Anna Pavord on Great Dixter: 'There's a dynamism you don't find anywhere else'

Nearly 10 years on from the death of the great Christopher Lloyd, the garden he created at Great Dixter in Sussex has retained all its joy, exuberance and subversiveness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

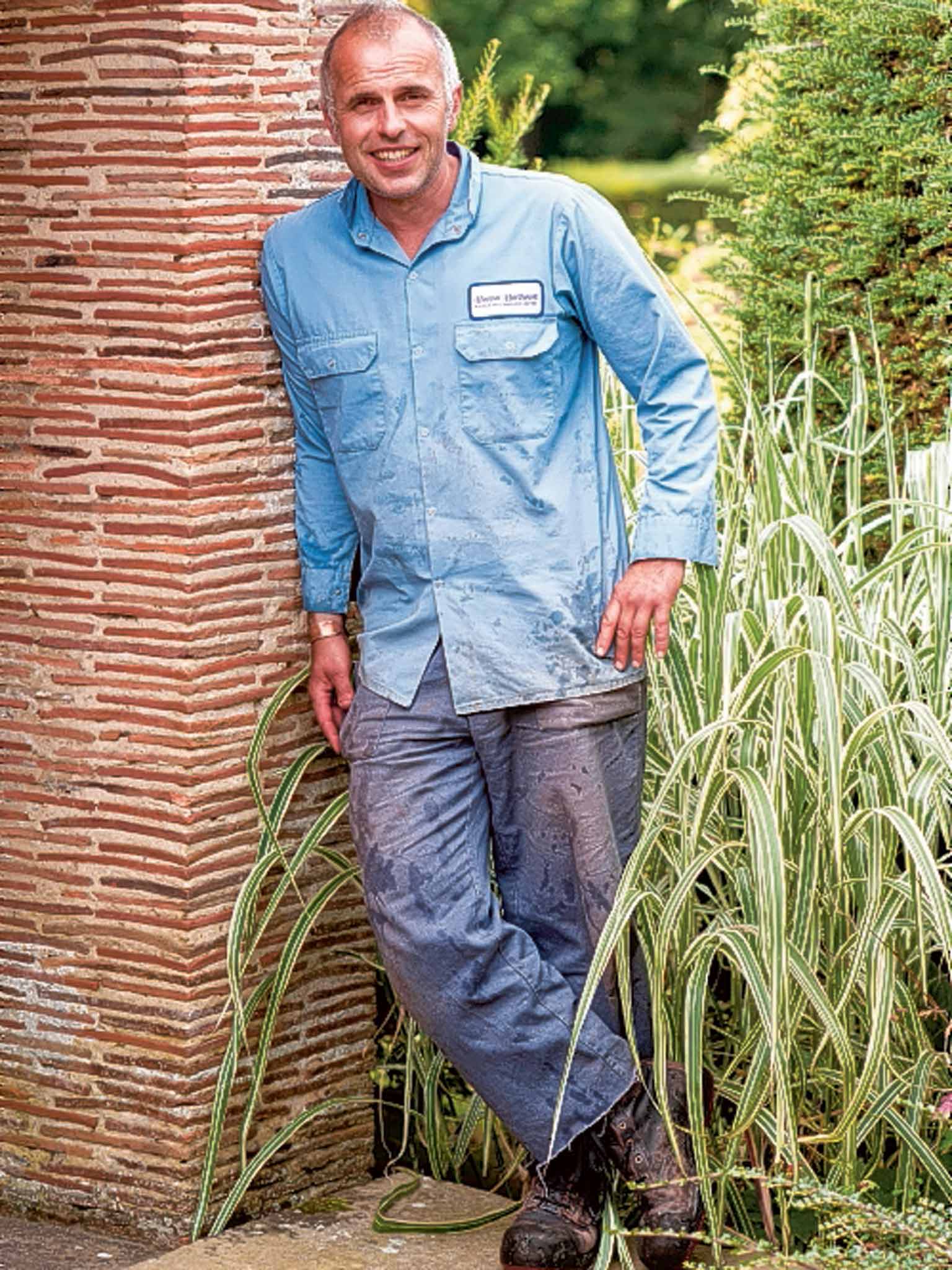

Your support makes all the difference.Of all the gardens in Britain, Great Dixter in Sussex is the one I know best. Way back, I commissioned its owner, Christopher Lloyd, to write a gardening column and it was the beginning of a friendship that lasted for decades until his death. He died almost 10 years ago, but thanks to his brilliant head gardener, Fergus Garrett, the place still has the joy, exuberance and wild energy that I always associated with Dixter.

Fergus – half Turkish, half Irish, wholly original – was the one who first suggested that the grass roundels of Edwin Lutyens' formal steps might be bedded out with cactus. Fergus encouraged Christopher in his plan to do away with the Edwardian rose garden and fill it instead with the kind of dramatic, exotic foliage you are more used to seeing in the Caribbean.

Christopher was born at Dixter House in 1921, and lived there for most of his life. The bones of the garden are still essentially those laid down by Lutyens, working with Christopher's father: broad yew hedges, wide terraces, topiary, flagstone paths, an archetypal Edwardian arts-and-crafts design.

The wonderful thing though is the way that the fine, strong layout, done more than a hundred years ago, not only accommodates but enhances a style of planting that has absolutely nothing to do with formality or restraint. You see this most clearly perhaps in the High Garden, a series of enclosures that originally formed part of the working, rather than the display garden. For many years, it was where stock plants were set out in rows to supply the nursery at Dixter. But Fergus, while still keeping the stock plants the nursery needed, rearranged them in high-spirited, dynamic swathes of cleverly contrasted foliage and form.

The wonky old espalier apples and pears lined out along the paths stayed true to their Edwardian pedigrees, while behind them, wild fennels were reared into flower on 12-foot stems and strange umbellifers spread out their flat heads over the clumps of daisies and perennial sunflowers that dominate the late summer season.

I was there in late June, when an opium poppy (it's called "Lauren's Grape") was laying trails of deep purple through one of the beds in the High Garden. At first I supposed they had self-seeded. "No," said Fergus, who was with me. The poppies had been raised from autumn-sown seed, pricked out individually into trays of plugs, then planted out as baby seedlings from the plugs, before the roots began to resent their containment.

And that explains why the effect was so electrically brilliant. The poppies weren't random at all. They had been threaded through the other plants in a very deliberate, connected way. And yet the effect would necessarily be evanescent. The opium poppies, fabulous when in flower, only last a couple of weeks. "But the foliage is good," Fergus said. Which it is. And earlier in the season, it would have provided a useful wax-grey background for the tulips, bedded out up here for a spring display.

There was a tiny, beaten-earth path leading through one of these so-called stock beds, almost obscured by the papery drooping lockets of the annual quaking grass, Briza maxima, grown from seed and planted out earlier in spring. It was one of the best paths I took that day at Dixter. It immerses you in the dynamic extravaganza of the Dixter style. You are like a swimmer at sea, just about maintaining the equilibrium. But only just.

The approach to Dixter, through the small wonky wooden gate (a Lutyens design) immediately sets the style. The grass either side of the central path is allowed to grow long under old pear trees. "Problem with the mower?" a visitor once asked Christopher. "The problem lies with the visitor," he replied sharply.

He (and before him, his mother) were early enthusiasts for the meadow style. She began her experiments in the remains of the moat at the back of the house. Christopher introduced camassias into the grass beside the entrance path, along with brilliant magenta gladioli. But in style, the meadow is more wild than tamed, just tweaked here and there with flashes of introduced colour like the gladioli. When I was there, the wild orchids were at their absolute best, scattered liberally through the waving grass stems,

The stone-flagged entrance leads straight down to a generous timber porch, with Christopher's bedroom above. Since Fergus's arrival at Dixter, in 1993, the displays of pots either side of the door have become more and more outrageous. He uses plants like an artist might use paint: a swirl of deep red from some well-grown snapdragons, a hint of cream and purple from some late irises, a furcraea erupting into flower with a spike of candy-floss pinkness.

Each of the plants is in a separate pot and when one thing goes over, something else will be brought in to take its place – Geranium maderense perhaps or the shiny black heads of a succulent aeonium. Subversively, Fergus introduces dwarf conifers as well. It's a joke against Ghastly Good Taste.

Christopher had the same delight in overturning received notions of how things should be. I remember when the close-mown grass of the topiary lawn, at the far side of the moat, was first allowed to grow long. The topiary – an Edwardian collection of peacocks and yew castles – was still clipped, but the formal setting began to dissolve in a miasma of tall, waving grass heads. Now the topiary shapes look as though they are floating, with wild orchids thicker here than anywhere else.

There's a dynamism about Dixter you don't find anywhere else. The high-spirited young gang that garden there – they come from all over the world to learn with Fergus – give it a special animated vigour. They work very hard because the Dixter style demands it. But the rewards! Oh the rewards!

The garden at Great Dixter, Northiam, Rye, East Sussex TN31 6PH is open until 25 Oct, Tuesday-Sunday (11-5), admission £8.80. For more information call 01797 252878 or go to the website at greatdixter.co.uk

WEEKEND WORK

WHAT TO DO

* Satisfying though the sight of freshly turned earth is, moisture in the soil will be better conserved if you mulch round vegetables after you have weeded them. Outdoor tomatoes respond well to being packed round with grass cuttings, as do courgettes, cucumbers and sweetcorn.

* Cut down flowered stems of aquilegia and sweet rocket that you do not want to self seed. Twist bits of string round the stems of plants such as foxgloves that you want to spread, to remind you which are the good ones. When the seedheads have ripened, pull up the whole plant and wave it over the areas that you want colonised.

* It's time for cabbage and broccoli plants. Water well when you plant them out, firming the earth down around the roots. As they grow, mound compost round the stems to provide rich food. This also provides extra stability.

NEWS

* Willerby Landscapes has won the tender for sourcing the planting for the proposed Garden Bridge over the Thames in London. The design by Dan Pearson calls for 270 trees and 64,000 bulbs. But the London Wildlife Trust and the RSPB oppose the project and there is £50 million to find before the £175m cost is met. See more at gardenbridge.london

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments