Records of ancient solar super storms may lay in old tree rings

Tree rings contain records of periods of intense cosmic radiation, according to new research, and could correspond to periods of intense, repeated solar storms

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The violent history of the Sun may be recorded beneath the quiet boughs of Earth’s forests — if scientists can figure out how to interpret it.

Scientists have known for a decade that certain tree rings can record periods when high levels of radiation bombard Earth from space. They also found evidence of highly energetic radiation storms occurring regularly throughout Earth’s history, at least the roughly 6,000 year period that can be sampled through the oldest trees.

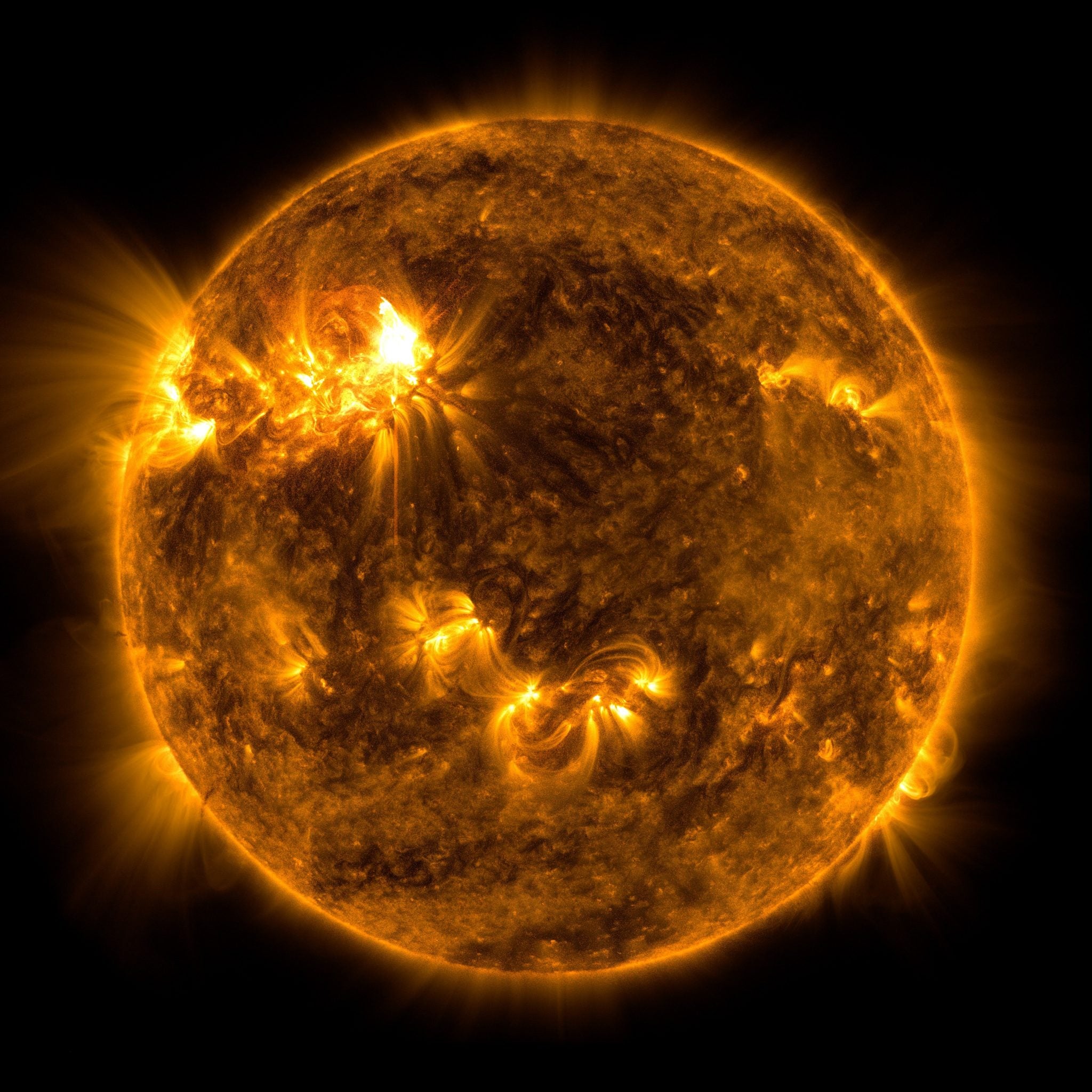

“These huge bursts of cosmic radiation, known as Miyake Events, have occurred approximately once every thousand years but what causes them is unclear,” University of Queensland astrophysicist Benjamin Pope said in a media statement. “The leading theory is that they are huge solar flares.”

Dr Pope is not so sure. He’s the primary researcher behind a new study published Wednesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences that analyzed carbon 14 tree ring data and tried to match it to real world records of celestial events.

It turns out that Miyake events are “not correlated with sunspot activity, and some actually last one or two years,” Dr Pope said. “Rather than a single instantaneous explosion or flare, what we may be looking at is a kind of astrophysical ‘storm’ or outburst.”

The reason tree rings can record levels of cosmic radiation at all is due to the fact that charged particles interact with Earth’s upper atmosphere to create radioactive isotopes of different elements. That is, a version of an element with a different number of neutrons than protons in each atom’s nucleus.

One of the isotopes generated by this process is carbon-14 — it has six protons and eight neutrons instead of the six of each particle found in the non-radioactive and more common carbon-12 — which is readily taken up by plants and trees. Since some trees produce annual growth rings providing a record of the material absorbed by the tree in a given year, scientists can measure the amount of carbon-14 from year to year over the lifespan of a given tree.

It was physicist Fusa Miyake, from whom such events get their name, who first led a study looking at carbon-14 tree ring data and found a spike in carbon-14 levels in 774 CE. Additional spikes have been found in 993 CE, 660 BCE, 5259 BCE, 5410 BCE, and 7176 BCE.

Miyake events correlate to radiation levels far in excess of any contemporary solar storm, and were likely more than an order of magnitude more powerful than the the most intense solar storm on record, the Carrington event of 1859, according to the study authors.

On 1 September, 1859, a solar flare produced a geomagnetic storm — a disturbance in Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere due to the incoming solar radiation — powerful enough to induce overwhelming electric currents in telegraph wires, sparking fires.

“If a Miyake event were to occur today, the sudden and dramatic rise in cosmic radiation could be devastating to the biosphere and technological society,” Dr Pope and his colleagues write in their paper. Follow up research to better understand these phenomena is, he said, in everyone’s interest.

“Based on available data, there’s roughly a one percent chance of seeing another one within the next decade. But we don’t know how to predict it,” Dr Pope said. “These odds are quite alarming, and lay the foundation for further research.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments