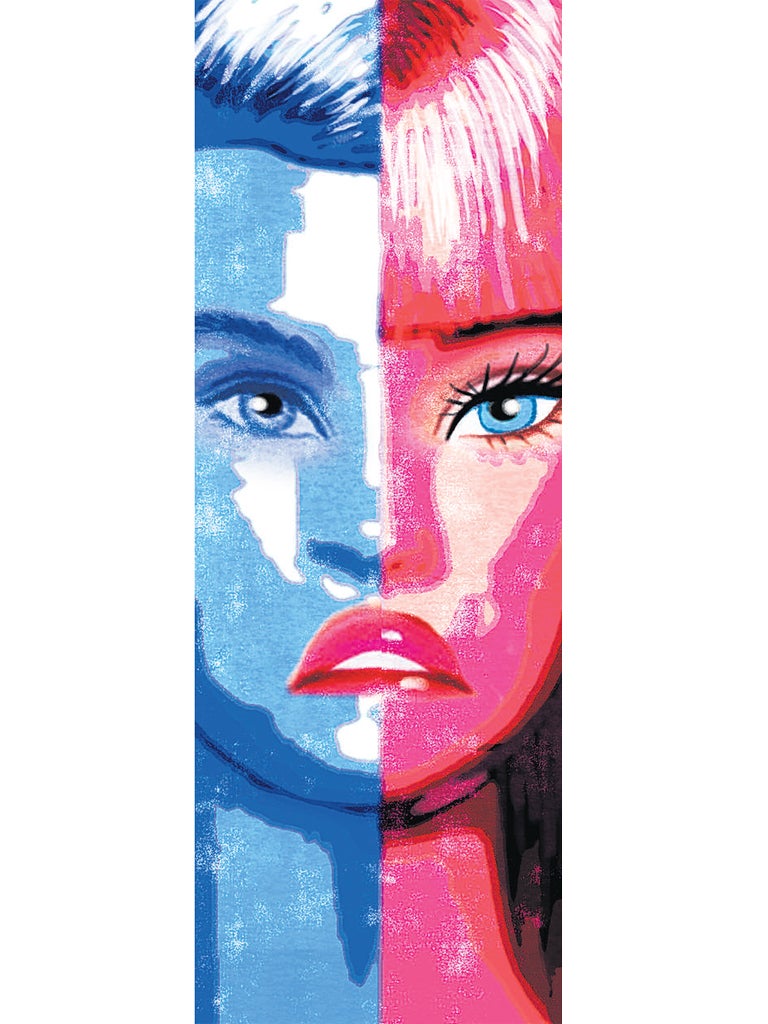

Mary Ann Sieghart: It's up to parents to resist the tyranny of the pink princesses

I begged my parents for a carpentry set. Would I have dared brave the boys' floor at Hamleys?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On our kitchen wall are photos of our two daughters as a toddler and a baby. The older one is in navy blue and dark green, the younger in a red-and-blue checked shirt and cute little red trousers. Only the other day, our 18-year-old asked, "Why did you dress us as boys when we were little, Mum?"

The answer is that I didn't. I just dressed them as children. When our daughters were little, Babygros came in white, pale blue, yellow, lilac, red, navy and, yes, pale pink. But there was no pressure to put the girls in pink. In fact, most of their baby clothes were hand-me-downs from their male cousins and no-one even noticed.

It is only in the past decade or so that saccharine pink girliness has spread through Britain like the Ebola virus. These days, most babywear websites have a "girl" and a "boy" section in which not just the clothes but the bibs, booties and blankets are colour-coded. (Kudos to Mothercare, which allows babies to be "unisex" up to the age of one.) And the virus has spread to toys, too. If you've done any Christmas shopping for children this year, you'll have seen the floor-to-ceiling walls of sickening pink fluffiness in the girls' section and all the fun action and adventure toys in the boys'.

When I was little, I begged my parents for a carpentry set. (The saw had to be confiscated after they spotted the notches in the playroom table.) Would I have dared brave the boys' floor at Hamleys for it? Would my brother, who turned into a fine cook, have ventured into the ocean of pink for a pots and pans set? I doubt it. Hamleys finally agreed last week to relabel and reorganise its toy sections. Hurrah for that. But it's still worth asking whether this toy and clothes apartheid is damaging the way our children grow up.

It's not as if a preference for pink is innate in girls. A recent study by psychologists at New York University offered small children a choice of two objects, of which one was pink. Before the age of two-and-a-half, both boys and girls chose pink objects around 50 per cent of the time, just as you would expect if they were choosing randomly. Only between two-and-a-half and three years did girls start showing a marked preference for pink and boys start avoiding it. By four, girls chose pink nearly 80 per cent of the time and boys just over 20 per cent. They had looked at the world around them and absorbed its message.

And the message is a horribly polarised one. A survey of TV ads for children's toys found that the most-used words for boys were "battle", "power", "heroes", "ultimate", "rapid" and "action". For girls, they were "love", "magic", "style", "babies", "fun", "hair" and "nails".

Toy manufacturers justify this by citing innate differences in boys' and girls' tastes. It is certainly true that boys show more interest in rough-and-tumble from an early age (though this might be because parents are more physical with them). And it's also true that at two, girls marginally prefer to look at a doll's face over a car, with boys the other way round. But the difference is far too marginal – 52.7 compared with 47.9 per cent – to justify the utter segregation of toys between the sexes.

Manufacturers know that girls will, generally, gravitate towards the wall of pink because of peer pressure. It can't be hardwired because the pink-for-girls, blue-for-boys rule came in only after the Second World War. As recently as 1918, the American trade paper Earnshaw's Infants' Department wrote: "The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl."

Other sources at the time said blue was flattering for blondes, pink for brunettes; or blue was for blue-eyed babies, pink for brown-eyed ones.

But if little girls see other little girls in TV ads or at nursery obsessing over pink princesses and ponies, that's what they'll want for themselves unless they are very strong-minded. And boys will assume that they are only allowed to play with things that go "vroom, vroom" or "bang, bang". Boys are much more inclined to play with dolls on their own than when they are with other boys.

You can see why all this is in the manufacturers' and retailers' interests. As the youngest of four boys and girls, I lived happily in the hand-me-downs of my older brothers and sisters. These days, though, parents who already have a child of one gender feel they have to buy completely different clothes and toys when they have one of another. So the shops sell twice as much stuff. Even gender-neutral things like bikes and board games are now segregated. Monopoly – for God's sake – has a "Powderpuff" and a "Pink Boutique" version: "Comes in a pink jewellery box!". "Playing pieces include handbag, mobile phone!". Makes you want to weep.

This isn't good for either sex. Girls are being taught to aspire to be a princess – whose main job is to wait for her prince to come, and to doll herself up in the meantime. It is a passive role in which the dominant desire is to be desired. They aren't encouraged to be an active or brave agent, like a fireman or soldier or doctor or train driver. Boys lose out too, though. If they fear they can't go near a craft set or a doll, then they won't have a chance to indulge the creative or loving side of their nature. Why should love be reserved only for females? Or cooking, for that matter?

This gender-stereotyping of toys isn't trivial; it feeds through into later life. Look how many more teenage girls say they want to be a hairdresser than an engineer. Expectations even affect performance. A recent Stanford University study showed that female students perform worse in maths tests if they are told before the test that men are better than women at maths. If they are told there is no difference between the sexes, they actually outperform the men.

So if we want our girls to fulfil their potential, and our boys to develop compassion and creativity, we must not allow the commercial world to narrow their ambitions. Just as society is becoming more equal, the business of childhood is pushing boys and girls further apart. It is a trend that parents desperately need to resist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments