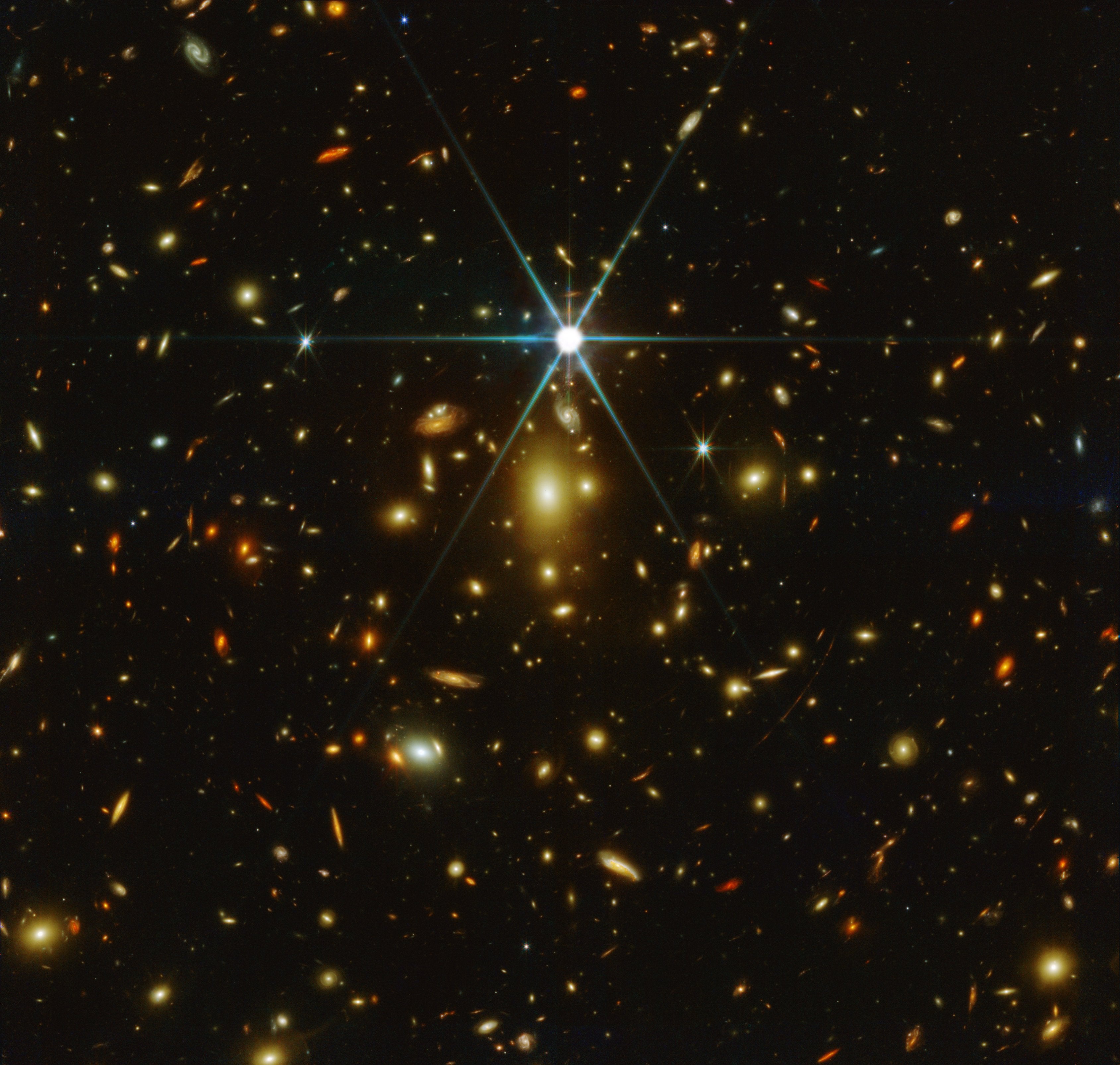

James Webb Space Telescope captures astonishing photo of the most distant star in the known universe

Earendel is 28 billion light-years from our own planet and was discovered just last April

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The James Webb Space Telescope has spotted the most distant star in the universe.

The star, named Earendel after a character in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, is 28 billion light-years from our own planet – twice the distance of the second furthest star, Icarus, which is 14.4 billion light-years away – although when it was first observed the light only took 12.9 billion years to reach Earth.

Earendel is approximately 50 to 100 times more massive than our Sun, with the likelihood being that the star exploded into a supernova just a few million years after its birth.

"We’re excited to share the first JWST image of Earendel, the most distant star known in our universe, lensed and magnified by a massive galaxy cluster," the Cosmic Spring astronomers wrote in the tweet announcing the new image.

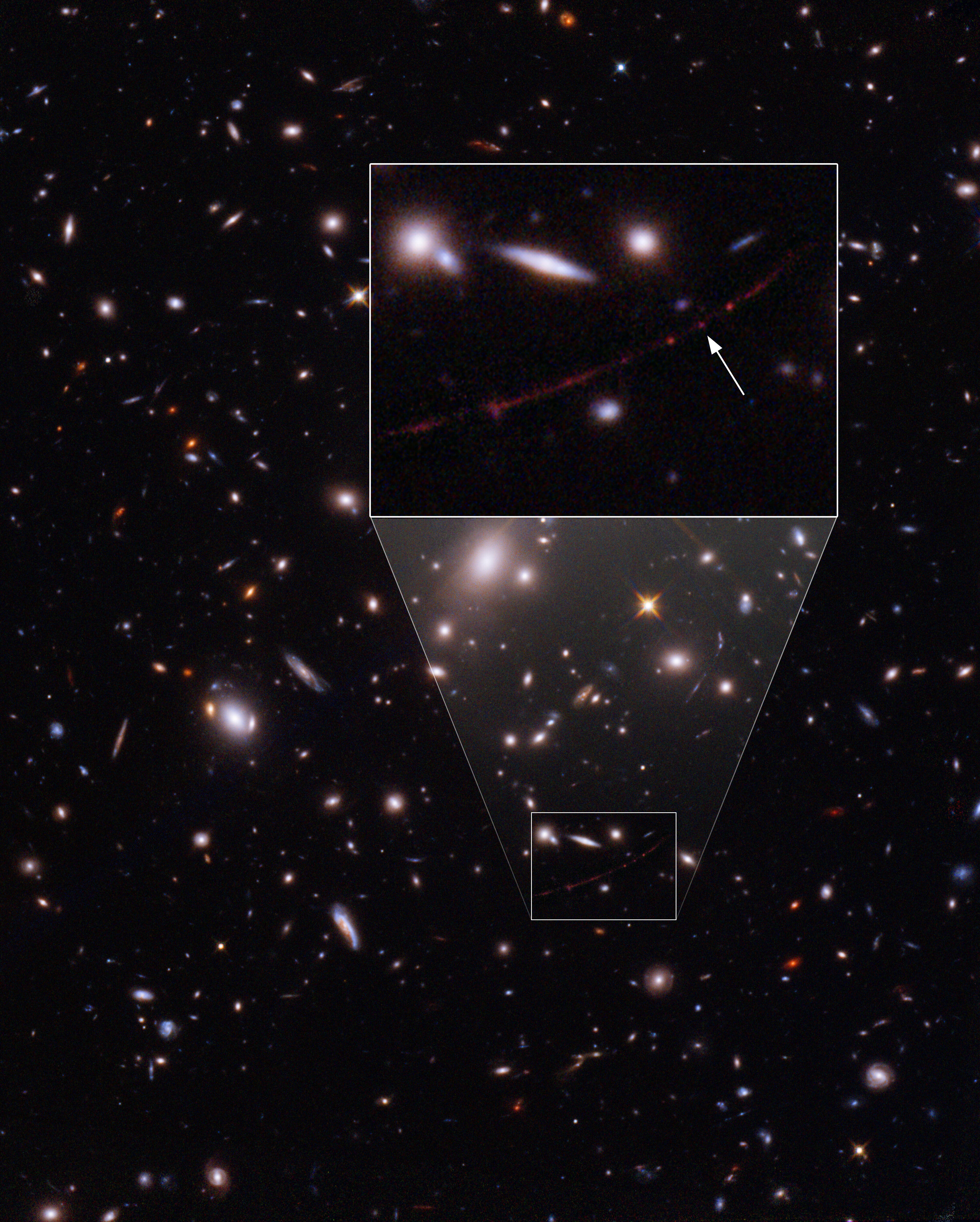

Astronomers can use gravitational lensing to see distant objects more clearly, as the gravity of massive objects distorts spacetime around them, bending light like a magnifying glass. This lets telescopes – even those as expansive as the James Webb Space Telescope – extend their range even further.

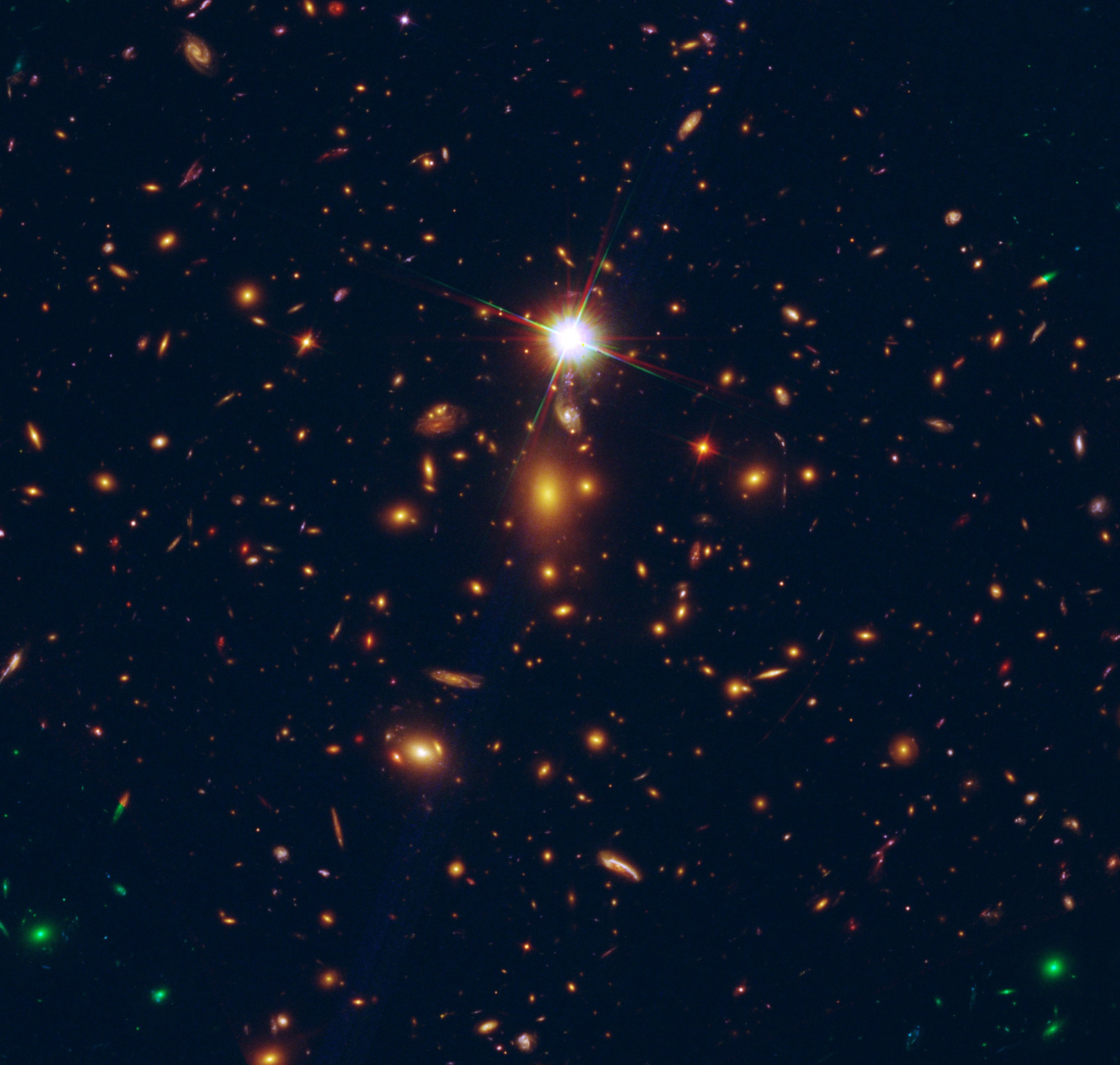

This is how the Hubble Space Telescope discovered Earendel in only April this year, capturing it only 900 million years after the big bang.

“Typically with gravitational lensing with a galaxy, you’ll see multiple images of it,” Brian Welch, a PhD candidate in astronomy at Johns Hopkins University whose research discovered Earendel, said.

“Then, when the alignment is just right, those images merge together into these long, crescent-shaped arcs.”

Earendel is so young that it lacks many of the metallic elements that we find in stars today – it probably contains only hydrogen and helium. “The star is probably going to have fewer of those heavier elements, which means it’s going to be a really interesting way to study what these early generations of stars look like,” he said.

Since its launch, the James Webb Space Telescope has found the oldest galaxy in the known universe, as well as photos of the Carina and Southern Wheel nebulae, a collection of galaxies known as Stephen’s Quartet and a spectrum of light from the exoplanet WASP-96b.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments