The £1 homes: What do you get for your money - and what do you get locked into?

Oliver Bennett discovers ways that the less well-off can get a foot on the property ladder and asks if they'll be quids-in

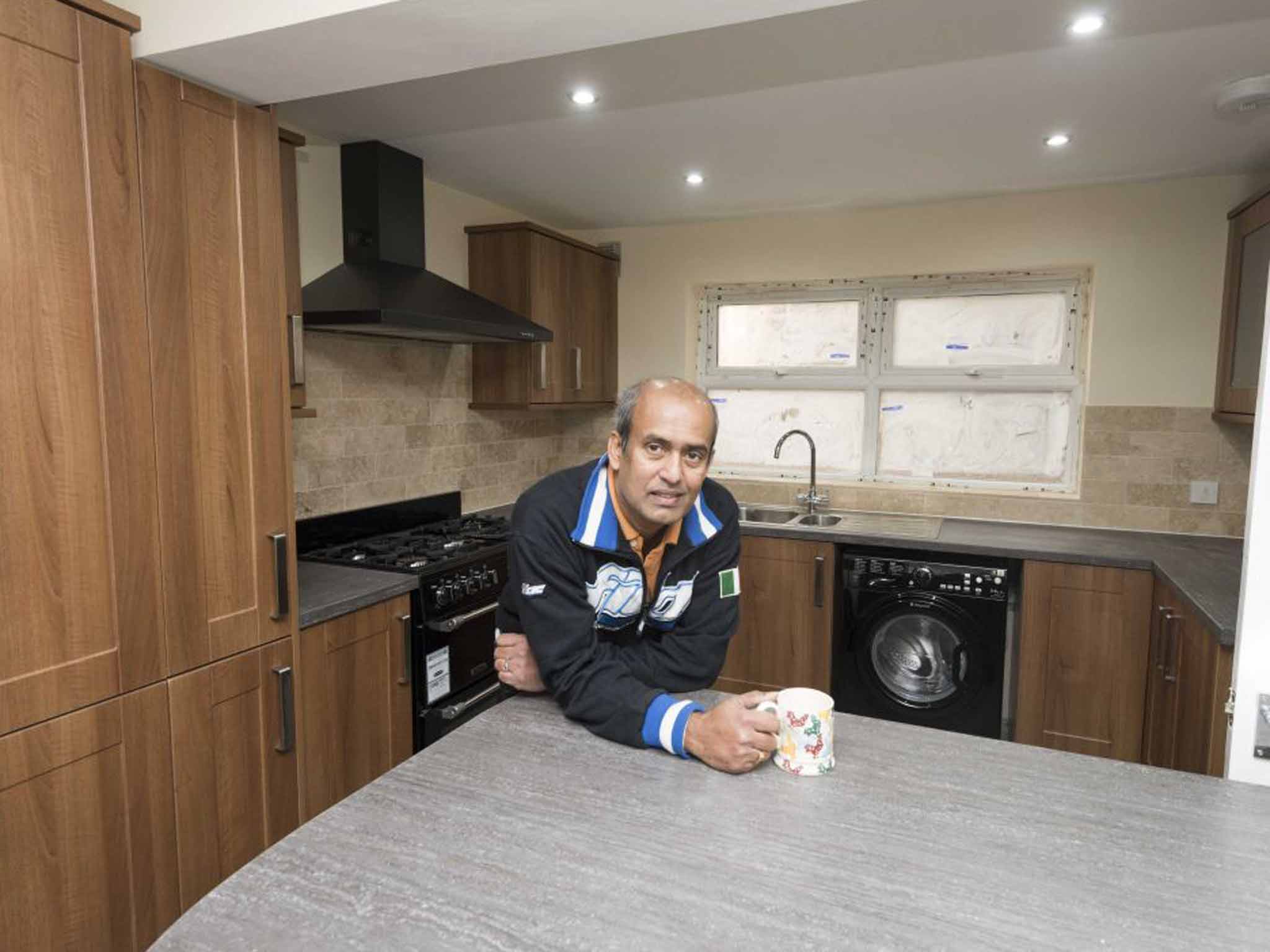

Last summer, just as a £50m apartment was sold on Prince's Gate, London, Gavin Pierpoint moved into a house in Cobridge, Stoke-on-Trent. Although 160 miles away and less grand – Cobridge is a post-industrial area with a canal, old industrial buildings and terraces that had become a bit forlorn of late – Pierpoint's century-old two-up, two-down with a little yard cost the sum of £1. That wouldn't have bought the doorknob in Prince's Gate, where the grand stucco houses overlook Hyde Park.

"I moved out of rented accommodation in Stoke and it's been a great opportunity for me," says civil servant Pierpoint, 28, who found himself successful amid a surfeit of applicants for Stoke's £1 homes. "It's cheaper than buying a house on Stoke's market, you don't need a big deposit and these are good houses that I believe were once built for coal miners."

The UK's new £1 houses have been getting a lot of interest recently. But of course: with an average house price of £180,000 in England and Wales, and £475,000 in London – only an hour and a half away by train to Stoke – they're preposterously cheap. And all eyes are on them as part of a wider plan to bring unused homes back into use across the country. "We see this as a holistic 10-year vision for social uplift and urban renewal," a spokesman for Stoke-on-Trent Council says. Assuming all the plans for renewal of the North and the Midlands take off, it might be the best £1 Pierpoint has ever spent.

True, the £1 is just the start for each owner. Pierpoint's house, like the 32 others in Stoke's scheme, necessitates his taking a £30,000 low-interest loan for renovation, and he has to live there for five years before he can sell (a device to stop "flippers" who might do them up then sell for a profit). Also, applicants for the £1 homes have to be in paid employment, first-time buyers and able to demonstrate that they have both good credit and savings for renovation. But it still means that Pierpoint gets a home below market value, and is part of a process of regeneration.

For all these reasons, the £1 homes have captured the public imagination. One fan is Matthew Rice, an author who is both the co-owner of the Stoke-on-Trent pottery manufacturer Emma Bridgewater and the husband of the woman who gave her name to the company.As he says: "The management of the city council is in touch with best practice and contemporary thinking in urban renewal." Anna Francis, an artist and gallery curator who lives in another £1 house a few streets away from Pierpoint, agrees: "We have to do it up a bit and the area's slightly rough round the edges. But it's great. The area's changing."

A similar project is happening in Liverpool, where 21 £1 houses have been offered in the depressed Anfield area. It has been similarly well-subscribed, with two houses finished and 15 under way so far and, says the Mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson: "Our pilot scheme is transforming run-down properties into beautiful family homes." Indeed, so well has the scheme gone that Liverpool has announced 150 extra £1 properties – which until recently were earmarked for demolition – in Picton. "We're calling it 'Homes for a Pound Plus' because we are doing some of the more difficult work ourselves before handing them over," says a spokesman for Liverpool City Council.

Big works – roofs, floors, walls – can put off some £1-house applicants, as they also did with the Stoke scheme. "But they changed the criteria so you didn't need to do as much," Anna Francis says. "When we moved in, for example, it had already been plastered."

So now you don't have to be a DIY freak or even very handy. Small wonder, then, that the £1 homes are considered a win-win. Not only do they incentivise moving into unused housing stock, they also attract people into depopulated areas. (Liverpool's population was 857,000 in 1931 and, although now rising, is still below 467,000.)

"One-pound houses tend to be in places of significant industrial decline," says Mark Hemingway of the charity Empty Homes, which supports the venture. "There are 600,000 empty homes in England and almost two million people on waiting lists, so we applaud creative local authorities with goodwill and good contractors who see the benefit." Also, while a £1 house's renovation budget may be in the region of £30,000 to £40,000 depending on its state, local authorities are financially incentivised by the Government's New Homes Bonus to bring empty properties back to use.

We all know why. The £1 house sales are happening because the UK is in the grip of a housing imbalance: too many properties in unloved locations, too few in places where people clamour to live. On face value, it's bizarre that while the South-East agonises about whether to build on protected Green Belt land, £1 homes in less pressured areas are luring people such as Gavin Pierpoint and Anna Francis to raise depressed areas from within. But perhaps, by spreading the love, places such as Cobridge will become turnaround districts and in turn help to revitalise the UK's less invested regions, relieving the pressure on prime areas and reversing flight and urban blight. Some will scoff but it is at least possible.

Another kicker for these schemes is that they redress the damage done by Pathfinder, the discredited New Labour scheme to purchase houses in the North compulsorily, knock them down and build new ones. "It destroyed the value of housing and knocked down perfectly good properties," says Clem Cecil of Save Britain's Heritage, which campaigned to preserve Liverpool's historic terraces. "And several of the towns and cities it targeted were beginning to reverse post-war population decline. One-pound houses are a far better solution."

Of course, there are snags and constraints, Hemingway explains. "They shouldn't be done in isolation," he says. "There has to be employment and infrastructure: shops, cafés and a wider regeneration plan." (Why invite people to live in places without transport or industry?) Also, re-population should be planned: buyers don't want to live in the one good tooth in a rotting grimace, where the "broken-window theory" – that neglect and decrepitude attracts crime – can be the experience of daily life. And even now, Anna Francis says, there's a stretch of road nearby she's unhappy about walking down, as well as a lack of facilities, and some slight social strains. "The pub and shop had gone, even a postbox which, despite a campaign, hasn't returned," she says. "There is a bit of fly-tipping and smashed glass, and the urban blight still exists."

But these negative aspects are receding, giving rise to what she describes as "something like an old-fashioned community where children play out and neighbours talk to each other on the street in the evening". Hope also lies in the refurbishment of a local park. Stoke and Liverpool's attitude is: refurbish and they will come. "The more the houses are brought back into use, the more the area comes up and the more they will cost," says Clem Cecil, who worked alongside an estate agent to add market credibility to the campaign to save Liverpool's terraces. "The £1 house has been a complete lifeline. And terraces are high density but low impact – the perfect urban housing model."

Moreover, these places are finding a new fascination as part of an aesthetic of re-use. The art and design group Assemble has been nominated for the 2015 Turner Prize for its work on Liverpool's Granby Four Streets community land trust, while Anna Francis – herself an artist – has made a body of work about the intersections between nature, brownfield sites and old housing including a series of works on "Brownfield Ikebana", a floral arrangement using plants from derelict sites. Regeneration has become art.

Still, there are potential pitfalls. Not all local authorities want to take £1 homes on: in one example, the Accent housing association offered to sell 130 homes to Durham Council for just £1, but it refused. And one can see the problems for local authorities as well as tenants. There's the "opportunity cost" – the fear that refurbishment might push homes over eventual market price – and the calculus that new-builds cost less than refurbished homes and don't need to be retro-fitted.

But public sentiment is with them and, as Hemingway points out, these £1 houses come from a deep and fascinating history of free or cheap land being offered to lure motivated new inhabitants – known historically as "homesteading". In the UK, earlier homesteading schemes have been pioneered in North Benwell, Newcastle (where homes cost 50p in 1999 and are now in six figures), as well as Glasgow, Manchester and Sheffield; even in London in the late 1970s. A thorough paper from Sheffield University has the whole picture, and illustrates that the effects of homesteading have often been highly positive. As Hemingway says: "Some time ago, Hebden Bridge made a decision to sell terraced homes for – if I recall rightly – about £20. Now it's a really vibrant area."

There's an element of frontiership at work, too – particularly in the US, where the US Federal Homestead Act of 1862 allowed new citizens to claim 65 hectares of land; as long as they built a home and farmed for at least five years. Now, with about 15 million empty and foreclosed homes across the country, the homesteading concept has been brought up to date by the federal Dollar Homes project, under the aegis of the Federal Housing Administration, whereby family homes are made available for $1 if they've languished on the market for more than six months.

The scheme mostly applies to post-industrial cities such as Detroit; Gary, Indiana; and Buffalo, New York – though it is hindered by high crime – and inevitably, there have been kerfuffles about homesteading schemes favouring bourgeois gentrifiers. But in the US, there's also the growth of a rural hipster homesteading movement whereby communities in Kansas, Maine, Nebraska and elsewhere have offered free land to attract new, ethically driven residents. "I want to preserve cultural heritages and do things my folks used to do, like canning and making soap," says Steve McNulty of North Carolina's Triangle Area Homesteaders group.

Meanwhile, in gorgeous rural Italy there's another tantalising story: heritage homesteading. "More ancient hamlets here are selling homes at a symbolic price of €1 [71p] in the hope of keeping them alive," says Walter Di Martino of the Italian property portal Gate-Away.com. "It's their answer to depopulation."

They include Salemi and Gangi in Sicily, Carrega Ligure in Piedmont and Lecce nei Marsi in Abruzzo – and they're lovely. But before you head to the nearest Ryanair terminal, there are conditions: for example, in Gangi buyers have to pay a €5,000 guarantee to the local authority and, although money will be redeemed once restored, they have five years to do them up (which might cost upwards of £30,000 and include tricky stuff such as sewage). There are also legal costs attached to buying properties: often about £5,000.

Closer to home is the Normandy village of Champ-du-Boult, where four plots of 900 sq m to 1,000 sq m are currently being offered for €1 per square metre: again, an effort to augment the population of 388 with self-building residents.

So, in more ways than one, homesteading schemes and £1 houses are a way of finding value. And back in Liverpool, they're bullish. "We're now looking at a Shops for a Pound scheme on Smithdown Road – the same concept but with shops rather than houses," says the council's spokesman. So, as London topples under the sheer weight of financial gravity, perhaps the next property prize will go to the new homesteading generation. Building the new Jerusalem with elbow grease and a quid.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments