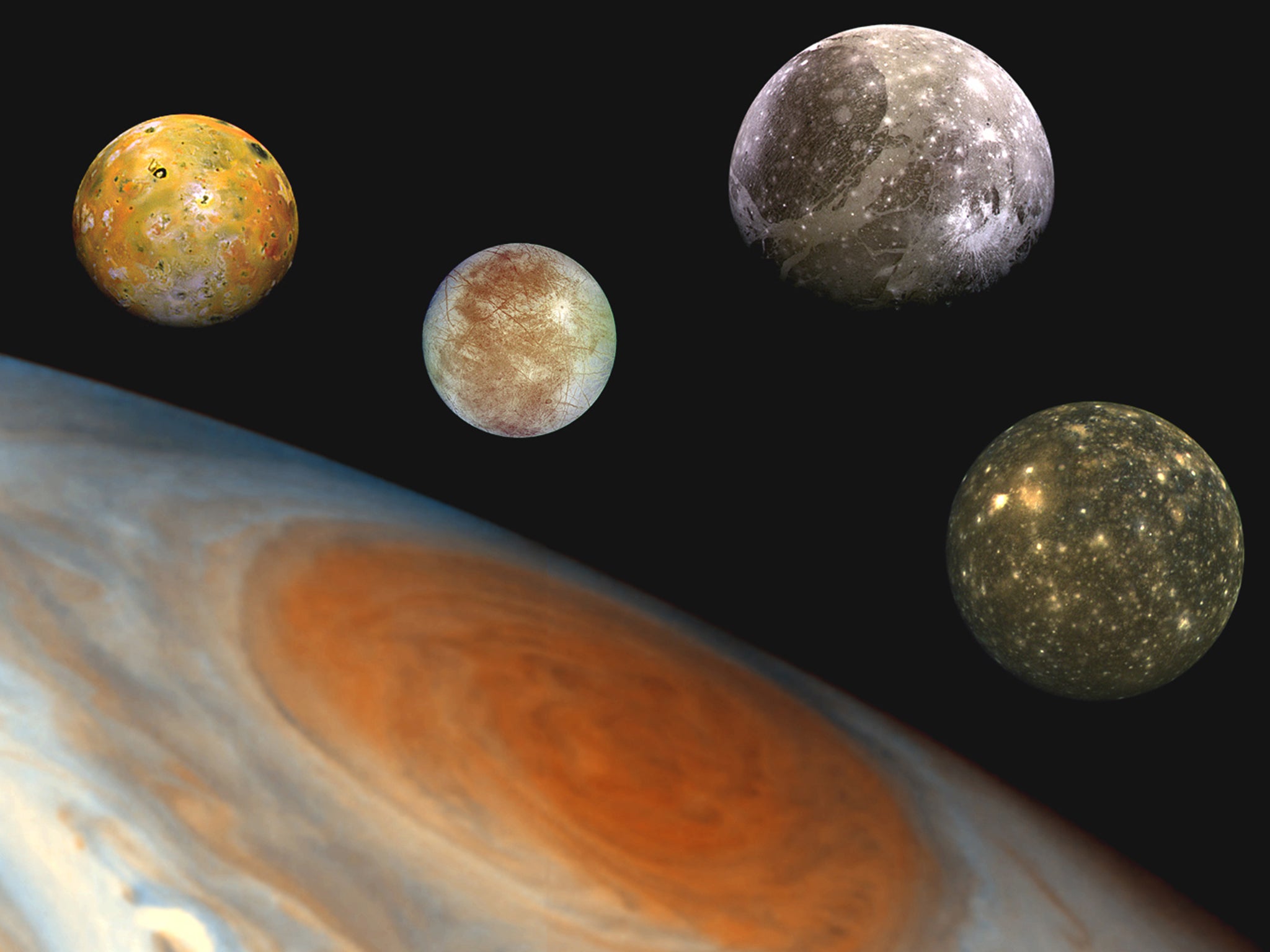

If you can, take a look at the giant world through binoculars or a small telescope. You’ll easily see four little “stars” attending it (very keen-sighted people have reported that they’ve spotted them with the unaided eye). These are the four largest of Jupiter’s enormous family of natural satellites..

Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto are known as the “Galilean” moons – because Galileo famously sketched their positions from night to night, observing them through his tiny telescope. It convinced him if that smaller objects (like moons) could orbit larger bodies (such as Jupiter), then it was natural that the planets orbited the much bigger sun. The bold idea got him into a spot of bother with the church, which believed in the sanctity of a central Earth in the cosmos – and was one of the factors that led to his eventual house-arrest.

But do they deserve to be called the “Galilean” moons? In the early 1600s, Europe was awash with a new invention called the telescope. Designed by a Dutch optician called Hans Lippershey (or Lipperhey), it brought distant objects closer. Ideal for military use, it could also be used as a toy – or, in this case, bringing the heavens nearer.

The German astronomer Simon Marius was among the first to point his (homemade) telescope at the sky, in around 1609. Though accounts are uncertain (because Galileo and Marius were going by different calendars in use at the time), Marius almost certainly observed the moons of Jupiter a month before Galileo. And he gave them their names: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, after Jupiter’s most famous lovers.

As he wrote: “Io, Europa, Ganimedes puer, atque Calisto lascivo nimium perplacure lovi.” If your school Latin isn’t up to it, this translates as: “Io, Europa, the boy Ganymede and Callisto greatly pleased lustful Jupiter.”

None of this pleased irascible Galileo, whose paper on Jupiter’s four biggest moons had come out before that of Marius. Galileo (unfairly) accused Marius of plagiarism, and called him “a poisonous reptile”.

Back to the moons. Io is first off the mark, circling Jupiter in just 1.8 days. At 3,640km across (a little bigger than our 3,474km moon), it looks like a cosmic pizza, with dollops of tomato, mozzarella and olives heaped over it. The reason? Io is the most volcanically active object in the solar system, and its surface reflects the moon’s internal turmoil. Jupiter’s powerful gravity is pummelling this helpless little moon, and it erupts continuously. Io’s huge volcanoes shoot massive plumes of sulphur dioxide 300km into space.

Next out is smaller Europa (3,100km across), which circles Jupiter in 3.5 days. If ever two moons could be more different, it’s the case here. While Io is made of fire, Europa is an ice world. Its brilliantly white surface is smoother than a billiard ball – and under it may lurk a deep ocean. This could be a habitat for primitive marine life.

Orbiting Jupiter in 7.2 days, Ganymede follows. With a diameter of 5,268km, it’s the largest moon in the solar system – bigger than the planet Mercury. Made of ice, Ganymede is heavily cratered from bombardment in the past. But its surface shows a complex system of ridges and grooves – signs of more recent activity.

The outermost “big” moon in Callisto, a twin of Ganymede, circling the giant planet in 16.7 days. You won’t see anything flat on Callisto: its icy surface is covered in impact craters. The record-holder is Valhalla – a whopping 300km across.

Listen out for more about these motley moons as the 2020s unfold. Europe will be sending its Juice (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) space probe to explore Ganymede, Callisto and Europa; the latter will also be the target of Nasa’s Europa Clipper. Anyone for a chilly swim?

What’s up

With the summer solstice on 21 June, this month sees the shortest nights of the year – but there’s still plenty of action up in the sky after the sun has set.

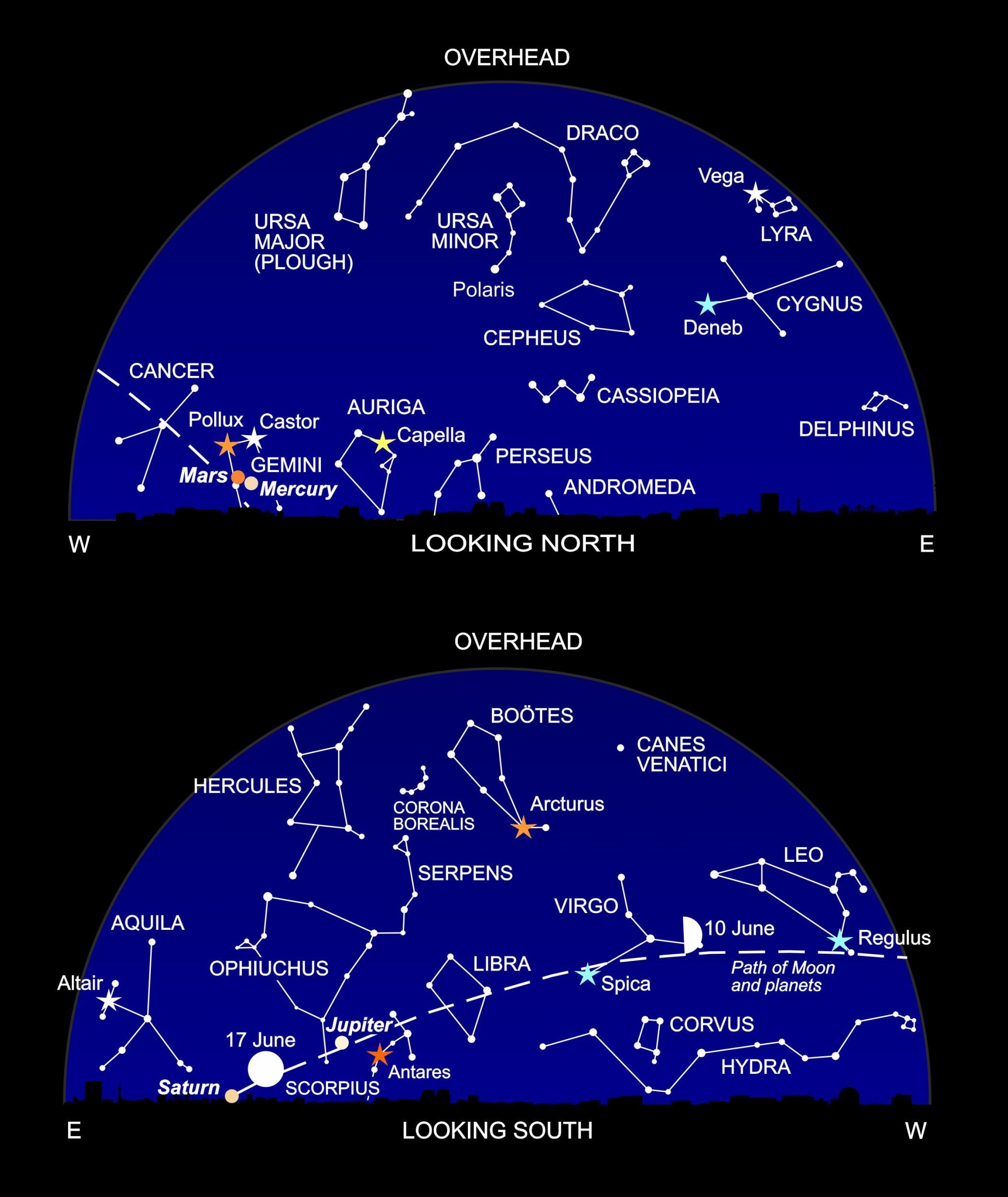

Glorious Jupiter is on view all night long, low in the south: on 16 June, the moon lies right next to the giant planet. The reddish star to the right of Jupiter is Antares, marking the heart of the celestial scorpion, Scorpius. To the left of Jupiter – and rising about 11 pm – is fainter Saturn.

Above the solar system’s two giant worlds sprawl two huge dim constellations, both depicting ancient mythical giants. Immediately over Jupiter, a large faint ring of stars traces the outline of Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer. In myth, he’d seen a snake brought back to life by a wonderful herb – and achieved celebrity status by using this magic balm to revive a dead prince. Now in the sky, he still clutches his pet snake (Serpens) whose head stretches up towards brilliant Arcturus.

Looking higher, an hourglass pattern of stars depicts the body of the mighty hero Hercules. Oddly enough, ancient drawings of the constellation show him upside-down, his head dangling downwards towards Ophiuchus.

This month provides your best chance this year to spot Mercury, the tiny innermost planet that never strays far from the sun. Look towards the northwest horizon around 10 o’clock, and the brightest “star” you’ll see is elusive Mercury.

Around the middle of June, you’ll find the twin stars of Gemini – Castor and Pollux – above Mercury, and Mars to its left. Though the red planet is bigger than Mercury, it’s currently much further away and appears three times fainter. Mercury passes extremely close to Mars on the 18 June – take a look in binoculars or a small telescope to see the solar system’s two smallest planets together.

Finally, if you’re up early, you may catch the brilliant Venus rising in the northeast before the sun.

Diary

8 June Moon near Regulus

10 June, 6.59am Moon at First Quarter; Jupiter at opposition

12 June Jupiter closest to Earth; moon near Spica

15 June Moon near Jupiter and Antares

16 June Moon very near Jupiter

17 June, 9.31am Full moon

18 June Mercury very close to Mars; moon near Saturn

19 June Moon near Saturn (am)

21 June, 4.54pm Summer solstice

23 June Mercury at greatest eastern elongation

25 June, 10.46am Moon at last quarter

Fully illustrated, ‘The Universe Explained’ (Firefly, £16.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest is packed with 185 of the questions that people ask about the cosmos

And Heather and Nigel’s ‘Philip’s 2019 Stargazing’ (Philip’s £6.99) reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments