Scientists watch afterglow from two huge planets crashing into each other for first time

Amateur enthusiast spotted unusual light from star – and found that it was being covered by the dust from a vast collision

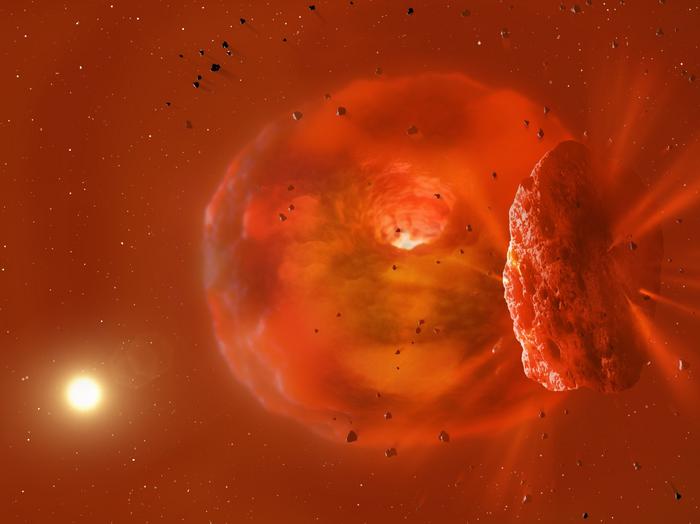

Astronomers have seen the “afterglow” of two huge planets crashing into each other for the first time.

Scientists watched as the heat and dust that were left behind from the crash swirled in front of their star, allowing them to see the aftermath of the explosion.

The incident happened when two ice giant planets collided with each other, around a star like our own Sun. A blaze of light and dust resulted, which could be seen from Earth.

Those effects were first spotted by an amateur astronomer social media, who noticed unusual light coming from the star. It had brightened up in infrared – getting lighter at those wavelengths for three years – and then the optical light began fading.

Scientists then watched the star in an attempt to understand what was happening. They monitored for further changes at the star, named ASASSN-21qj, to see how the star’s brightness changed.

“To be honest, this observation was a complete surprise to me. When we originally shared the visible light curve of this star with other astronomers, we started watching it with a network of other telescopes,” said co- lead author Matthew Kenworthy from Leiden University.

“An astronomer on social media pointed out that the star brightened up in the infrared over a thousand days before the optical fading. I knew then this was an unusual event.”

Their research suggested that the glow was the heat from the collision, which could be picked up by Nasa’s Neowise mission. Then the optical light began to fade when the dust covered the star, over a period of three years.

“Our calculations and computer models indicate the temperature and size of the glowing material, as well as the amount of time the glow has lasted, is consistent with the collision of two ice giant exoplanets,” said co-lead author Simon Lock from the University of Bristol.

The dust is then expected to star smearing out. Astronomers hope to confirm their theories by watching as that happens, since it should be visible both from Earth and with Nasa’s James Webb Space Telescope – and they might see that dust begin its journey into something else.

It will be fascinating to observe further developments. Ultimately, the mass of material around the remnant may condense to form a retinue of moons that will orbit around this new planet,” said Zoe Leinhardt, from the University of Bristol, who was a co-author on the study.

The research is described in a paper, ‘A planetary collision afterglow and transit of the resultant debris cloud’, published in Nature today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks