Anna Pavord: 'Trees lift our spirits, shade us, boost the environment - but which ones are right for your garden?'

With the tree-planting season approaching, our gardening correspondent reveals what she would choose for an urban garden

The London i-Tree eco project, a survey of the city's trees and their value to the ecosystem (the full findings of which are to be published soon) has thrown up some interesting early results. It found that there are as many trees in London as there are people: 1.5 million in inner London, 6.8 million in outer London. This makes London one of the most arboreal cities in the world, but the surprise is that the majority of trees aren't in public spaces, but private ones.

In outer London, the survey revealed that 81 per cent of trees are privately owned. Public or private however, we all benefit. Trees store carbon, both above and below ground. Through photosynthesis, they take in carbon dioxide and give out oxygen. They reduce air pollution. They suck up rainwater and help to regulate air temperature.

The i-Tree survey, based on an American model that has been used throughout the world, focused on these environmental benefits and the economic value they represent. In Torbay, Devon, where the same project model was used a few years ago, the tree officer estimated that the carbon storage of the Torbay trees (mostly ash there) was worth £1.5m, the pollution removal worth £1.3m. But I'm slightly wary of this approach. It misses out other equally important benefits that trees give us: how good they make us feel, how they lift our spirits, above all, their beauty. What price beauty?

But it's evidently easier to win arguments – and budgets – if you've got figures to throw at the purse keepers. And without the London survey would we have known that the London plane, though only the fifth most common tree in inner London, stores the largest amount of carbon and offers the greatest canopy cover? Canopy cover is the key to the amount of air pollution a tree can remove. It also provides shade, welcome to anyone who has ever trudged through London streets in a heatwave.

So which are the most common trees in the capital? In inner London, birch, lime and apple top the list. In outer London it's sycamore, oak and hawthorn. In all, the surveyors found 112 different kinds of tree, with private gardens making an important contribution to the diversity. So with the tree-planting season approaching, which trees might you think of putting in an urban garden?

You have first to be absolutely clear about what you want the tree to do. Does it have to screen something you'd prefer to not see? In which case, you need to think about height. Do you want to sit under it and have a drink or supper on a summer evening? In which case, you don't want a tree that droops its branches too close to the ground.

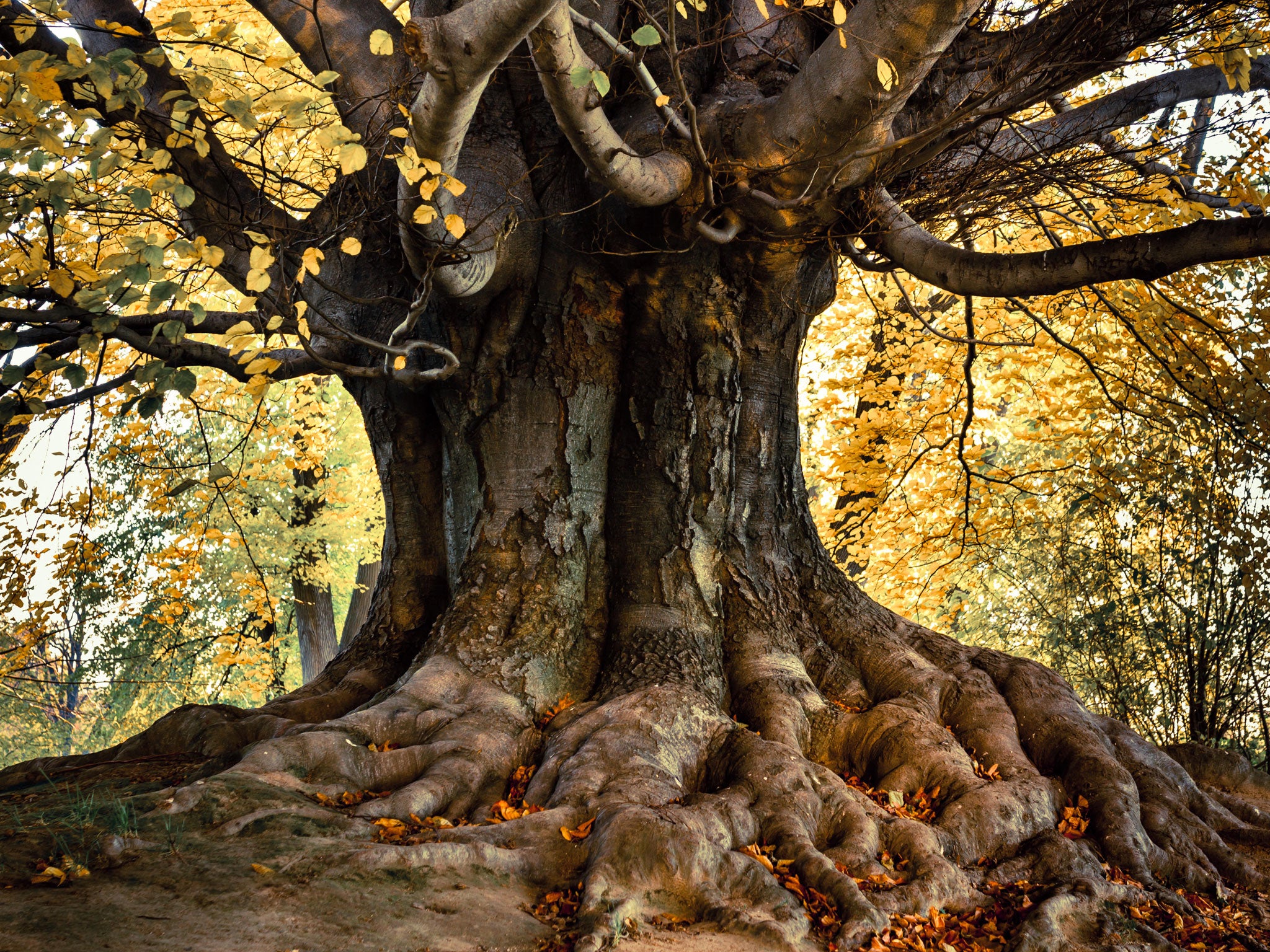

Most of all, you need to check a tree's eventual size. We need big trees, as the survey shows, but it's cruel to plant a lime or a London plane or an oak in a space that it will outgrow within 20 years.

The same goes for the monkey puzzle (Araucaria araucana), which I frequently see planted out as a baby in London front gardens. Especially in Clapham. It might seem deliciously edgy, spare, strange, just the thing to contrast with the slate chip mulch. But on the volcanic slopes of the Chilean Andes, where this creature is at home, it can reach up to 25m/80ft and spread its branches across 10m/30ft of ground. That is its destiny, and it's not a tree you can cut down to size.

In a small space, I'd be thinking of a tree that had more than one season of interest. My first choice would be a pear. I like the shape a pear tree makes, rather narrow in proportion to its height. In a small garden, that's a useful attribute. The first tree I ever planted in our present garden was a tall, elegant pear called "Chanticleer," which blossoms very early and turns a wonderful butter yellow before the leaves fall.

But it's not a pear for eating. The fruits are small and hard. For a harvest as well as blossom, I'd choose something like "Clapp's Favourite," which is of naturally upright growth but no taller than 4m/12ft. Or "Louise Bonne of Jersey" which ripens about now, and again is also fairly upright in growth.

Crab apples make excellent trees for town gardens too, provided they're not the kind with purple foliage. These look passable when the leaves first emerge in spring, but as summer moves on, the colour becomes ever more heavy and dismal. Malus hupehensis is much easier to live with, though eventually it will make a tree as wide as it is high. The flowers are scented, opening white from pink buds, while the fruits are about the size of cherries, and a good clear red.

Whatever variety of tree you choose to plant though, choose it because you love it, not just because it's going to offset your carbon footprint.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments