Lunar astronauts could drink and bathe in volcanic ice water

Ancient volcanic eruptions may have left a thick layer of frost on the Moon, now buried beneath the lunar dust

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Future lunar astronauts may slake their thirst, wash up, and fuel their spacecraft with water from ancient Moon volcanoes. As long as they don’t mind a little digging.

That’s the finding of a paper published by University of Colorado, Boulder researchers this month in the The Planetary Science Journal.

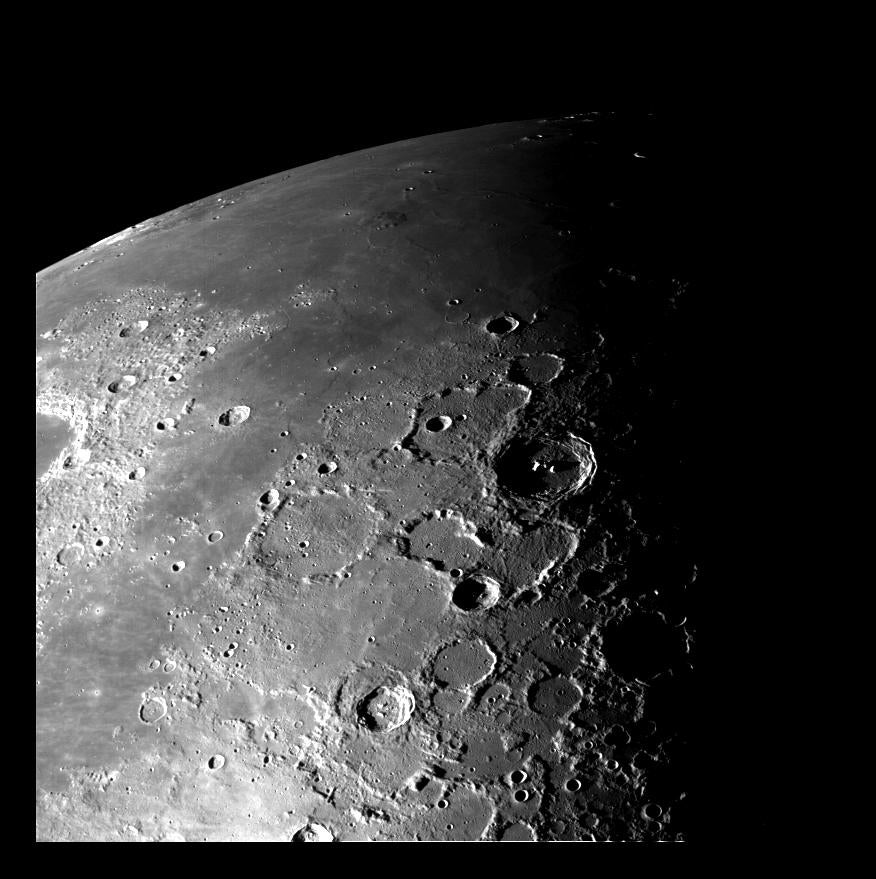

A growing body of evidence suggests the Moon may hold a great deal more water than once thought, hidden in shadowed craters, at the poles. The new paper’s contribution is estimating that much of this water may come from the same massive volcanic eruptions that produced the lava flows that formed the Moon’s Mares, depositing feeding water vapour that froze at locations across all latitudes.

"We envision it as a frost on the moon that built up over time," Andrew Wilcoski, lead author of the paper and a graduate student in astrophysical and planetary sciences and the University of Colorado, Boulder said in a statement.

Over immense stretches of time, that first could have built up to sheets of ice dozens or more feet thick; a boon to lunar explorers in need of local resources, even if they have to move some Moon dirt to get access.

“It’s possible that five or 10 meters below the surface, you have big sheets of ice,” study co-author and assistant professor of astrophysical and planetary sciences Paul Hayne said in a statement. “We really need to drill down and look for it.”

Recent evidence increasingly points to a more hydrated Moon than scientists once expected.

In 2020, Nasa announced research showing water ice could persist in shadows on the sunlit side of the Moon, rather than evaporate in the harsh gaze of the Sun. Where the water ice came from remained uncertain.

The new paper draws on research from 2017 suggesting that lunar eruptions around 3.5 billion years ago released so much gaseous material that the Moon actually had at atmosphere with up to 1.5 times the surface pressure of the current atmosphere on Mars, but this Lunar atmosphere dissipated to space over a 70-million-year period.

Dr Hayne and Mr Wilcoski wonder, however, if water vapour released by the volcanic eruptions might have settled on the lunar surface like frost. Their computer modelling suggested that not only could water ice have formed this way, about 18 quadrillion pounds of water vapour — about 41% of the water vapour released from lunar volcanoes during their active period — could have frozen as ice.

That’s more water than is held by Lake Michigan and that could be great news for Nasa. The space agency hopes to return humans to the Moon in 2025 as part of its Artemis programme, with new missions following roughly once a year beginning in 2027.

Water is heavy, and yet essential. Astronauts need it to drink, to grow food and make rocket fuel. And while spacecraft from Earth can supply Lunar astronauts in a pinch, Nasa is aiming for destinations not so easily reached by resupply missions.

While Artemis missions will study the Moon for its own sake, Nasa also intends to use them as a training ground and launching pad for an eventual mission to mars. Utilising lunar water could be key for astronauts testing the technologies, operations and procedures necessary to live for weeks or months at a time on the lunar and then Martian surface.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments