The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Why stunning Webb telescope images are becoming new normal

You don’t need to wait for Nasa to reveal more Webb photos — anyone can access raw data space telescope transmits to Earth every day

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As an astronomer with the Cosmic Dawn Center in the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Gabriel Brammer normally studies very distant galaxies so faint they show only as red dots for even the most powerful of telescopes.

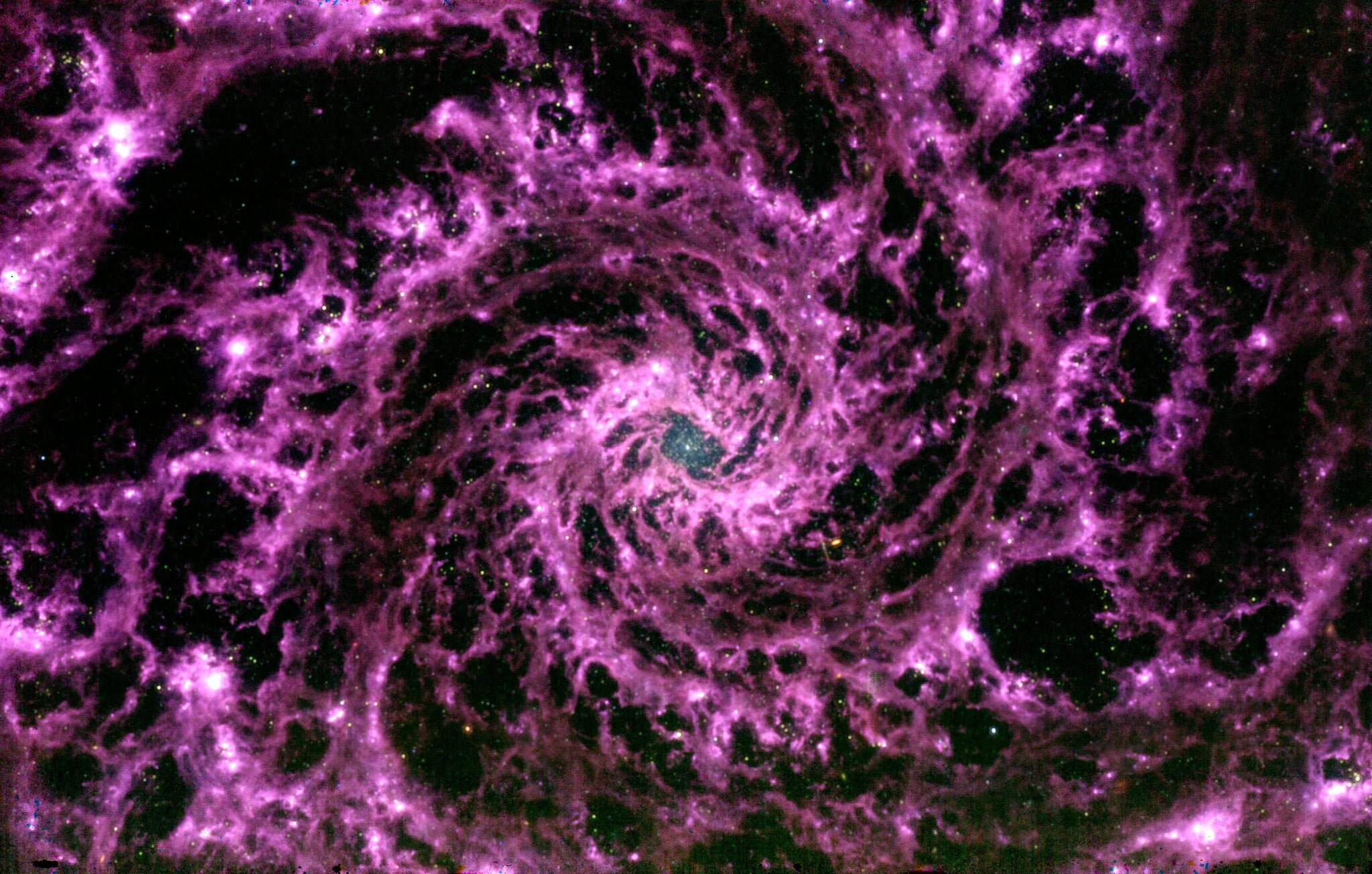

But when he saw a new raw James Webb Space Telescope image of a nearby galaxy on Monday, he couldn’t resist colour processing the image himself and sharing it on Twitter.

“I made it in 10 minutes as I was having coffee,” Dr Brammer told The Independent in an interview, “So it’s not the most carefully created scientific image, but it is scientifically relevant.”

Past images of the galaxy known as NGC 628 taken in visible light by the Hubble Space Telescope, for instance, show the galaxy’s spiral arms strewn with myriad stars, somewhat obscured by filaments of colder dust and gas. But Dr Brammer’s processing of the new Webb image inverts that relationship, hiding the stars and highlighting the dust glowing in the mid-infrared instrument.

The data were actually collected by another team of scientists working on the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS, or Phangs survey, which uses multiple telescopes to study the physics of star formation and galactic evolution. That team has also shared images of other nearby galaxies taken by Webb by posting them on Twitter.

“While that’s not exactly my own research,” Dr Brammer said, “These types of images are how we can really understand the details of what the physics are that are going on [in galaxies].”

But the image Dr Brammer shared highlights more than the exceptional resolution and mid-infrared sensitivity of Webb compared with past instruments such as Hubble and the now retired Spitzer Space Telescope. It’s an example of how Webb is already changing the way professionals and the public interact with scientific images of the deep Cosmos.

A joint project of Nasa, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, Webb was first conceived in 1996, just six years into Hubble’s mission. Webb, as a scientific instrument, benefited from decades of advances in telescope and spacecraft technology between the late 1990s and its launch on 25 December 2021.

But Webb’s ongoing science mission also benefits from terrestrial technology — there was no social media through which to rapidly disseminate different takes on Hubble images in the late 1990s, for instance.

So although Nasa, ESA and CSA all cooperated in a live showcase of the first five full-colour Webb photos on 12 July, the public won’t have to wait for more official releases of Webb images. The telescope is now actively taking images almost constantly now, according to Dr Brammer, and transmitting them to the Barbara Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, or MAST — Webb took the image he shared on 17 July, and he processed and posted it to Twitter the next morning.

“Most of the programs that James Webb is going to do for the next year are these programs called General Observers,” Dr Brammer said. “Essentially anyone in the world can propose an experiment or an observation that they would like Webb to make, and then the community of astronomers meets once a year and reviews all those proposals and makes the decision.”

But the key thing, he notes, is that “The data themselves are available to anybody in the world, not just professionals,” Dr Brammer said. “You can download a Jpeg version of these images directly from the archive.”

Anyone with a copy of Photoshop and enough skills to combine three images of a Webb target into a red, green and blue channel in that image processing software can work up their own full-colour Webb images, he added. And of course, scientists will use the data for research, and sometimes share the resulting processed images with the world through social media and other forums.

“Part of the power, scientifically, of these missions is that these images can be useful for many things beyond what the original team that designed the observations might have thought of,” Dr Brammer said, “because anybody, any astronomer, or anybody else can download them for any purpose that they want and do their own analysis on them.”

And that will translate into a new pace of discovery and revelation when it comes to the results of Webb observations compared with what’s taken place with Hubble and other instruments in the past. A revolutionary, powerful new telescope raining down high definition images of the universe for anyone to process and share and analyze as soon as they care to take a look.

“To some extent, every [Webb telescope] image is going to look like this, and I think that’s part of why I’m so excited,” Dr Brammer said. “But also scientifically, they’re really providing a new way of seeing the universe out to the most distant galaxies.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments