Astronomers decode why our Solar System is shaped like a croissant

Shape of the bubble around the Sun and the planets determines how cosmic radiation gets into the Solar System

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hydrogen particles slamming into the Solar System from outside could be playing a crucial role in determining the shape of the protective bubble around our Sun and its planets, according to a new study.

Astronomers say this bubble, known as the heliosphere, protects planets within our solar system from intense galactic radiation such as those from supernovas – the final explosions of dying stars throughout the universe.

If not for this protective layer, scientists say there could be increased risk to life on Earth and also for astronauts in space due to the powerful cosmic radiation.

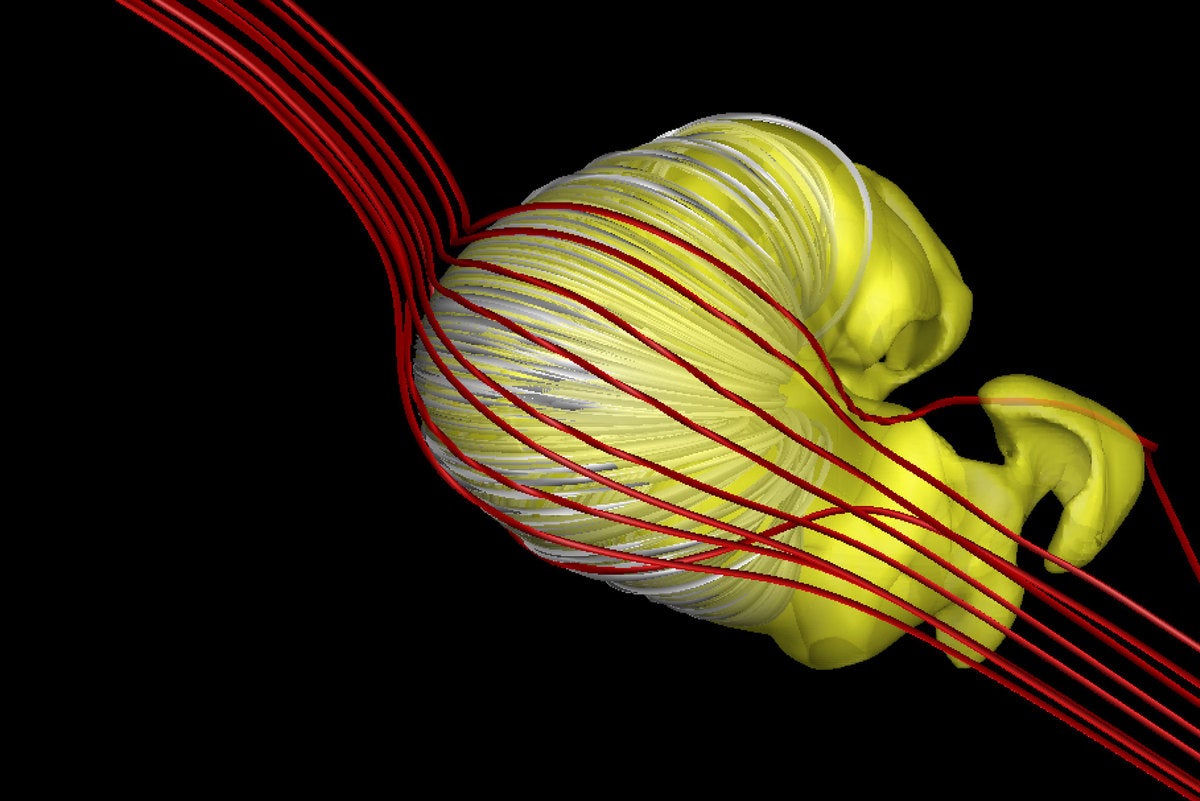

While researchers previously held that this magnetic bubble around the Solar System is shaped like a comet, with a rounded leading edge and a long trail behind it, data from a range of different Nasa missions last year suggested it is more like a deflated croissant.

The new study, published in The Astrophysical Journal on Friday, found that neutral hydrogen particles – so-called because they have equal amounts of positive and negative charge – determine the shape of the heliosphere.

“The bubble that surrounds us, produced by the sun, offers protection from galactic cosmic rays, and the shape of it can affect how those rays get into the heliosphere,” study co-author James Drake, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland, said in a statement.

“There’s lots of theories, but of course, the way that galactic cosmic rays can get in can be impacted by the structure of the heliosphere – does it have wrinkles and folds and that sort of thing?,” Dr Drake added.

In the study, astronomers analysed twin jets of material streaming from the Sun’s poles whose trajectories are shaped by the interaction of the solar magnetic field with the interstellar magnetic field.

These jet streams, the scientists say, are unstable and curved around by the interstellar magnetic field like the points of a croissant.

“We see these jets projecting as irregular columns, and [astrophysicists] have been wondering for years why these shapes present instabilities,” BU astrophysicist Merav Opher, said.

The scientists found using a computer model that when the neutral hydrogen particles were taken out of the simulation, the jets coming from the sun become “super stable”.

But when they were put back, “things start bending, the centre axis starts wiggling, and that means that something inside the heliospheric jets is becoming very unstable”, Dr Opher said.

This kind of instability could cause disturbances in the solar winds and jets emanating from our sun, the scientists say, and may cause the heliosphere to split its shape into something more like a croissant.

While astrophysicists are yet to actually observe the real shape of the heliosphere, Dr Opher’s model suggests that the neutral hydrogen pelting onto the Solar System would make it impossible for the heliosphere to flow uniformly like a shooting comet.

Dr Drake believes the model “offers the first clear explanation for why the shape of the heliosphere breaks up in the northern and southern areas, which could impact our understanding of how galactic cosmic rays come into Earth and the near-Earth environment.”

“This finding is a really major breakthrough, it’s really set us in a direction of discovering why our model gets its distinct croissant-shaped heliosphere and why other models don’t,” Dr Opher says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments