Stargazing in December: The moons of Jupiter

Four tiny specks of light close by the giant planet are the biggest of the Jupiter’s 95 moons, Nigel Henbest writes

The king of the planets is at its most glorious this month, shining brilliantly high in the south all night long. On 6 December, Jupiter is at its closest to the Earth – 612 million km away – while the next day it’s directly opposite the Sun in our skies.

Check out Jupiter with a pair of binoculars, and you’ll see it’s not alone in space. Four tiny specks of light close by the giant planet are the biggest of the Jupiter’s 95 moons. If we weren’t dazzled by Jupiter’s own glare, these moons are bright enough to be seen by the naked eye – and some people with unusually acute eyesight can see them without any optical aid. Try this for yourself, by standing where Jupiter itself is hidden by a telephone line and look for any faint ‘stars’ right next to its position. Christmas Eve is a good time for this experiment, as the two brightest moons are then well off to one side of Jupiter itself.

Galileo was the first to describe the moons when he saw them through his early telescope in January 1610. To curry favour with the local aristocracy in Italy, he called them the “Medicean stars.” But the names that won through came from German astronomer Simon Marius, who said Johannes Kepler (author of the laws of planetary orbits) suggested them to him at a fair in Regensburg. In this scheme, the four fainter lights that dance around Jupiter are named after some of the god’s many lovers.

Closest to the giant planet is Io. In myth, she was a priestess, and after Jupiter seduced Io he turned her into a heifer to protect her from his jealous wife. Eventually, Io reverted to human form and gave birth to a son, who was the ancestor of the superhero Perseus (which appears as a constellation in our skies tonight).

In reality, poor Io would be insulted by any comparison with this moon: in close-up, it appears blotched and pustulated, painted in shades of red, orange and yellow. Hundreds of volcanoes are oozing lava and erupted gases up to 400km into space. For its size, Io is the most volcanically active world in the Solar System, driven by heat generated in its interior by the gravitational tug of its neighbouring moons.

The next moon out is named after Io’s great-great-granddaughter, Europa. She caught Jupiter’s eye while she was playing on the beach. To approach the shy maiden, Jupiter transformed into a gentle bull, enticed Europa to climb on his back and then swam off to Crete, where their grandson became the legendary King Minos.

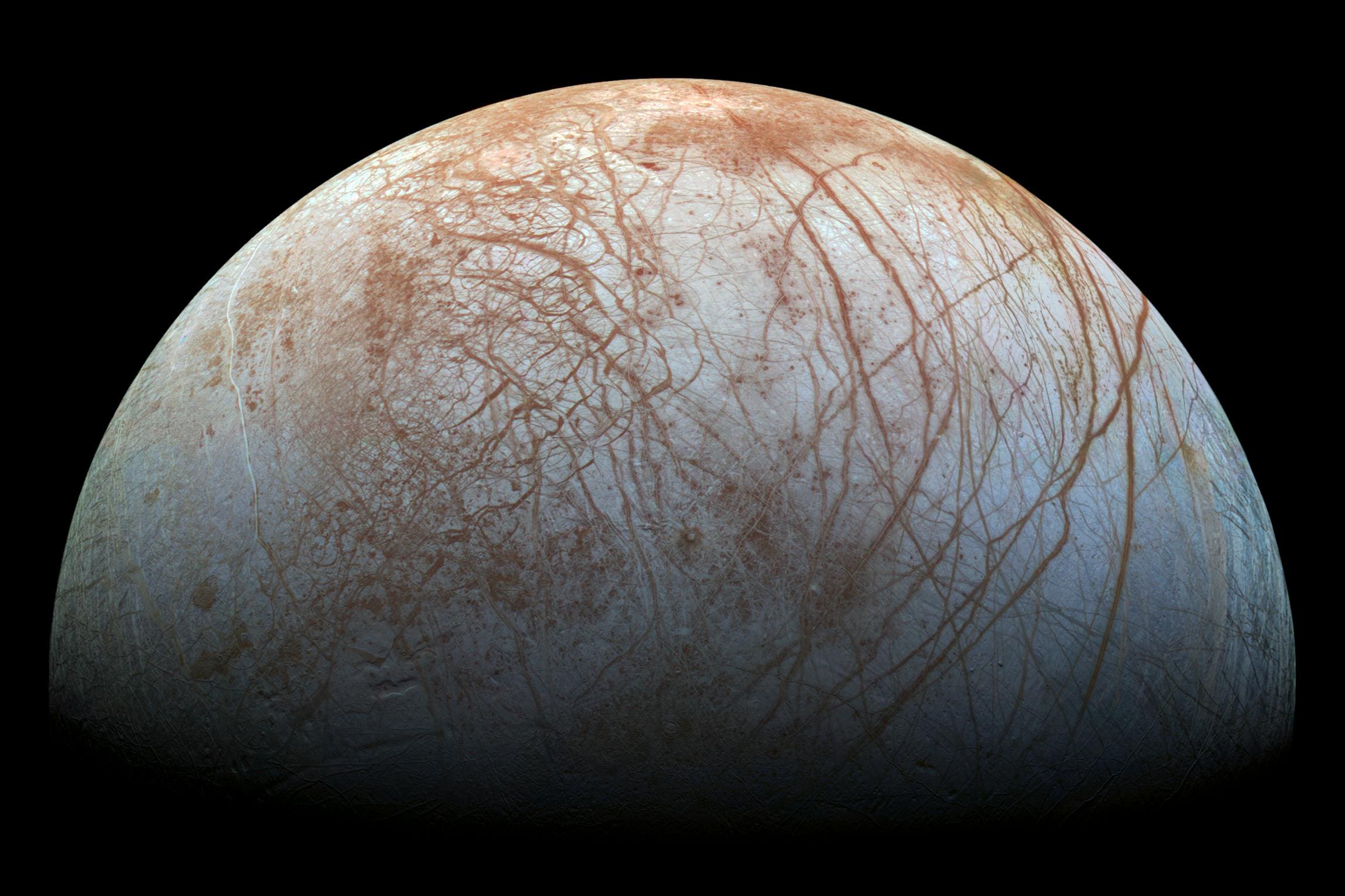

Europa could hardly be a more different world from Io. It appears as smooth and white as the cue ball in billiards. Europa’s surface is a giant sheet of ice covering a hidden ocean, like the sea-ice that blankets the Earth’s Arctic Ocean in winter. Turn up the contrast on images of Europa, and you can make out parallel streaks crisscrossing the surface, where the ice has cracked and then refrozen. Lining these fractures are pale brown deposits that are probably minerals or organic material that has oozed up from the ocean below.

For many scientists, the hidden ocean within Europa is the prime site to find life in the Solar System. It’s kept warm by a more subdued version of the gravitational heating that powers Io’s volcanoes. Liquid water, warmth and organic molecules are the formula for life, and Europa may be home to aqueous creatures swimming freely or clustered around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor.

We’re hoping to discover more when Nasa’s Europa Clipper mission arrives in 2030. Settling into orbit around Jupiter, it will fly low over Europa around 50 times, checking out what materials lie on its surface and – a key objective – to discover the thickness of the icy surface. If there are places thin enough, scientists plan to send a further mission that will drill through the ice to investigate what may be swimming in waters beneath.

Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede, is even bigger than the planet Mercury. In myth, he was the most handsome young man on earth, and Jupiter abducted Ganymede to Mount Olympus to serve as his cup-bearer.

At first sight, Ganymede is not as striking as Io or Europa. It has large dark cratered areas separated by paler regions scoured with long grooves. But there’s evidence Ganymede has a unique interior: above a liquid metal core and a rocky mantle, alternating layers of water and ice form concentric oceans nested together like Russian dolls.

And life may be thriving in one of more of these hidden seas. The European space mission JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) is currently on its way to probe in more detail. It will fly past Europa and Jupiter’s outer moon Callisto, before settling into orbit around Ganymede itself.

Callisto is named after a nymph seduced by Jupiter: when his jealous wife found out, the great god transformed Callisto into a bear – which is also immortalised in the heavens as the constellation of the Great Bear (Ursa Major), with the Little Bear (Ursa Minor) as their son.

As a moon, Callisto is the most boring of the four. Is surface is carpeted by craters, with no sign of any activity since the birth of the Solar System. But for future space exploration, Callisto has one huge advantage over the other three Galilean moons: it lies outside Jupiter’s lethal radiation belt. Nasa has drawn up plans for future human exploration of the outer Solar System, based on a colony on the surface of Callisto. The moon’s ice will provide oxygen for breathing and the hydrogen fuel that explorers will need to speed them outwards to the planets beyond.

What’s Up

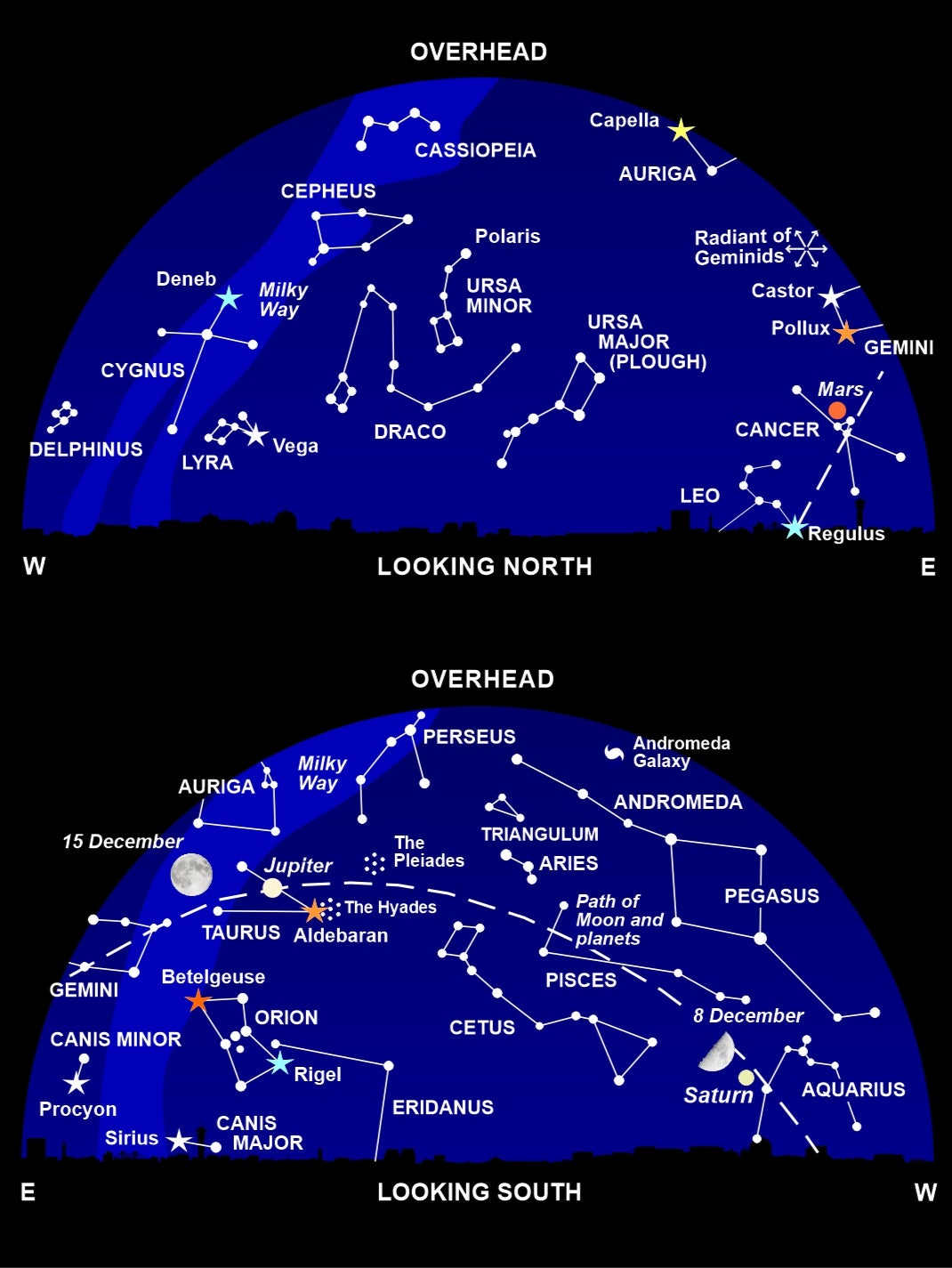

You can’t miss Venus, resplendent in the west after sunset. The Evening Star is gradually moving upwards, and by the end of the month it’s setting as late as 8pm so we can see Venus in its full glory against the dark winter sky.

Well to the upper left of Venus you’ll find Saturn – over 100 times fainter, but still outshining the stars in its vicinity. The Moon lies near Saturn on 7 and 8 December.

The star of the show this month is Jupiter (see main story), second in brightness only to Venus and visible from dusk to dawn in Taurus. The constellation’s major sights lie to the right of the giant planet: the orange star Aldebaran and the glittering star cluster of the Pleiades (the Seven Sisters). The Moon passes above Jupiter on 14 December.

The bright red ‘star’ to the lower left of Jupiter is Mars, During December it doubles in brightness as the Earth approaches the Red Planet. On 17 December the Moon lies between Mars and the twin stars of Gemini – Castor and Pollux – and the following morning the Moon moves in front of Mars between 9.26am and 10.17am.

Shooting stars stream outwards from the vicinity of Castor and Pollux on the night of 14/15 December. The Geminid meteor shower is among the most celestial firework displays of the year, but sadly in 2024 all but the brightest shooting stars will be washed out by strong moonlight.

In the second half of the month, look out around 7am for Mercury, low in the south-eastern twilight glow. The innermost planet is farthest from the Sun on Christmas morning, and the crescent Moon lies just to the right of Mercury on 28 December.

After the winter solstice on 21 December, the nights grow shorter and the days longer, as we head into 2025.

6 December: Jupiter closest to Earth

7 December: Jupiter at opposition; Moon near Saturn

8 December, 3.26pm: First Quarter Moon near Saturn

14 December: Moon near Jupiter; maximum of Geminid meteor shower

15 December, 9.01am: Full Moon

17 December: Moon between Mars and Castor and Pollux

21 December, 9.20am: Winter Solstice

22 December, 10.18pm: Last Quarter Moon

25 December: Mercury at greatest elongation west

28 December: Crescent Moon near Mercury

30 December, 10.26pm: New Moon

Nigel Henbest’s ‘Stargazing 2025’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments