Stargazing May: Your chance to see an iconic celestial visitor

Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest show you how to see Halley’s Comet this month

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Missed Halley’s Comet in 1985-86? Well, now’s your chance catch a glimpse of the occasional celestial visitor – albeit only bits of it.

Set an alarm for the wee small hours of 6 May (yes, we know it’s bank holiday) and – if it’s clear – you should be rewarded by the sight of shooting stars whizzing across the sky from 3am till dawn. These are coffee grain-sized particles of cosmic dust from Comet Halley, plunging into our atmosphere at speeds of around 155,000mph and burning up in a blaze of glory in the sky some 80km (50 miles) upwards.

Why the early start? It’s because the stream of dust is sneaking up on us from an inconvenient direction. As the Earth ploughs through the debris from the dirty comet (imagine Halley’s Comet as a leaky wheelbarrow), perspective makes the meteors appear to emanate from one point in the sky – the radiant – just as the parallel lanes of a motorway appear to diverge from a distant point on the horizon. And it happens that this particular radiant lies in the constellation of Aquarius, which doesn’t rise until close to dawn. The shooting stars appear to fly outwards from the constellation’s brightest star Eta Aquarii, giving the shower its name: the Eta Aquarids.

If you see a meteor and can trace its path back to that direction (low in the east), you’ve spotted your chunk of Halley. Expect to see a brief streak across the sky, lasting no more than seconds. From an ideal location, you might catch 40 meteors per hour, but that’s a generous estimate and you’ll need really dark and transparent skies. But the moon’s light doesn’t interfere this year, which is why this particular shower is worth catching.

Meteor showers are notoriously unpredictable. The Leonids – a November shower – have been known to produce storms of shooting stars, when thousands of meteors rain down from the sky. Even the Eta Aquarids have given us surprises. In 2013, they yielded rates of over 130 meteors per hour. The problem is that the dust shed by the comet was dumped hundreds or even thousands of years ago – and it’s difficult to know in advance if the Earth’s encounter is destined to be with a dense clump, or a sparse one.

Halley’s Comet is still happily tramping our solar system, just a few years from reaching the furthest point in its 76-year orbit. Today, anyone who discovers a comet has it named after them (three names are allowed) – but Edmond Halley, the second astronomer royal, didn’t actually discover his comet.

He first saw it on his honeymoon (in Islington!) in 1582. Armed with the figures calculated by his reclusive friend Isaac Newton – who was working on his theory of gravity at the time – Halley calculated that the comets seen in 1531 and 1607 were actually the same object returning to the sun. Boldly, Halley predicted that it would return in 1758, after his death – and he was spot-on. Rightly, the comet was named in Halley’s honour.

His comet – a dirty cosmic snowball some 15km long, which puts on a light-show when it comes close to the sun – has been a regular fixture since at least 240BCE. It is chiefly famous for its appearance in 1066, as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. The comet hovered ominously in the sky as William, duke of Normandy decisively defeated the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings.

Halley’s Comet is due back for its next appearance in 2061, but don’t hold your breath. If you were disappointed by its 1985-86 performance, this is going to be almost as bad.

Our advice? Try to hang on until 2134, when the comet will be close to the Earth, and a spectacular sight in our skies.

What’s up

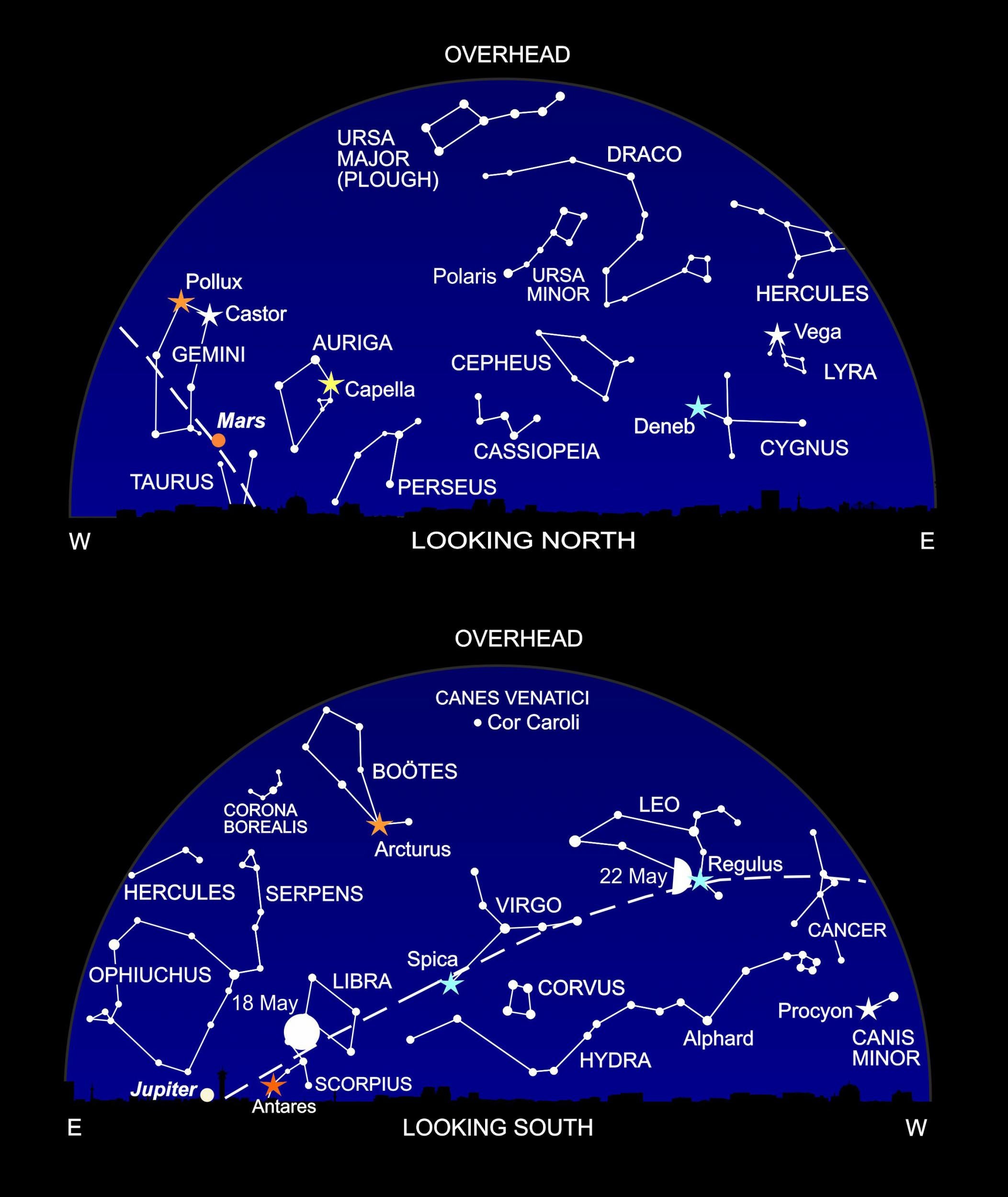

Shining brilliantly high in the south is Arcturus, the fourth brightest star in the sky (and the second most brilliant visible from Britain, after winter’s glorious Sirius). A star reaching the end of its life, Arcturus has swollen up to become an orange giant, 25 times wider than the sun.

It’s the main ornament of the constellation Boötes (the Herdsman) which rises up from Arcturus in a distinctive kite-shape. To the left, a curve of faint stars makes up Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown), while an isolated star to the right – Cor Caroli – is the only prominent star in the constellation of Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs). Its name means “heart of Charles”, supposedly because it appeared particularly bright when King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660.

To the west, after sunset, you can catch Mars low down below Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini. There’s a lovely sight on 7 May, when the crescent moon hangs close to the Red Planet.

Over in the southeast, brilliant Jupiter is rising at around 11 pm, followed a couple of hours later by Saturn. And in the early hours of the morning – maybe on a meteor watch – you may catch iridescent Venus rising in the east just before the sun.

Diary

4 May, 11.45pm New moon

6 May Maximum of Eta Aquarid meteor shower (am); moon near Aldebaran

7 May Maximum of Eta Aquarid meteor shower (am); moon near Mars

10 May Moon near Praesepe

12 May, 2.12am Moon at first quarter; moon near Regulus

15 May Moon near Spica

16 May Moon near Spica

18 May, 10.11pm Full moon

19 May Moon near Jupiter and Antares

20 May Moon near Jupiter

21 May Moon near Jupiter (am)

23 May Moon near Saturn (am)

26 May, 5.33pm Moon at last quarter

‘The Universe Explained’ (Firefly, £16.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest is packed with 185 of the questions that people ask about the cosmos. And their guide ‘Philip’s 2019 Stargazing’ (Philip’s £6.99) reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments