The jungle prince of New Delhi

In a forest palace cut off from the city that surrounds it, lived a prince, a princess and a queen, said to be the last of the Shia Muslim royals. Ellen Barry on the trail of one of Delhi's greatest mysteries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a spring afternoon in 2016, when I was working in India, I received a telephone message from a recluse who lived in a forest in the middle of Delhi. I knew about the royal family of Oudh. They were one of the city’s great mysteries. Their story was passed between tea sellers and rickshaw drivers and shopkeepers in Old Delhi: in a forest, they said, in a palace cut off from the city that surrounds it, lived a prince, a princess and a queen, said to be the last of a storied Shia Muslim royal line.

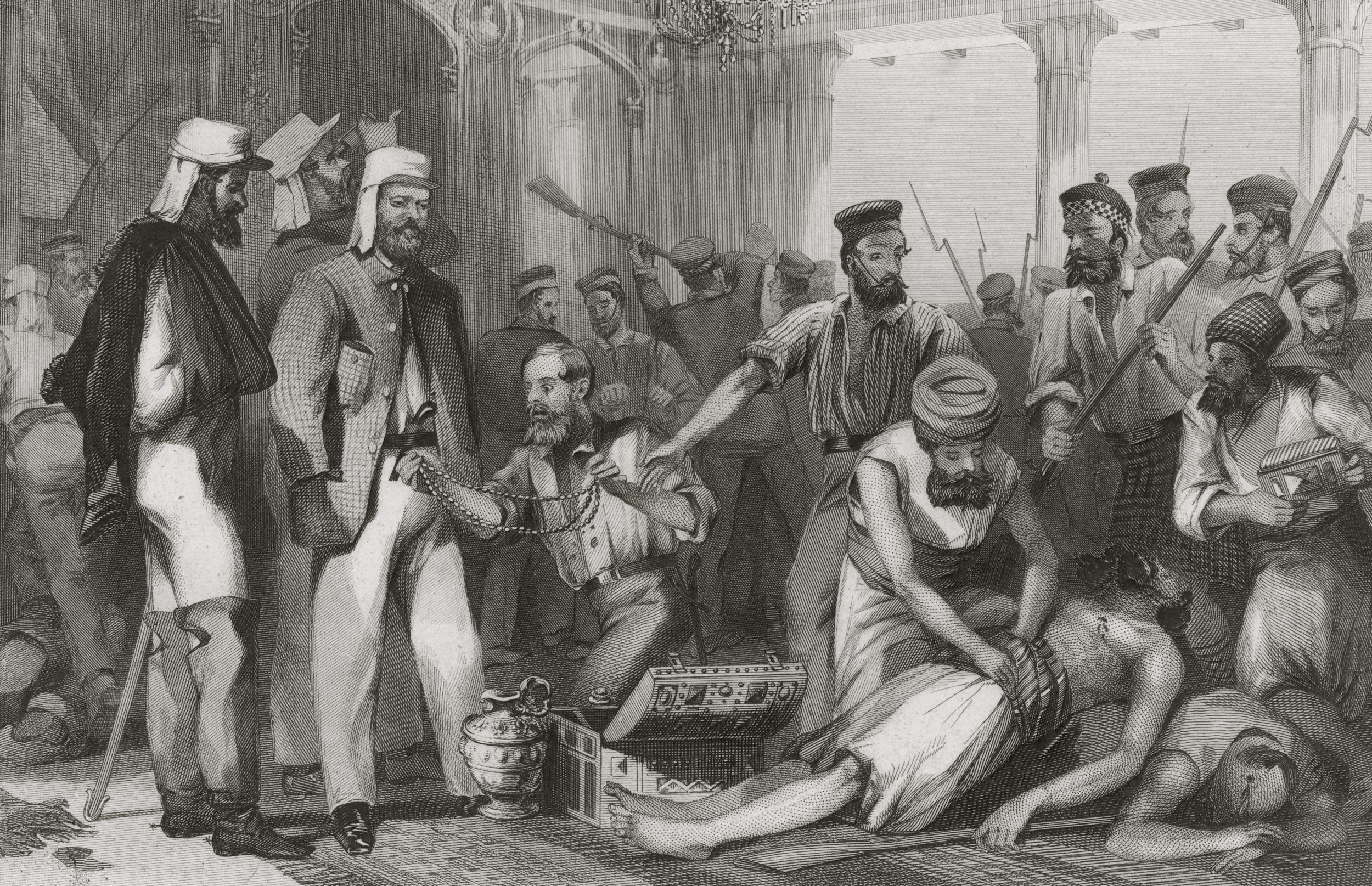

There were different versions, depending on whom you spoke to. Some people said the Oudh family had been there since the British had annexed their kingdom in 1856, and that the forest had grown up around the palace, engulfing it. Some said they were a family of jinns, the supernatural beings of Arabian folklore.

One thing was sure: they didn’t want company. They lived in a 14th-century hunting lodge, which they surrounded with loops of razor wire and ferocious dogs. But, every few years, the family agreed to admit a journalist, always a foreigner, to tell of their grievances against the state. The journalists emerged with deliciously macabre stories. In 1997, the prince and the princess told The Times that their mother, in a final gesture of protest against the treachery of Britain and India, had killed herself by drinking a poison mixed with crushed diamonds and pearls.

I could see why these stories resonated. The country was imprinted with trauma, by the epic deceit of the British conquest, and then the bloodbath of the British departure, known as partition, which carved out Pakistan from India and set off convulsions of Hindu-Muslim violence.

This family, displaying its own ruin, was a physical representation of all that India had suffered. The day after I got the message, I dialled the phone number. After a few rings, someone picked up, and I heard a high-pitched, quavering voice on the other end. On the following Monday, I asked our driver to take me into the woods at 5.30 in the afternoon, as instructed.

The person on the phone had told me to leave the car at the end of the road, and to come alone. This did not surprise me: the Oudh family refused, famously, to meet Indians. I asked the driver to wait at a distance and stood in the woods, somewhat awkwardly, holding my notebook and wondering what came next.

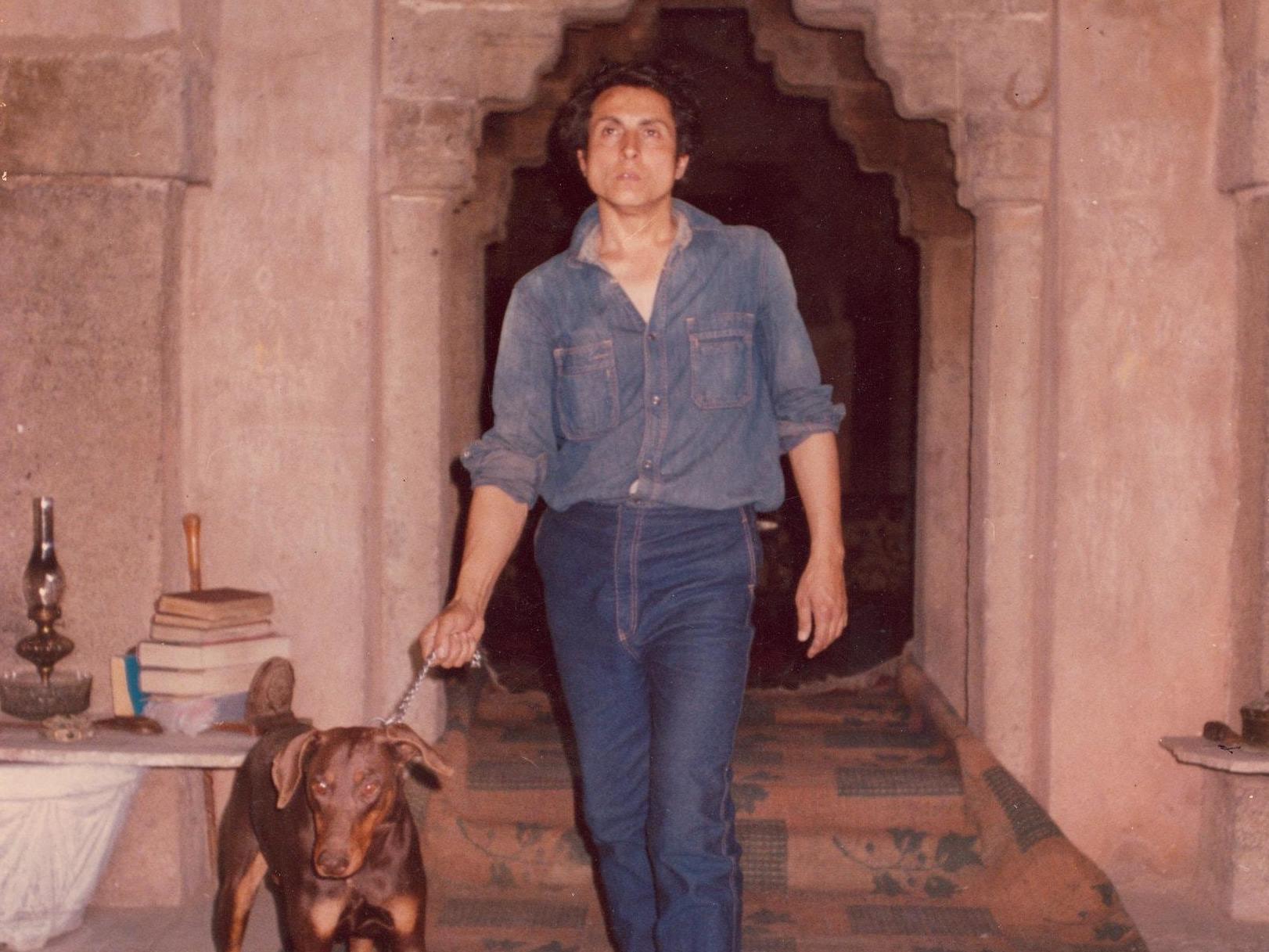

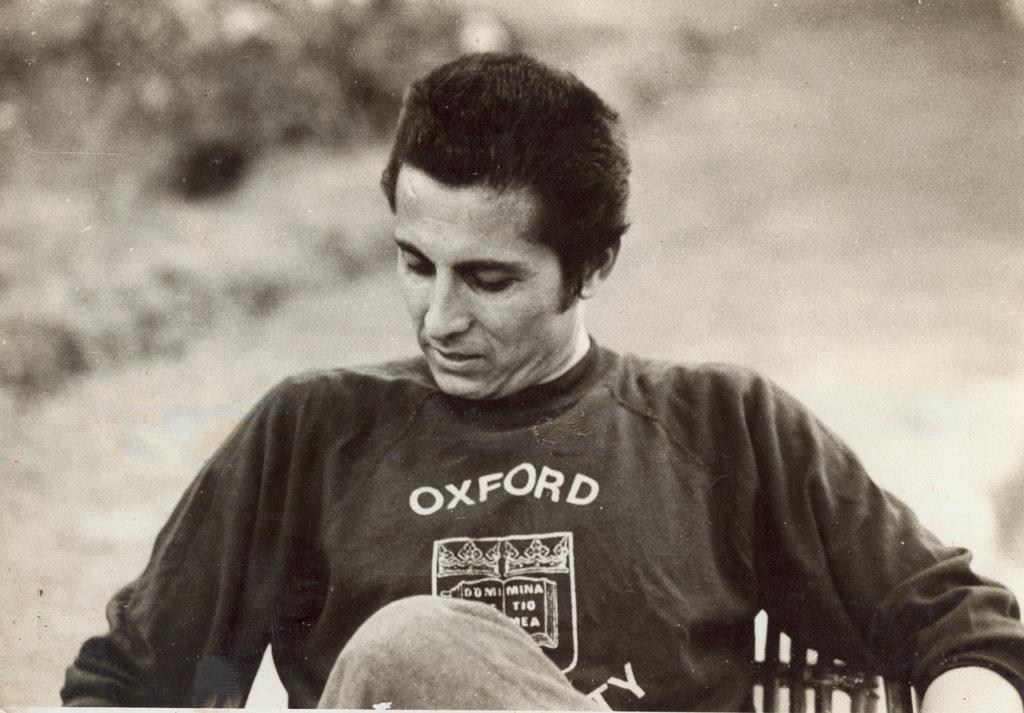

Then the bushes rustled, and a man appeared. He was elfin and wore high-waisted jeans. He had high cheekbones with hollows beneath them and wild grey hair that stood up in tufts. “I am Cyrus,” the prince said. It was the high-pitched voice I had heard on the phone. He spoke in bursts, like a person who spent most of his time alone. Then he turned and led me into the woods. I tried to keep up, stepping over a tangle of roots and thorns, and climbed a flight of massive stone stairs leading to the old hunting lodge. It was half-ruined, open to the air, and surrounded by metal gratings.

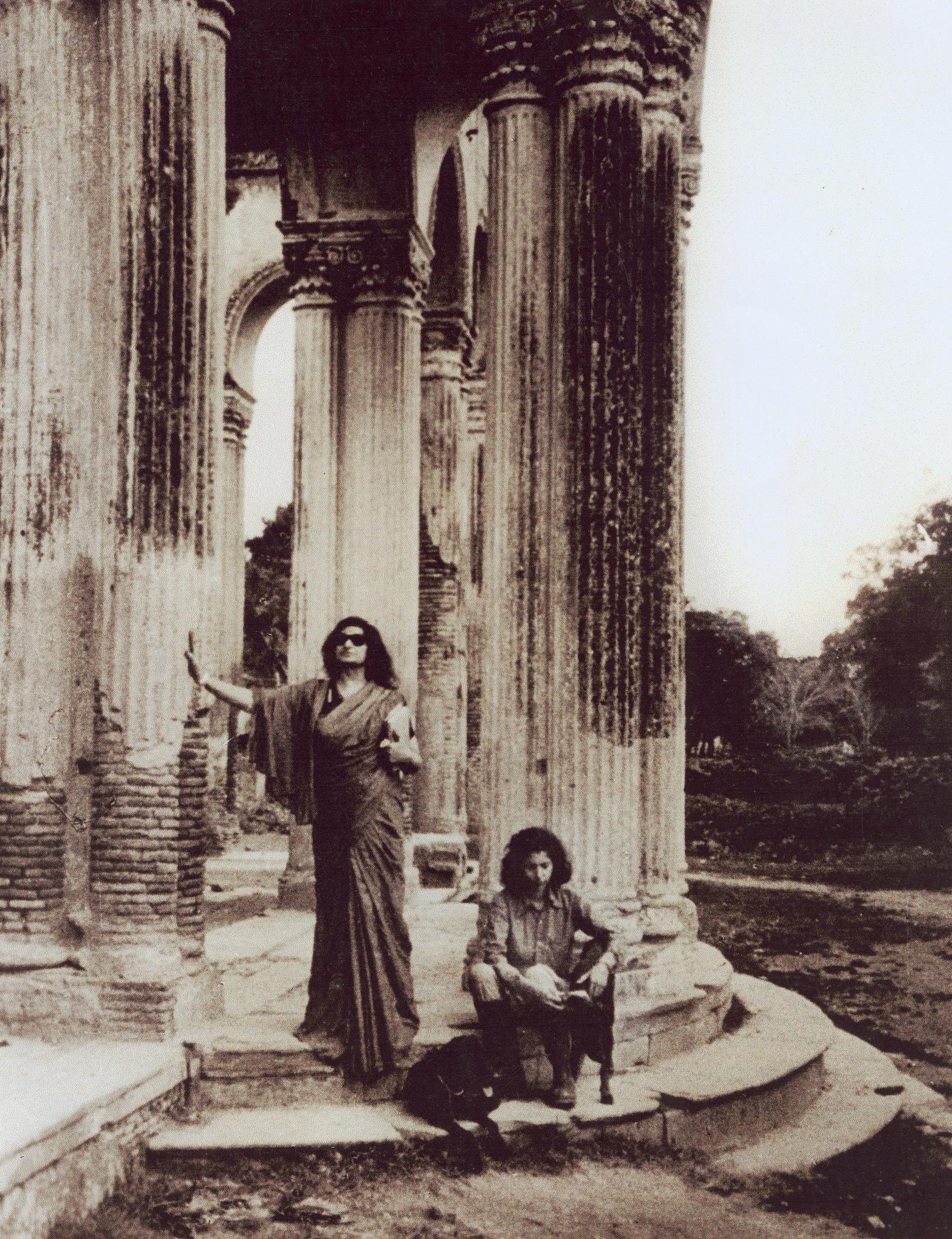

I stepped into spare, medieval grandeur, a bare stone antechamber lined with palm trees in brass pots and faded, once-elegant carpets. On the wall hung an oil painting of the prince’s mother swathed in voluminous, dark robes, her eyes closed as if in a trance. My idea was to interview the prince and write the story. When I asked about his family, he launched into an animated speech about the perfidy of the British and Indian governments.

“I am shrinking,” he said. “We are shrinking. The princess is shrinking. We are shrinking.”

When I asked if I could publish our interview, he balked. For this, he said, I would need the permission of his sister, Princess Sakina, who was not in Delhi. I would have to come back. The story began with his mother. She appeared, on the platform of New Delhi’s train station in the early 1970s, seemingly from nowhere, announcing herself as Wilayat, Begum of Oudh.

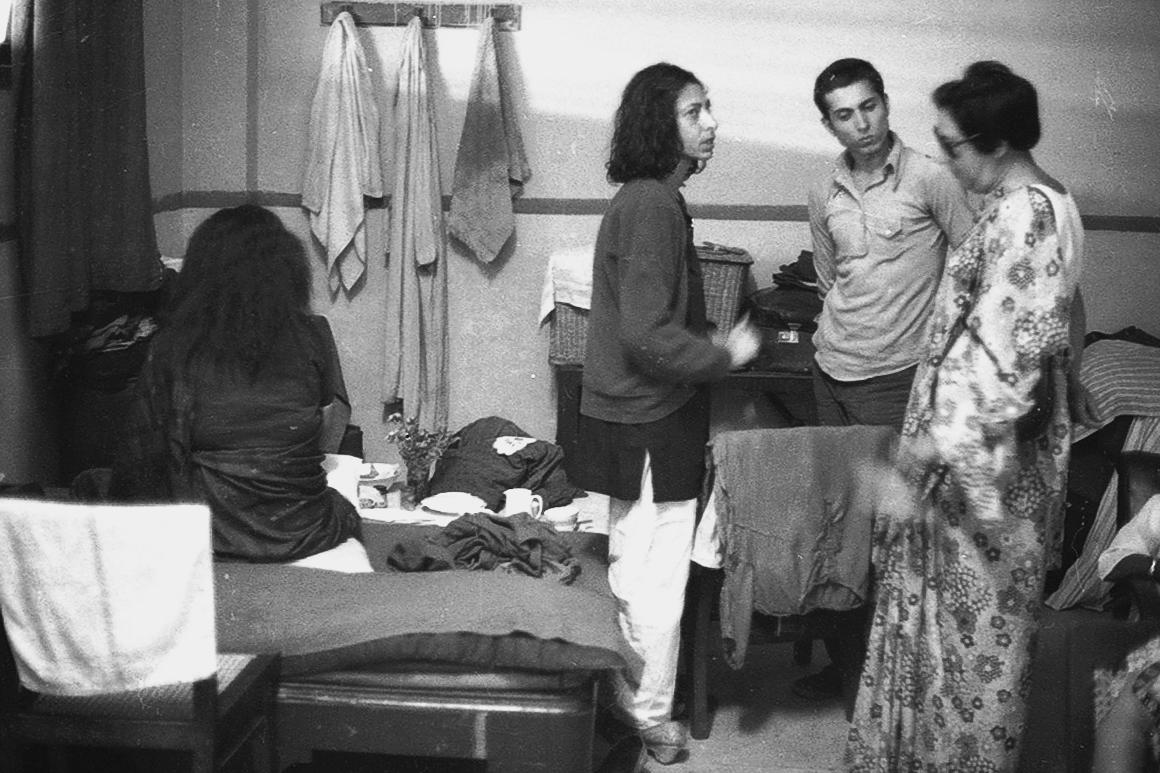

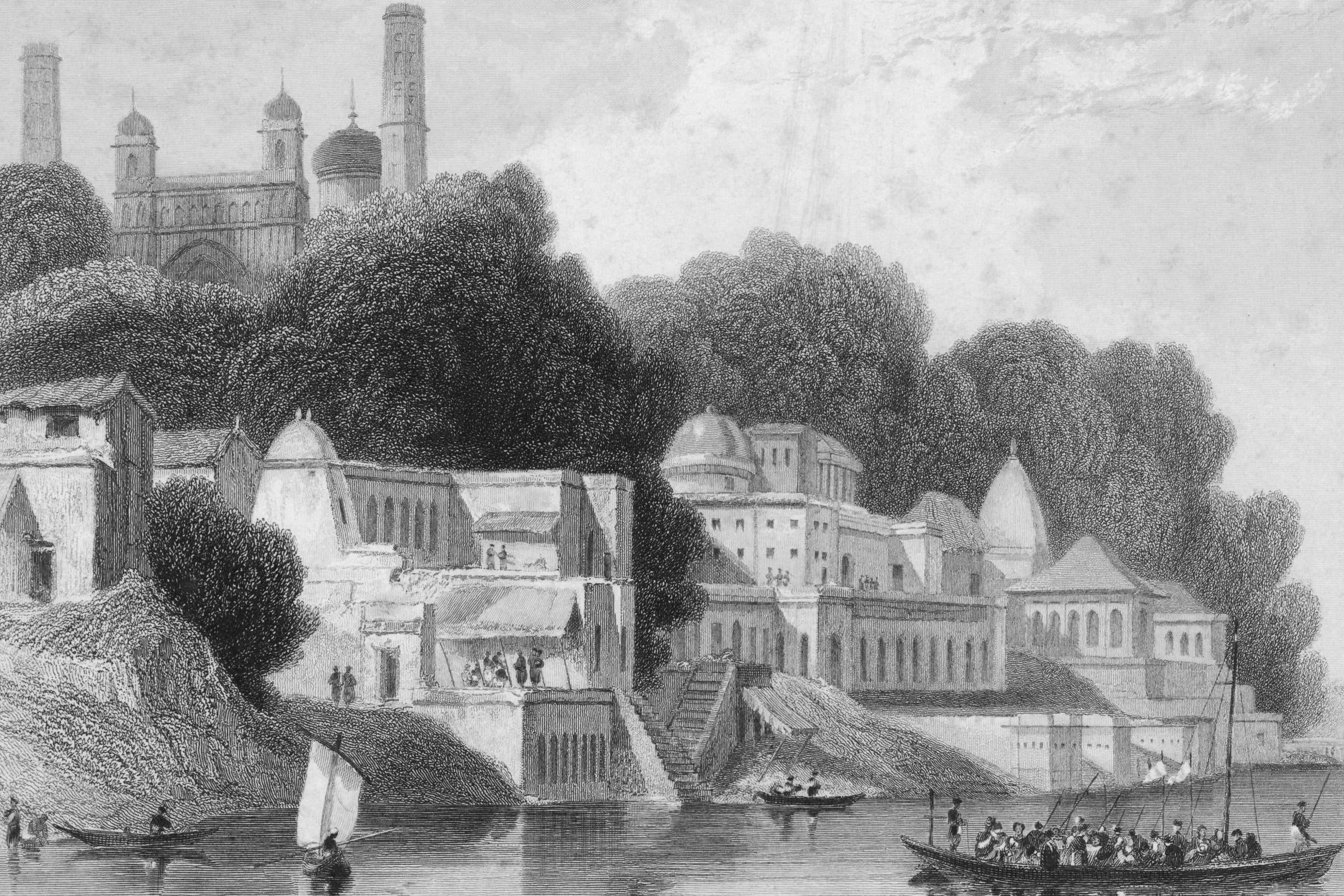

Oudh (pronounced Uh-vud) was a kingdom that no longer existed. The British annexed it in 1856, a trauma from which its capital, Lucknow, never recovered. The core of the city is still made of Oudh’s vaulted shrines and palaces. The begum declared that she would stay in the station until these properties had been restored to her. She settled in the VIP waiting room, and unloaded a whole household there: carpets, potted palms, a silver tea set, Nepali servants in livery, glossy great danes. She also had two grown children, Prince Ali Raza and Princess Sakina, a son and a daughter who appeared to be in their twenties. They addressed her as “Your Highness”.

Foreign correspondents arrived, one after another, and readers began to send letters from all corners of the world, expressing outrage on her behalf. The begum imposed stringent conditions – she “could only be photographed when the moon was waning”, United Press International reported – and journalists complied, delighted with the Gothic peculiarity of it all.

In 1984, her efforts paid off. The prime minister, Indira Gandhi, accepted their claim, granting them use of a 14th-century hunting lodge known as Malcha Mahal. They left the train station roughly a decade after they first appeared there. Wilayat never appeared in public again.

When our conversations had gone on for about nine months, I travelled to Lucknow, a large city in northern India that was the cradle of the Oudh dynasty. I was there for an unrelated story, but I knew that Cyrus had lived there with his mother and sister in the 1970s, so I went to the neighbourhood where I had heard that Oudh descendants lived.

There, to my surprise, the old-timers remembered Cyrus and his family. But they told me, almost as an aside, that they had been dismissed as impostors. The Oudh descendants in Kolkata, where the nawab died in exile, had also rejected their claim. And there were questions Cyrus himself seemed unable to answer. Where was he born? Who was his father? How do you crush diamonds, anyway?

One night Cyrus called me, howling unintelligibly, to tell me that his sister had in fact died seven months earlier. He had told no one, burying her body himself. He had lied to me about it for months, and seemed a bit ashamed by it. He said that I should never visit again, and also that he was so lonely.

I waited a few days, and then showed up with a Filet-O-Fish from McDonald’s. Our relationship seemed to knit itself back together. He even said I could write something about him, as long as I didn’t go into much detail. “I have to tell the truth,” I told him.

“OK, you have to tell the truth,” he said.

We had been debating this for 15 months, and I was due to leave India soon and take up a new assignment. This sort of exchange made up the balance of our final conversations: I was trying to get him to reveal something about his origins – anything, really – and he was twisting away from me.

In our last conversation, a few hours before I boarded a flight for London, he asked me how someone could get word to me, should he die. I asked if he planned to kill himself.

“So far, I am going to preserve myself,” he said.

“Good. Well, then, I’ll see you again,” I said.

I think I hugged him goodbye; that was the last I saw of him. Three months later, I was in an airport when I learned Cyrus had died. I got the news on Facebook messenger, from a friend at the BBC. It was the guards at the military facility next door – they called him “rajah”, or king – who later recounted how he had died. One of the guards said it seemed to be dengue fever.

I climbed the stone stairs to Malcha Mahal several months later with a kind of curiosity that was in some ways like greed. I had returned to India for a few days to see what I could find among his possessions. I leafed through the letters, looking for a birth certificate, a passport, something that anchored this family in the factual world.

Two things genuinely surprised me. The first was a stack of receipts for regular, small transfers of cash through Western Union from a city in the industrial north of England. The sender identified himself as a “half brother”.

The other thing was a letter. It was handwritten and sent in 2006. It was cranky yet intimate, conveying both annoyance and concern. “I am in so much pain that I cannot go to the toilet even,” the writer began, and, after an extensive catalogue of physical ailments, went on to complain about the burden of providing continuous financial support for Wilayat and her children. He was obviously not a rich man.

“For God’s sake, try to sort yourselves out financially, in case anything goes wrong with me,” the writer told them, appending information for the latest Western Union transfer. “May God help us all.”

The letter was signed “Shahid”, and it was sent from an address in Bradford, Yorkshire. I returned to London with three real leads. The airmail letter from Yorkshire. That name, Shahid. The Western Union receipts, testament that someone had been caring for Cyrus and his family in secret all these years.

I took a train to Bradford, and walked to the address on the envelope. I arrived at a small, neat brick house that was surrounded by a large collection of ceramic garden gnomes, teddy bears, Yorkies, mermaids and fairies.

The door swung open, and before me stood a man in tiger-print pajamas. He was barrel-chested and broad-shouldered, and looked to be in his mid-eighties. He did not look well: his eyes were rheumy, his chest sunken.

But he had Cyrus’s face, the same jutting cheekbones and hawk nose.

He led me inside, showed me to a chair and then lay down on a cot. His movements were laborious. He glanced without expression at the photographs I had brought with me. When I offered to play him a recording of Cyrus’s voice, he shook his head in refusal, saying it would be too painful.

Beside his sickbed were two framed pictures of Wilayat. This was Shahid. He was Cyrus’s older brother. And now, finally, there were some facts. They were, or had been, an ordinary family.

Their father had been the registrar of Lucknow University, Inayatullah Butt. My friend’s name was not Prince Cyrus, or Prince Ali Raza, or Prince anything. He was plain old Mickey Butt.

Here, in this brick house in West Yorkshire, I had found it: the identity that Cyrus and his family had worked so hard to keep secret. Shahid, who spent his adult life working in an iron foundry, could remember a life before Oudh, when they had housemaids and school uniforms. When their mother was not a rebel queen, but a housewife.

Shahid ran away when he was about 14, then emigrated to Britain and rarely mentioned his mother’s claim to the royal house of Oudh. When I asked him about that story, he was evasive. He said he wasn’t even sure whether he was Indian or Pakistani.

“I’m so confused, I don’t know who I am,” he said. “I am like a bird, a long-lost bird, a lost lamb.”

Trying to get Shahid to speak about his mother and siblings was painful.

On my fourth visit to Bradford, the last time I saw him, his voice was raspy, but he told me more than he ever had before.

The story, as he told it, began with partition. On 3 June 1947, the British viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, announced that the withdrawal of British empire would create two independent nations, with Pakistan carved out for Muslims. Lucknow’s educated Muslims began slipping away overnight, headed for Pakistan’s new capital. There were letters promising juicy promotions. And there were, on the other hand, rumours of violence if they stayed.

Shahid’s parents had to make an immediate decision between India and Pakistan. His mother, Wilayat Butt, had never been so happy as she was in Lucknow. She was fiery and strong. She simply refused to leave. But then came one afternoon in the crumbling elegance of the nawab’s city. Shahid’s father – a man in distinguished middle age, wearing wire-rimmed glasses – was riding his bicycle home when he was surrounded by Hindu youths, who began beating him with hockey sticks.

He soon decided to move the whole family to Pakistan, where, in the great reshuffling, he had been offered a job overseeing the new country’s civil aviation agency.

Wilayat followed her husband, Shahid told me, but she never accepted his decision to leave India. She was obsessed with what she had left behind. In her mind, the grudge sprouted and germinated, and her behaviour became volatile. Then her husband suddenly died. Now with all restraining influence on her gone, furious over the expropriation of her property, she accosted Pakistan’s prime minister at a public appearance, Shahid said, and slapped him.

This changed things for Wilayat. She was no longer a well-connected widow, but something shadier.

She was confined to a mental hospital in Lahore for six months after that – the only way, Shahid said, to avoid a long prison sentence. Shahid remembers visiting her there, among the wails and curses of the patients. “It was horrible,” he said.

When she was free, Wilayat gathered up her youngest children, packed trunks with carpets and jewellery, and smuggled it all back into India, with the goal of reclaiming her property. Shahid set out with them but eventually walked away. He could not put into words why he left. His story flickers out here.

Early this month, Shahid died in the front room of his house, holding his wife’s hand. It was partition that ruined his mother, set her on the course towards the ruined palace, Shahid had told me. “We had to start all over again,” he said.

In the early 1970s, still empty-handed, increasingly bizarre in her behaviour, Wilayat announced to the world that she was the queen of Oudh, demanding the vast properties of a kingdom that no longer existed.

An ordinary grievance, unaddressed, had metastasised to become an epic one.

The rest of the story you already know. They were so convincing, and so insistent, that for 40 years people believed them. So there it is: I have plundered their secret. Cyrus would have hated it. He refused to answer questions about his past; it was one of the essential themes of our friendship. I try to imagine how he would react to all this. And yet, why do you invite a journalist into your life, if you do not expect this to happen?

He had been buried in a public cemetery as an unclaimed body, assigned the number DD33B. Unclaimed bodies are marked only with chips of stone, and small mounds extend in all directions, to the vanishing point. After wandering the cemetery for what seemed like hours, I sat down, sweaty and miserable.

“He is lost in a city of the dead,” I wrote in my notebook.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments