Scientists create vast map of dark matter in the universe

Dark matter makes up most of the universe and decides how it grows – but still remains mostly mysterious

Scientists have created the most detailed map of dark matter in the universe yet – and have used it to make major breakthroughs in our understanding of the cosmos.

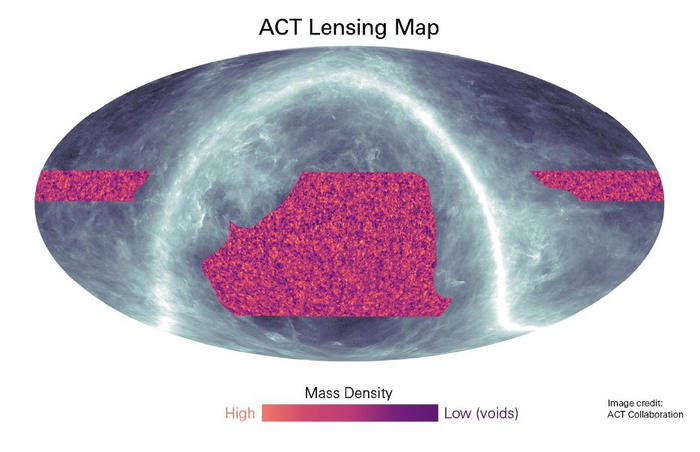

Researchers from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) collaboration used the telescope to build an image of where the dark matter is distributed across the sky, including deep into the cosmos.

It has already been used to confirm a theory from Einstein about how massive structures grow and bend light throughout the history of the universe. And it could help solve an ongoing debate that has led to a crisis in cosmology.

Dark matter makes up almost all of the universe: accounting for about 85 per cent of it and influencing the way it evolves and grows. But detecting and researching it has proven difficult because it does not interact with light or other electromagnetic radiation, and seems only to interact with gravity.

In an attempt to better understand it, more than 160 collaborators used the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile to look at light from the very beginnings of the universe. Scientists were able to look back at a picture of when the universe was only 380,000 years old, which is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation, or CMB.

With that picture of the CMB, scientists can track how it is warped and changed when it is pulled by the gravitational force of the large, heavy structures in the universe. Those heavy structures include dark matter, so that scientists can build a picture of where the heavy “lumps” can be found in the universe.

Scientists found that those lumps were exactly where they would expect to find them, and the same was true of the rate at which the universe is growing. That suggests that Einstein’s theory of gravity and the standard model of cosmology that is based on it is working correctly.

That in itself was a surprise, since recent years have seen frenzied debate on what some have called the “crisis in cosmology”: worries that our model of the universe may be broken, because different measurements that rely on different background light have come up with unexpected results. The new findings instead surprised scientists by matching exactly what they had expected.

“When I first saw them, our measurements were in such good agreement with the underlying theory that it took me a moment to process the results,” said Frank Qu, a Cambridge PhD student who is part of the research team. “It will be interesting to see how this possible discrepancy between different measurements will be resolved.”

ACT was decommissioned in 2022, after 15 years of operation. But new work continues to appear from observations taken during that time, and a new observatory is scheduled to open at the same site next year, mapping the sky nearly 10 times faster than ACT.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks