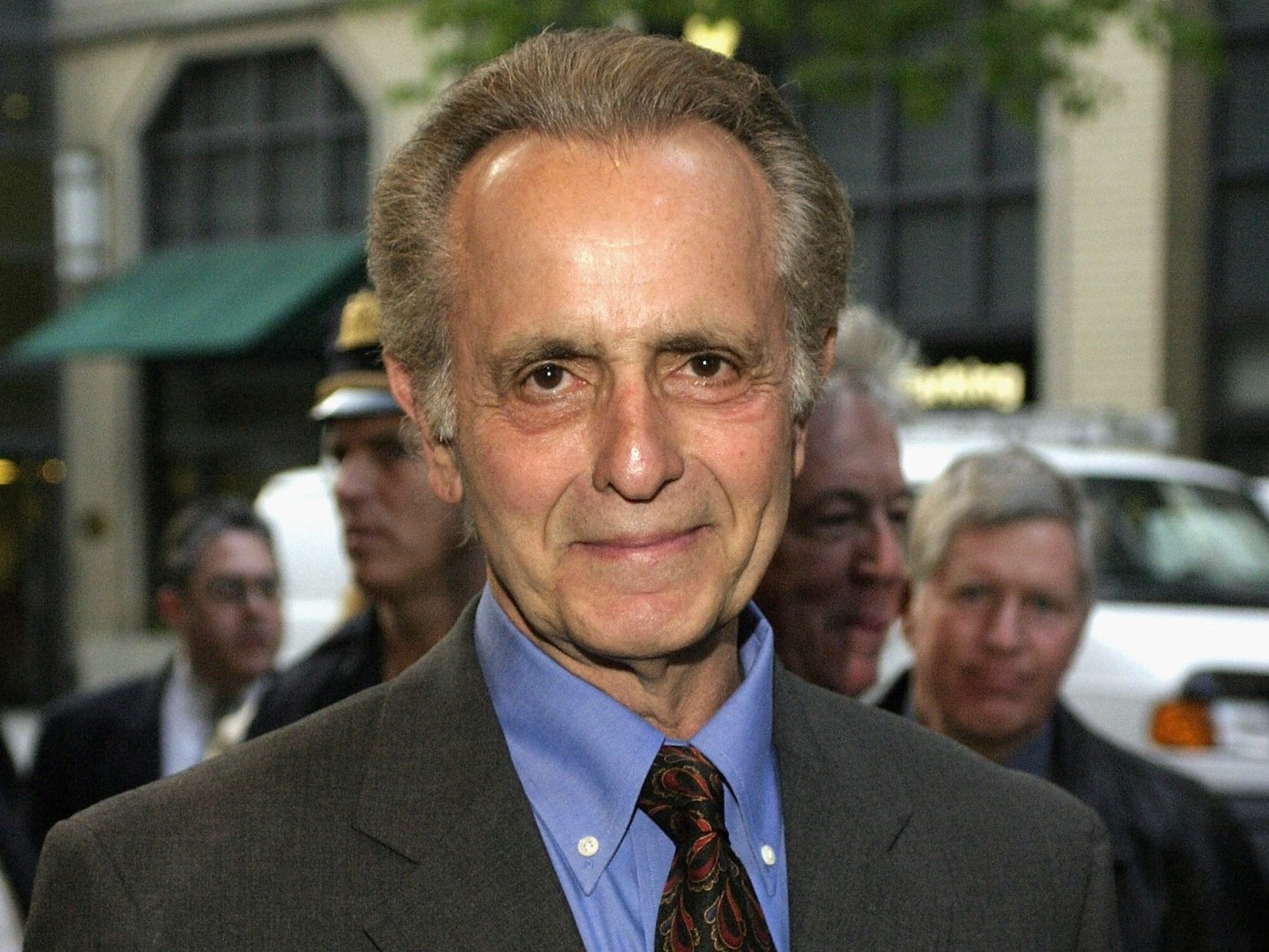

Mark Medoff: Tony-winning playwright of ‘Children of a Lesser God’

The provocative playwright, whose screen adaptation of his play about deafness was also nominated for an Oscar, penned more than two dozen plays

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mark Medoff, who helped bring unhearing characters and actors to Broadway in his play Children of a Lesser God, a vibrant portrait of deaf identity that earned him a Tony Award and an Oscar nomination after he helped adapt it into a hit film, died on 23 April at a hospice in Las Cruces, New Mexico. He was 79.

The death was confirmed by his manager, Brian Espinosa. Medoff had cancer and had recently suffered a fall, according to the Las Cruces Sun-News.

Medoff worked as a screenwriter, actor, director and theatre professor but was best known for his more than two dozen plays, which often featured witty, poetic language and undercurrents of violence.

His breakthrough, When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?, opened off-Broadway in 1973 and centred on a Vietnam War veteran who holds a New Mexico diner hostage. The play won Drama Desk and Obie awards for Medoff and the production’s stars, Kevin Conway and Elizabeth Sturges, and was adapted into a 1979 film with a screenplay by Medoff.

In a departure from that work’s brutal, drug-addled atmosphere, Marks then wrote Children of a Lesser God, a romantic drama about an idealistic speech therapist who falls in love with a deaf woman at his school. The play grew out of Medoff’s friendship with Phyllis Frelich, a deaf actress whom Medoff met at a drama workshop in 1978.

“She was so animated and vivid, she made me immediately want to be able to converse with her,” Medoff told The New York Times in 2014, for Frelich’s obituary. “I was swept away. Within 20 minutes I told her I was going to write her a play.”

Working with Frelich and her husband, Robert Steinberg, Medoff set about creating a play that would incorporate American Sign Language, dismantle some of the stereotypes surrounding deafness, and feature Frelich in a leading role – a departure from Broadway productions and films such as Johnny Belinda, in which deaf characters were played by hearing actors.

Taking its title from a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, Children of a Lesser God opened on Broadway in 1980, ran for 887 performances and won the Tony for best play, as well as acting honours for Frelich and her co-star, John Rubinstein. “Deafness isn’t the opposite of hearing, as you think,” Frelich’s character tells him at one point. “It’s a silence full of sounds.”

Some critics saw the work as melodramatic and derivative, part of a wave of inspirational “disability plays” that included Whose Life Is It Anyway?, about a paralysed sculptor. For the most part, however, the production was met with acclaim and reverence, seen as groundbreaking for its accessibility for deaf and hearing viewers. (Rubinstein speaks most of Frelich’s signed lines, effectively taking on two roles.)

“What makes Medoff’s play so shrewd and moving,” wrote Newsweek drama critic Jack Kroll, “is that his compassion is not for those who cannot hear sounds, but for those who cannot hear the chords of communication between people, and in this we are all hard of hearing, as well as partially blind, numb of touch, with fast-food taste buds and stuffy noses.”

A 1981 London production received the Society of West End Theatre Award – now known as the Olivier Award – for best play, and the work was briefly revived on Broadway in 2018. When it was adapted into a film in 1986, it marked the first major movie about deafness since The Miracle Worker (1962).

The film featured a screenplay by Medoff and Hesper Anderson, and starred William Hurt and deaf actress Marlee Matlin, who at 21 years old became the youngest person to win the Oscar for Best Actress, and the first deaf performer to win an Academy Award.

“Deaf people are like hearing people – they all have different opinions about the movie,” Kevin Nolan, a guidance counsellor at the Clark School for the Deaf in Massachusetts, said upon its release. “But the movie is still a very important work for the deaf because it educates the hearing. Hearing people still have so many misconceptions – like deaf people can’t read or dance or cry or laugh. The movie shows that we have the same worries and feelings, abilities and aspirations as anyone else.”

In a tweet on Thursday, Matlin said that Medoff “insisted and fought the studio” so that a deaf actress could star. She added, “I would not be here as an Oscar winner if it weren’t for him.”

Mark Howard Medoff was born in Mount Carmel, Illinois, on 18 March 1940, and raised in Miami Beach. His mother was a therapist, and Medoff said he was planning to follow his father into medicine when a high school English teacher told him he had literary talent.

Asked to read his short story in front of the class, Medoff later recalled having a moment’s hesitation, writing in a 1986 New York Times essay that he was encouraged by a look from his teacher that said, “Don’t be afraid of anything.”

“So I go forward,” he added, “take my story from him, and in the space of 20 minutes of inimitable glory and befuddlement, write a sentence across my life: Mark Medoff, you are hereby condemned, for the rest of your days, to expose your secret self publicly.”

Medoff graduated from the University of Miami in 1962 and, after receiving a master’s degree in English from Stanford University in 1966, he began teaching at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. Initially, he told People magazine, he was a hostile and unhappy colleague, so depressed by the desert campus that he drove home to Florida, where his parents persuaded him to return to the university.

He had planned to write novels in his spare time, but at the suggestion of a colleague, he wrote his first play, a one-act called The Wager. In 1974, it opened at the Eastside Playhouse in Manhattan in expanded form, leading New York Times reviewer Clive Barnes to hail Medoff as “a dexterous and extraordinarily witty playwright”.

Early in his career, Medoff reportedly punched the wall or kicked his television while struggling with a piece of writing. But Children of a Lesser God exerted a soothing effect; he told The Washington Post in 1981 that during its creation he “became more humane in terms of attitudes towards the people I was writing about” and developed warmer relationships with his professional colleagues.

He remained at NMSU for more than 50 years, during which he co-founded the school’s American Southwest Theatre Company and elevated the Las Cruces theatre scene. At a school drama camp, he discovered a teenage Neil Patrick Harris, whom he cast in the 1988 film Clara’s Heart, an adaptation of a Joseph Olshan novel with a screenplay by Medoff.

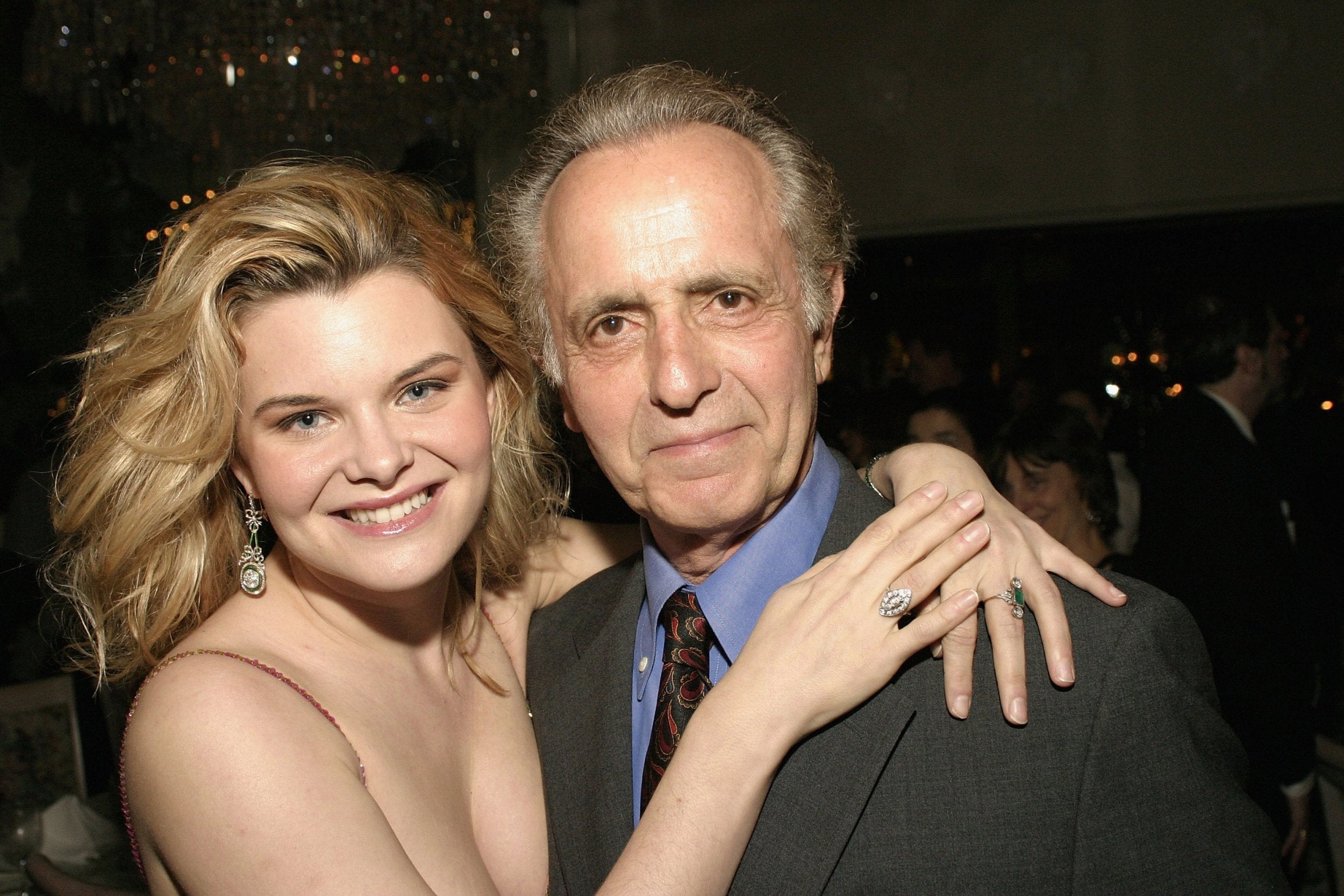

He also directed several independent films – including Children on Their Birthdays (2002), based on a short story by Truman Capote – and continued collaborating with Frelich. She starred as a deaf anthropologist who teaches ASL to a gorilla in his play Prymate, which marked Medoff’s Broadway return when it premiered in 2004 to disastrous reviews.

Medoff’s first marriage, to Vicki Eisler, ended in divorce. In 1972 he married Stephanie Thorne, a former student. In addition to his wife, survivors include three daughters from his second marriage and eight grandchildren. With his family, he created the Hope E Harrison Foundation to support research into the chromosomal abnormality Trisomy 18, which affects one of his granddaughters.

Medoff often spoke of the central role teaching held in his life, and of the influence teachers had on him. In 1986, he recalled an episode in which he reunited at age 35 with one of his high school English teachers and struggled to find the right words to thank her for her encouragement. “I want you to know you were important to me,” he said, before she began to weep and embrace him.

“Remembering the moment, I have a sense at last of this,” he wrote. “Everything I will ever know, everything I will ever pass on to my students, to my children, to the people who see my plays is an inseparable part of an ongoing legacy of our shared frailty and curiosity and fear – of our shared wonder at the peculiar predicament in which we find ourselves, of our infernal and eternal hope that we can, must, make ourselves better.”

Mark Medoff, playwright, writer and educator, born 18 March 1940, died 23 April 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments