Astronauts in orbit could be protected by ‘doped’ microbes

Bacteria can cause health issues to astronauts, but can be targetted by specially enhanced microorganisms

Astronauts living and working in orbit could have their spacecraft and suits cleaned by specially developed microbes.

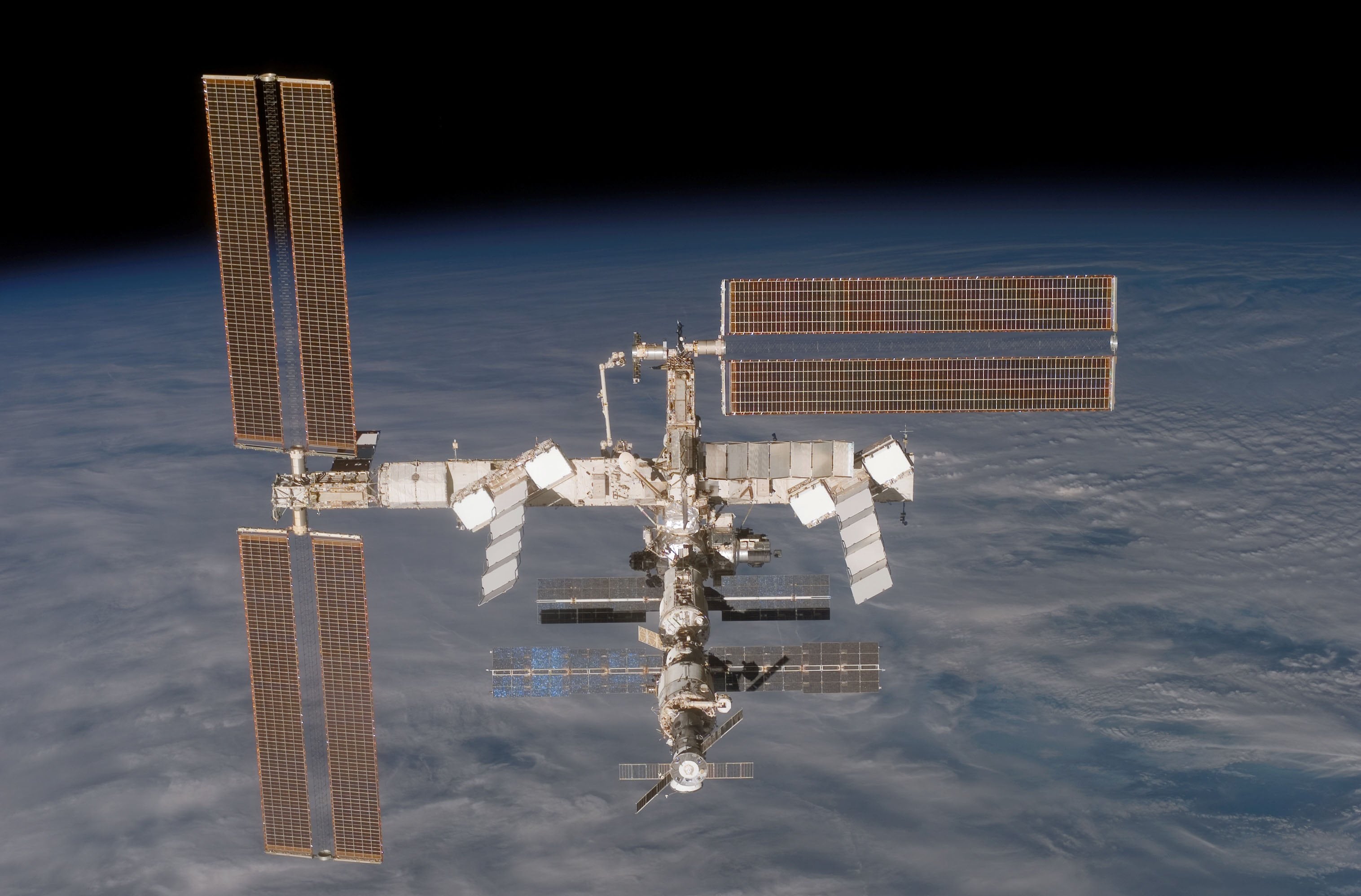

Microorganisms in space present a serious threat to both the health of spacefarers and, in serious enough situations, the structural integrity of the spacecraft. A 2017 study of the surfaces within the orbital outpost of the International Space Station found dozens of different bacteria and fungi species - including harmful pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus that can cause skin and respiratory infections – living outside of Earth.

These bacteria and fungi also produce ‘biofilms’ which can tarnish metal and glass, as well as rubber and plastic.

“With astronauts’ immune systems suppressed by microgravity, the microbial populations of future long-duration space missions will need to be controlled rigorously,” said European Space Agency material engineer Malgorzata Holynska. To combat this, the ESA is studying how antimicrobial materials could be added to internal cabin surfaces.

The team started work on titanium oxide, also known as ‘titania’, which is commonly used for self-cleaning glasses. When the material is exposed to ultraviolet light it breaks down water vapour in the air; this turns it into ‘free oxygen radicals’, incredibly reactive molecules which can interact with every cellular component, and which can attack bacterial membranes.

However, the team is looking into ways to ‘dope’ the compound and making it more sensitive to visible light, as well as making it incredibly thin – between 50 to 100 nanometres, which is millionths of a millimetre – in order to reduce it affecting the mechanical properties of the material it’s on.

“Bacteria gets inactivated by the oxidative stress generated by these radicals,” says Mirko Prato of Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT), which is collaborating with the ESA on the research.

“This is an advantage because all the microorganisms are affected without exception, so there is no chance that we increase bacterial resistance in the same way as some antibacterial materials.”

On Earth, antibacterial coating is often made of silver, but prolonged exposure to the metal on a spacecraft could also have negative affects on scientists’ health. “We don’t want a heavy metal buildup in the onboard water, for instance, with soluble silver linked to skin and eye irritation, even changes in skin colour at very high doses”, Ms Holynska said.

The researchers will also have to examine what happens to the bacteria when the are oxidised again in the cabin atmosphere. “Obviously we don’t want end products that are more toxic than the microbes themselves”, Fabio Di Fonzo of the IIT said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments