The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Can nuclear blasts protect Earth from incoming asteroids? Scientists use X-rays in first successful test

Scientists used the most powerful laboratory source of radiation in the world to mimic the threat

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists may have just created the most efficient way to stop asteroids from obliterating the Earth.

Researchers in New Mexico used Sandia National Laboratory’s Z machine, the most powerful laboratory source of radiation in the world, to mimic how an X-ray pulse could vaporize the surface of an asteroid and deflect it.

While many had theorized that strong X-ray bursts could be an alternative to knocking an incredibly large space rock off its course, that had never been proven or tested.

“We knew we could generate intense X-ray burst using the Z machine. We had already demonstrated that,” physicist Nathan Moore told The Independent on Tuesday. “But, how do you test the deflection of an asteroid in a laboratory?”

At their New Mexico laboratory, Moore and his team miniaturized the experiment, using mock asteroids about the size of a marble. They were radiated with the Z machine’s X-ray pulse.

Their research was published Monday in the journal, Nature Physics.

At just the right moment, the researchers released the silica asteroid into “space” (within their laboratory environment). They had created a vacuum to simulate the environment but, the timing had to be right. They released the tiny asteroid within a billionth of a second before the X-rays started to vaporize their surface.

“And, that sends off an exhaust stream, like the exhaust of a rocket. It pushes the mock asteroid forward,” Moore explained. They measured its acceleration and found that measurement matched their models very well. “And so, the thought is that this could actually work. This was the first experimental demonstration of that concept.”

It’s a concept he believes could be used on very large asteroids, if there’s enough warning. “So, in principle, you could push a dinosaur-killing asteroid out of the way, if you have enough time.”

But those aren’t very common.

Small meteroids, dust, and particles, the remnants of the formation of our solar system, strike Earth every day. It is rare that larger asteroids approach Earth. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) says the next five asteroids to fly by Earth this week will be approximately the sizes of a bus, house, and three airplanes. None of these approaches are close enough to sound off alarms, and all are farther than the average distance between Earth and the moon.

Apophis, a near-Earth object estimated to be about 1,100 feet across, was previously identified as an object of concern. But, any risk that it could impact Earth has been ruled out, as well as the risk of another close approach in 2036. NASA’s calculations don’t show any impact risk for at least the next century, but the threat remains.

Around 25,000 objects the length of a baseball field are believed to exist and could do some damage. The agency said last year that fewer than half have been detected and tracked.

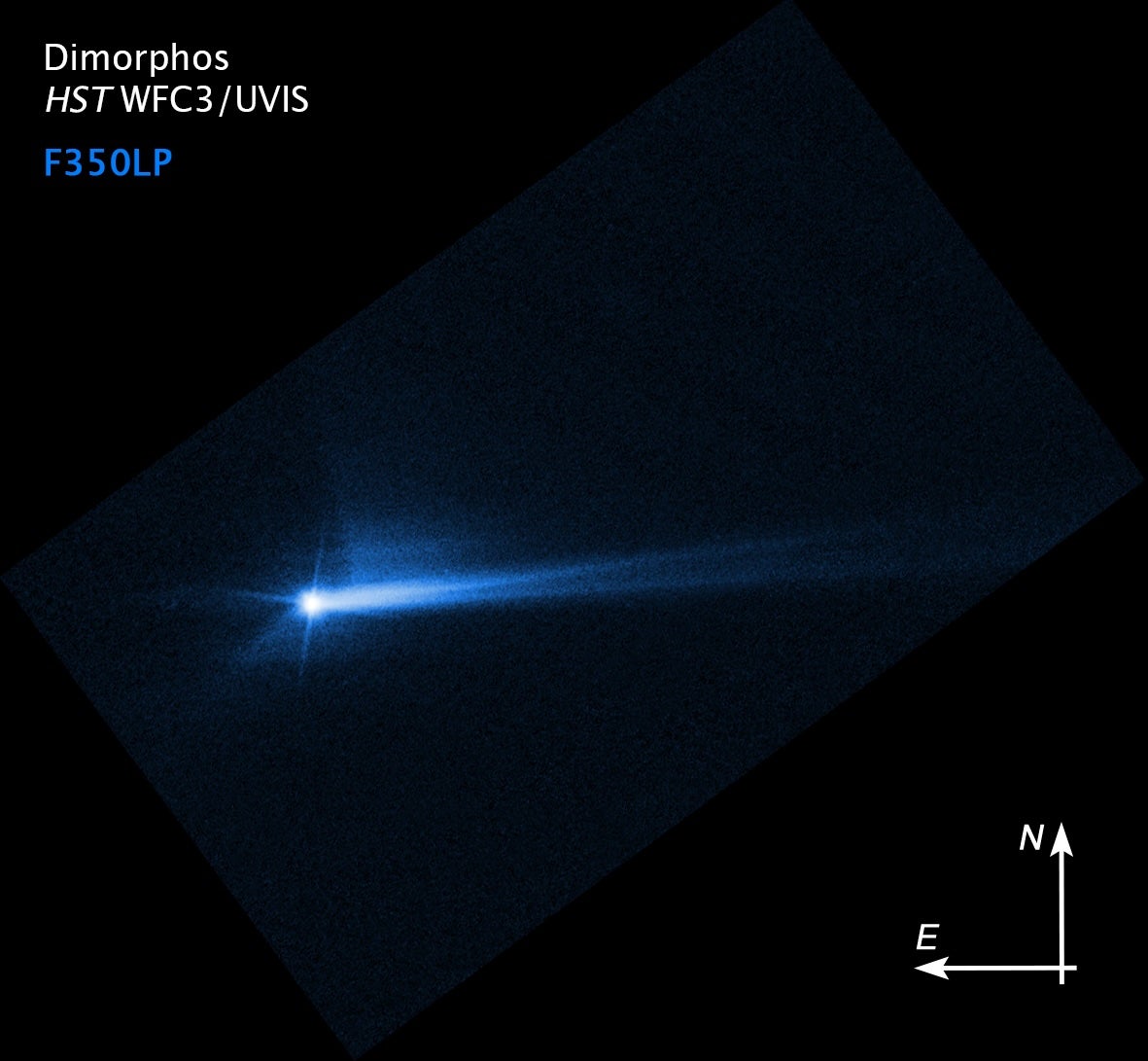

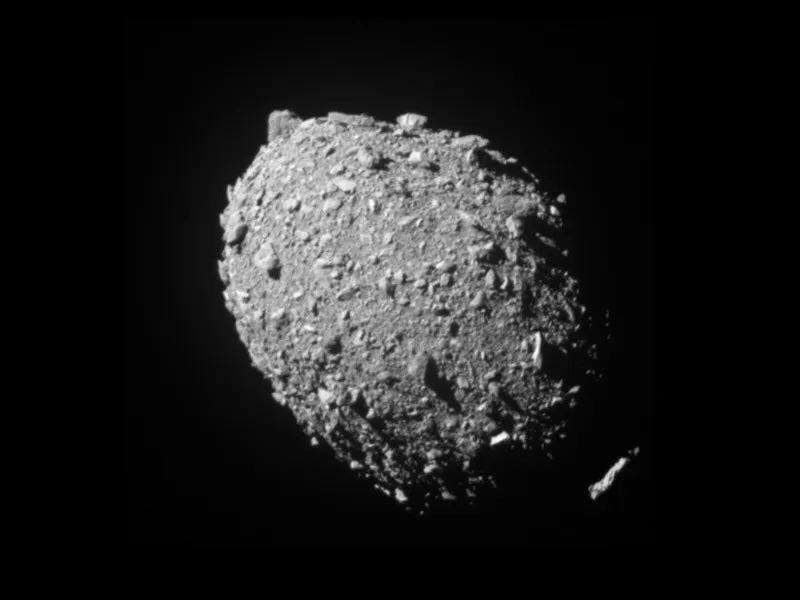

There’s another method to deflect smaller asteroids. The DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission in 2022 demonstrated that hitting an asteroid with a spacecraft could redirect it.

“If the asteroid is very large, multiple kilometers in size or larger, there simply isn’t enough energy available by ramming spacecraft to knock it off course,” said Moore. “You’d have to do something more energetic.”

Still, even small asteroids can be a challenge if there’s not enough warning. And a lot that remains unknown about how asteroids would respond to these methods. Asteroids are composed of many different minerals and some are held together more loosely.

“If you want to win a game of tennis, you have to know all the strokes,” Moore said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments