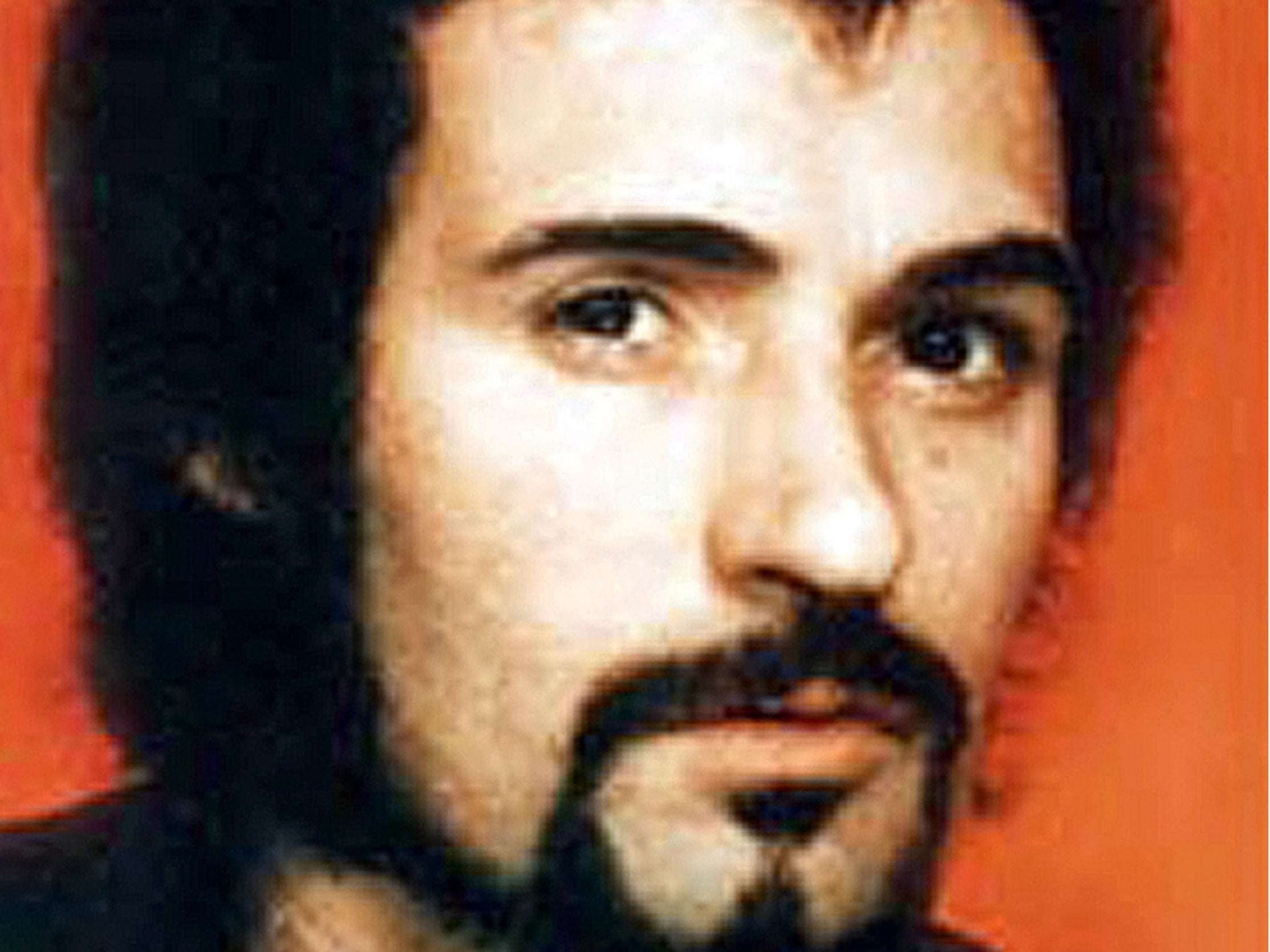

Yorkshire Ripper: Wearside Jack hoax and police blunders that derailed inquiry

Despite the 2.5-million police man hours expended on catching him, Peter Sutcliffe continued his murderous spree for more than five years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper became the biggest manhunt Britain had ever known, but it was dogged by police blunders and the Wearside Jack hoax.

Despite 2.5-million police man hours expended on catching him, Peter Sutcliffe continued his murderous spree for more than five years.

During the police inquiry he was interviewed nine times, but was only caught when picked up by chance with a sex worker in his car.

He eventually attacked 20 women, killing 13 of them, between 1975 and 1980.

A series of spectacular police blunders left even Sutcliffe amazed that he had not been caught before.

At his Old Bailey trial he said: "It was just a miracle they did not apprehend me earlier — they had all the facts."

The inquiry was further confounded by one of criminal history's cruellest hoaxes: John Humble tricked police into believing the serial killer was Wearside Jack, a man with a gruff Sunderland accent.

That was despite women who survived Peter Sutcliffe's attacks saying he sounded like a local.

Humble, for reasons he never fully explained, delighted in taunting the press and detectives with letters and an infamous tape, anonymously claiming he was the killer who was terrifying northern England in the late 1970s.

He sent it to assistant chief constable George Oldfield in 1979, saying: "I'm Jack.

"I have the greatest respect for you, George, but Lord, you're no nearer catching me now than four years ago when I started."

The ruse hijacked the already-cumbersome police inquiry and diverted resources from the streets of Yorkshire and the North West to Wearside.

The tape and letters convinced officers because they included details which police, wrongly, believed had never been made public.

Though Sutcliffe had been questioned by police, his handwriting did not match that in the hoaxer's letters.

As well as Humble’s cruel hoax, police were inundated with information about Sutcliffe.

The Ripper incident room at Millgarth police station used a card-index system, which was overwhelmed with information and not properly cross-referenced, leading to evidence against Sutcliffe getting lost in the system.

Crucial similarities between him and the suspect, like the gap in his teeth and his size seven feet, were not picked up.

As early as 1976, when Marcella Claxton was hit over the head with a hammer near her home in Leeds, potentially vital evidence was overlooked.

She survived the attack and was able to help police produce a photofit — which later proved to be accurate — but she was discounted as a Ripper victim because she was not a sex worker.

On one occasion, Sutcliffe was interviewed by officers who showed him a picture of the Ripper's bootprint near a body — they failed to notice that Sutcliffe was wearing the exact same pair of boots.

When a £5 note was found in the pocket of 28-year-old Jean Jordan, in Manchester in 1977, police again failed to connect Sutcliffe.

The note was traced to one of six companies, including Clark Transport, which employed Sutcliffe as a lorry driver.

He was interviewed but was given an alibi by his wife and mother, which was accepted.

Police also overlooked Sutcliffe's arrest in 1969 for carrying a hammer in a red light district, and attempts by his friend Trevor Birdsall to point the finger at him in a anonymous letter.

But the worst blunder came in 1979, when Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield of West Yorkshire Police , who was in overall command of the hunt, was hoodwinked by Wearside Jack.

There were warnings of a hoax from voice experts and other detectives, but Oldfield pressed on, convinced this was his man.

Because the voice on the tape had a North East accent, Sutcliffe, who was from Bradford, was not in the frame.

Oldfield's mistake has been described as one of the biggest in British criminal history, but he was widely regarded as a "top-notch copper".

An "old school" policeman with three decades experience, he was a hard drinking, dedicated man who developed a deep personal obsession with nailing the Ripper.

He worked 18-hour days and made a personal pledge to the parents of the sixth victim, Jayne MacDonald, that he would catch the killer.

His 200-strong ripper squad eventually carried out more than 130,000 interviews, visited more than 23,000 homes and checked 150,000 cars.

Later the same year Oldfield had a heart attack at the age of 57, and was subsequently moved off the case.

He has been described by friends as "the Ripper's 14th victim".

With attention focused on suspects with a North East accent, the Ripper continued his killing spree and claimed his 13th and last murder victim, 21-year-old student Jacqueline Hill, late in 1980.

At that time police had a league table of suspects.

There were 26 in Division One — at the top was a completely innocent taxi driver who they tailed for months.

Some 200 names were in Division Two and 1,000 — including Sutcliffe — were in Division Three.

Then, in January 1981, police finally got some luck when Sutcliffe was arrested by officers in Sheffield, who stopped him with a sex worker in his brown Rover car.

The car had false number plates and Sutcliffe's name was passed on to the Ripper squad, where it came up on their index cards.

He had always denied any involvement with sex workers in his previous interviews, and they decided to talk to him again.

The officers who went to Dewsbury police station to interview him looked at the car and found screwdrivers in the glove compartment.

The Sheffield officers, meanwhile, hearing Sutcliffe was a Ripper suspect, went back to the scene of his arrest and found a hammer and knife 50ft from where his car had been.

Sutcliffe had dumped the weapons when they allowed him to go to the toilet at the side of a building.

Police also visited Sutcliffe's wife Sonia, who admitted he had not got home until 10pm on Bonfire Night, when a 16-year-old girl was attacked.

As the net closed, Sutcliffe suddenly and unexpectedly confessed.

He calmly told Detective Inspector John Boyle, who was interviewing him : "It's all right, I know what you're leading up to. The Yorkshire Ripper. It's me. I killed all those women."

He then began a detailed confession lasting 24 hours, and asked for Sonia to be brought in so he could tell her personally that he was the Ripper.

Sutcliffe went on trial at the Old Bailey in May 1981, where he claimed he had been directed by God to kill prostitutes.

The jury had to decide whether, at the time of the killings, he believed he was carrying out a divine mission.

After lengthy deliberations they returned a 10-2 majority verdict of guilty and was jailed for life.

The case remains one of the most notorious of the last 100 years and the assessment of what went wrong in the investigation is still having an impact on major police inquiries to this day.

The Wearside Jack messages were finally, conclusively proved to be hoax nearly 30 years after they were sent when Sunderland alcoholic John Humble admitted perverting the course of justice and was jailed for eight years in 2006.

It emerged that Humble had a grudge against police as a youth and an interest in the Jack the Ripper story.

But he had felt guilt when the Ripper continued to kill after the tape arrived, telling police: "I blamed myself for it. That's why I phoned in.

"They took no notice and another two got killed."

During Humble's case, it emerged that Sutcliffe had told police how the Wearside Jack hoax had helped him.

The killer said: "While ever that was going on, I felt safe.

"I'm not a Geordie. I was born at Shipley."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments