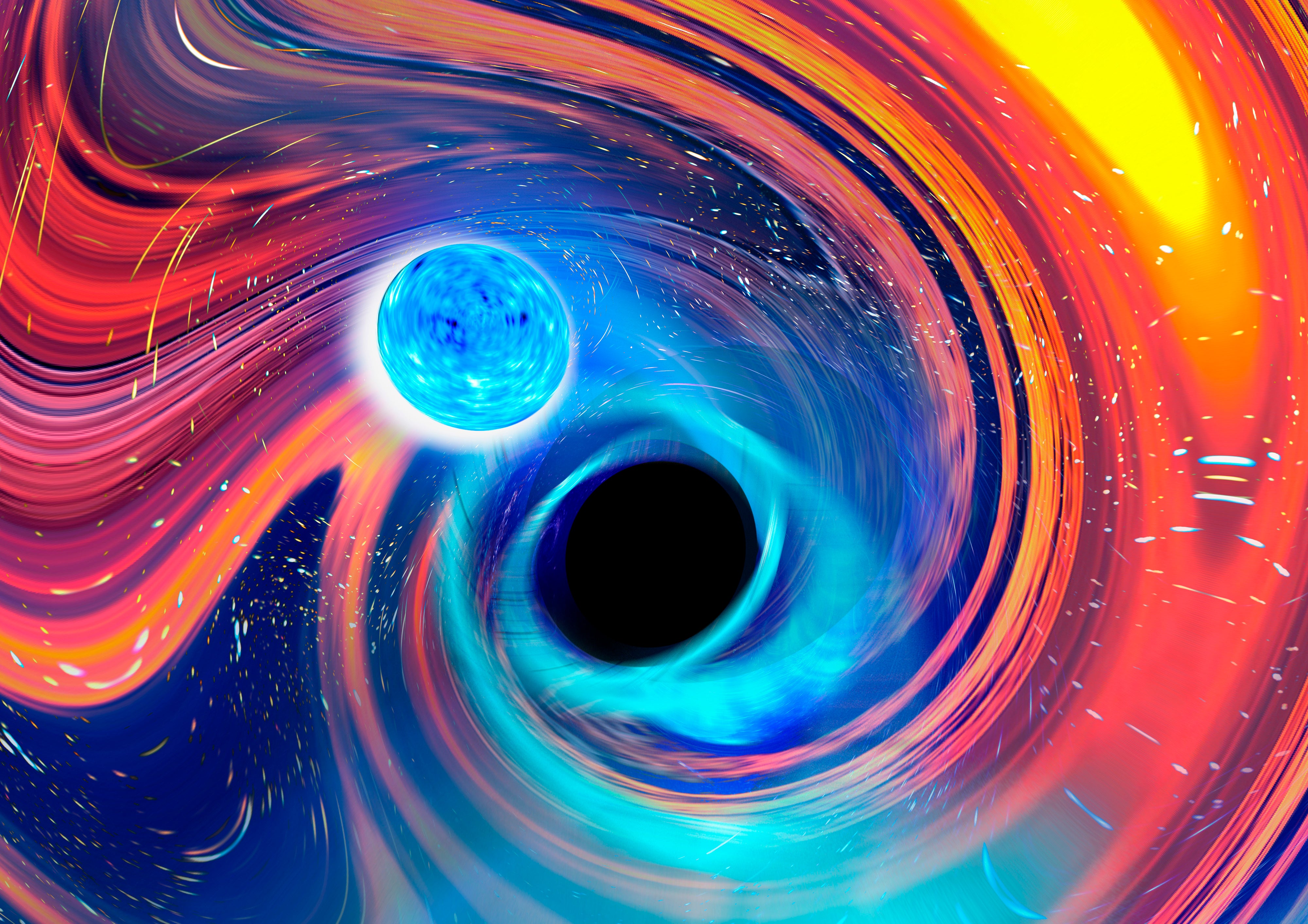

Scientists release huge catalogue of gravitational waves, showing wide variety of black holes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have released a huge catalogue of gravitational waves, showing a wide variety of black holes.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of spacetime that happen during extreme events in the universe, primarily the merging of two black holes.

They were theorised by Einstein but never detected until 2015. Discoveries have accelerated rapidly since, however – with scientists now sometimes seeing multiple gravitational waves on one day.

The latest catalogue includes 35 of those events, bringing the total found to 90.

The catalogue is notable because it includes some rare gravitational waves. While 33 of them come from merging black holes, two are thought to have erupted when black holes and neutron stars merged.

One of them seems to show a massive black hole – about 33 times the mass of our sun – merging with a relatively tiny neutron star, which is just 1.17 times as massive of our sun. That makes it one of the lowest mass neutron stars ever.

Scientists hope they can use the catalogue to understand how stars are born, they die, and what decides whether they become a black hole or a neutron star.

As well as being fascinating in themselves, gravitational waves are useful for so-called “multi-messenger” research. That uses them as a way of exploring distant parts of the universe, alongside traditional signals such as light.

“Only now are we starting to appreciate the wonderful diversity of black holes and neutron stars,” said Christopher Berry, part of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Scientific Collaboration (LSC) said in a statement.

“Our latest results prove that they come in many sizes and combinations. We have solved some long-standing mysteries but uncovered some new puzzles too. Using these observations, we are closer to unlocking the mysteries of how stars — the building blocks of our universe — evolve.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments