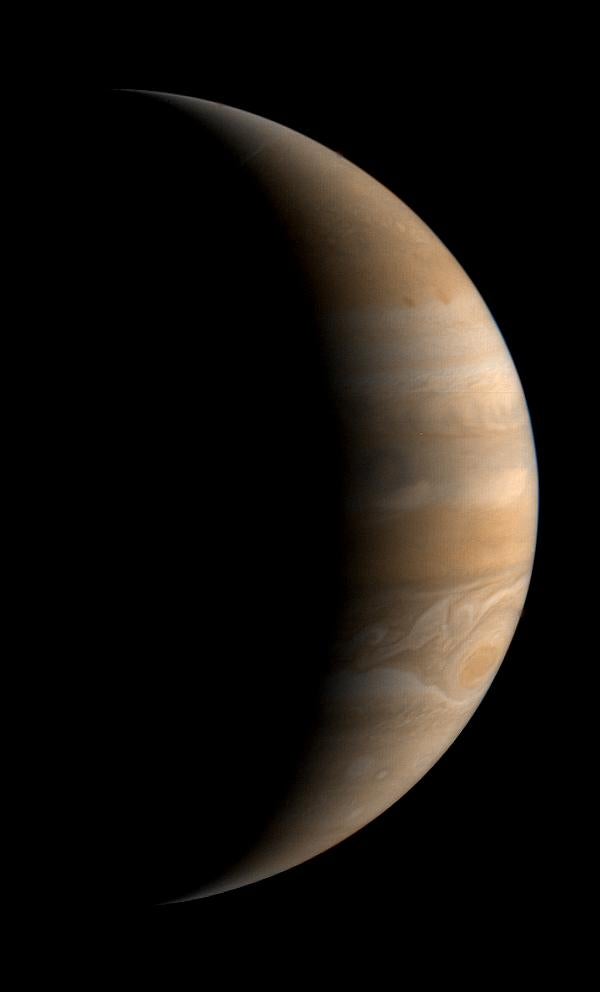

Jupiter may have grown large on a diet of infant planets, study suggests

Nasa’s Juno spacecraft has been orbiting and studying the gas giant since 2016

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In ancient mythology, it's Saturn that devours his children. But in reality, it turns out that Jupiter is the one eating baby planets.

In a new paper published in the journal Icarus, researchers analysing data from Nasa’s Juno mission realised Jupiter’s core is more massive than some past models of the gas giant’s formation would have predicted.

One possible explanation is that Jupiter consumed planetesimals — baby planets — at some point in the past, turning those potential planets into a centre of mass that drew in the rest of the material that formed the big planet.

Jupiter is the largest planet in the Solar System, containing twice the mass of all the other planets combined, having vacuumed up most of the leftover hydrogen gas left over from the formation of the Sun.

That abundant hydrogen makes up the bulk of the giant planet’s vast atmosphere, and at greater depths, is liquified by pressure into a vast ocean of electrically conductive, metallic liquid hydrogen, the source of Jupiter’s humongous magnetic field.

Some theories of Jupiter’s formation hold that the planet condensed out of a vase cloud of gas, with portions of the cloud swirling tighter, and growing in mass until they collapsed in on themselves; somewhat the way stars form, but without becoming massive enough to ignite a thermonuclear reaction and become a small star. Other theories hold that the collisions of small, icy, space rocks may have formed a small seed of rocky mass around which Jupiter as we know it coalesced.

But whether a small rocky core lies at Jupiter’s heart, or it possesses a more “fuzzy” core of heavy elements diluted by hydrogen and helium is not known for certain. As the researchers write in the new paper, “There is no unique solution for Jupiter’s internal structure and more than one density profile can satisfy all the observational constraints.”

Much of what scientists know about Jupiter’s interior comes from gravitational measurements taken by Nasa’s Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting and studying the gas giant since 2016.

It was through analysing the Juno data that the researchers found an anomaly: previous models suggested Jupiter’s core, whatever it consists of, makes up about 10 per cent of the planet’s mass. But in their new models using the Juno data, the researchers found this region makes up 30 per cent or more of the planet’s mass, implying a higher than expected amount of heavier elements than hydrogen and helium.

Several scenarios could explain the new model, but the researchers settle on one they consider most likely: Instead of growing from the agglomeration of small space rocks, Jupiter’s early growth could have been fueled by collisions between much larger planetesimals. This would explain the heavier elements found in Jupiter’s core, but could also have large implications for how we understand planet formation around our Sun and other stars.

Scientists know Jupiter’s gravity affected the formation and orbits of other planets, and that large, early-forming gas giants in other star systems could exert similar influence.

But if gas giants must also gobble up the planetesimals that could, if they survived, one day grow into rocky planets like earth, those gas giants may have even more influence over the formation of other planets — and life as we know it — than once thought.

There are other, if somewhat less possible explanations for Jupiter’s heavy center, the researchers note in the paper, including a giant impact by a large rocky body at some point during Jupiter’s early years.

Knowing for certain will require “future high-resolution observations of planet-forming regions around other stars, from the observed and modeled architectures of extrasolar systems with giant planets, and future Juno data obtained during its extended mission,” they write.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments