A History of the First World War in 100 moments: After 1,560 days, at the eleventh hour, the guns fall silent – but for how long?

The conclusion of the ‘war to end all wars’ was greeted with understandable jubilation. But, writes Boyd Tonkin, new storm clouds were already gathering

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Five times decorated for bravery, the corporal of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry learnt about Germany’s defeat while convalescing in a military hospital at Pasewalk in Pomerania. A month beforehand, the British had gassed his regiment at Ypres.

One doctor at least thought that the intermittent blindness his patient suffered had a hysterical origin. The mettle of this soldier was beyond dispute. He had received his Iron Cross, First Class (most uncommon for an NCO) from another rare bird: First Lieutenant Hugo Guttmann, a Jewish officer. But the casualty appeared slovenly, truculent, highly strung – an artist of some kind. After he heard the news, after swirling rumours of rebellion and what he called “something indefinite but repulsive in the air”, he wept into his private darkness. “I had not cried since the day I stood at my mother’s grave,” Gefreiter Adolf Hitler would later write. “Now I could not help it.”

By 11 November 1918, most combatants and civilians had for three or four days rehearsed and anticipated the end of the Great War. As early as 5 October, the German High Command sent a note to Woodrow Wilson suing for peace on the basis of the US President’s “Fourteen Points”. On 4 November, the Kiel naval mutiny demonstrated to the Allies that the German forces would no longer obey the Kaiser and his generals. Red revolution spread across the Reich. On 9 November, Wilhelm II abdicated at Spa – or, to be exact, he was abdicated. Impatient of the emperor’s last-ditch vacillations, Germany’s new liberal Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, on his own initiative issued the most momentous pre-emptive press release in history, via the Wolff agency, announcing – though he had not yet done so – that the Kaiser had stepped down as both Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia. “It’s a shameless betrayal,” stormed the ex-Kaiser, a picture of impotence. Premature jubilations had already broken out in Britain, France and the US on 7 November, when the French intelligence service somehow took the initiation of negotiations at Compiègne as proof of their conclusion, and sent out a gun-jumping message.

At 11am on 11 November 1918, it really would be all over. “Hostilities will cease on the whole front,” Marshal Foch’s signal told his forces. “The Allied troops will not, until further order, go beyond the line reached on that date and at that hour.” In theory, the armistice would hold for 36 days and could be rescinded if its terms were violated. Between 2.10am and 5.12am on the 1,560th day of conflict, a final bleary-eyed session in Foch’s dining-car had settled the terms of the armistice and of the German capitulation. Centre Party leader Matthias Erzberger, who led the German delegation, had managed to wring a couple of minor concessions from the victorious Allies – such as an acceptance that the vanquished Reich could not actually surrender 2,000 aircraft since it not possess 2,000 aircraft. Erzberger put on the bravest face he could, proclaiming that “a nation of 70 million people suffers, but it does not die”. By around 5.45am, most field commanders had learned of the terms and the timetable.

However, this most vicious of all wars kept a savage sting in reserve for the tip of its tail. The final six hours of fighting on the Western Front present a spectacle of futile bloodshed and pointless aggression that somehow sums up the whole show. Orders born of unfathomable malice or (more likely) benumbed habit insisted that assaults and advances must continue up to the eleventh hour. US General John (“Black Jack”) Pershing, in command of 1,200,000 troops in full cry around the Meuse-Argonne front, regretfully said: “What an enormous difference a few more days would have made.” Gung-ho Pershing hankered to overrun terrain that Germany had already agreed to yield.

So, in one scarred salient after another, the farewell push took its needless toll. The Hindenburg Line had already buckled and broken. Yet military logic demanded further punctures, up to the bitter end. Even the official history of the US 33rd Division, whose units attacked Butgneville, admitted that its troops considered “the loss of American lives that morning as useless and little short of murder”. After all, the officers did have a choice. Out of 16 commanders of US divisions who received early-morning news of the armistice, seven chose to stop fighting. But nine pressed on through blood, right down to the wire.

The crossing of the Meuse alone that morning cost the Americans 1,130 casualties. One German shell fired at 10.55am killed a US soldier who, in his dying words, told his lieutenant that “you know we all expected things to cease today”. So he had just written to his girlfriend about arrangements for their wedding. The future General George Marshall, who himself narrowly survived a shell in the war’s closing minutes, feared that some of his fellow officers longed for the last-gasp kudos of a “grandstand finish”, whatever the damage. On that ultimate morning, the Western Front witnessed 10,944 casualties, with 2,738 deaths. Astonishingly, that casualties total exceeds Allied losses on D-Day. Between 8 November, when the armistice terms had in essence been accepted, and the Eleventh Hour, 6,750 soldiers died. This parting spasm of slaughter is recalled far less often than the Christmas Truce, but looms like its dark double.

Apart from blood-lust, glory-hunting and robotic military routine, why did the war’s last hours exact such a heavy price? Europe’s governing and commanding classes shared a fatal taste for symmetry and symbolism. Hence the smug, even childish, satisfaction in a closure at 11am on 11/11. A misplaced sense of drama and ritual prolonged the agony. For the British, it gave rueful pleasure that the Great War should for their armies end in the recapture of Mons – where it had all begun, for them, in August 1914. Driven back from the city in the war’s earliest days, the 5th Royal Irish Lancers chose to stage a kind of told-you-so charge in its concluding minutes. So, at 10.58am near Saint-Denis on a hill above Mons, died Private George Ellison, the final British fatality. A minute later, the death of the German-descended Private Henry Gunther in a last-gasp assault would close the American – and entire Allied – account on the Western Front. It was claimed that, to avoid the taint of absurd ignominy, French troops killed on 11 November had their official record of death backdated to the 10th.

Even after this forenoon of meaningless carnage, the killing would not stop. A week later, on 18 November, two German ammunition trains moving home through Belgium exploded at Hamont station. More than 1,000 people died, and the blast virtually flattened the town. And, in this first global conflict, communications to the most distant fronts crept rather than raced. The German commander in East Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck, only surrendered on 23 November.

These last stands and late exits have a special potency. For many, they distil all the accumulated waste and loss of four preceding years. Wilfred Owen, with a lifetime of poetry ahead of him, had died on 4 November while crossing the Oise-Sambre canal, a month after being awarded the Military Cross for “fine leadership” and “conspicuous gallantry”. But the dreaded War Office telegrams took longer than shells to reach their target. So, just as across Britain church bells began to ring and town bands strike up, the Owens of Monkmoor Road in Shrewsbury received bad news, in Army Form B.213, on Armistice Day itself.

In Scarborough that July, prior to his return to the Front, Owen had written his “Parable of the Old Man and the Young”. Revising the Bible story for an age devoid of pity, Owen has Abraham sacrifice Isaac rather than save him. Deaf to the angel’s plea, the patriarch “slew his son, And half the seed of Europe, one by one”. The old men refused to let that slaughter end until the final seconds.

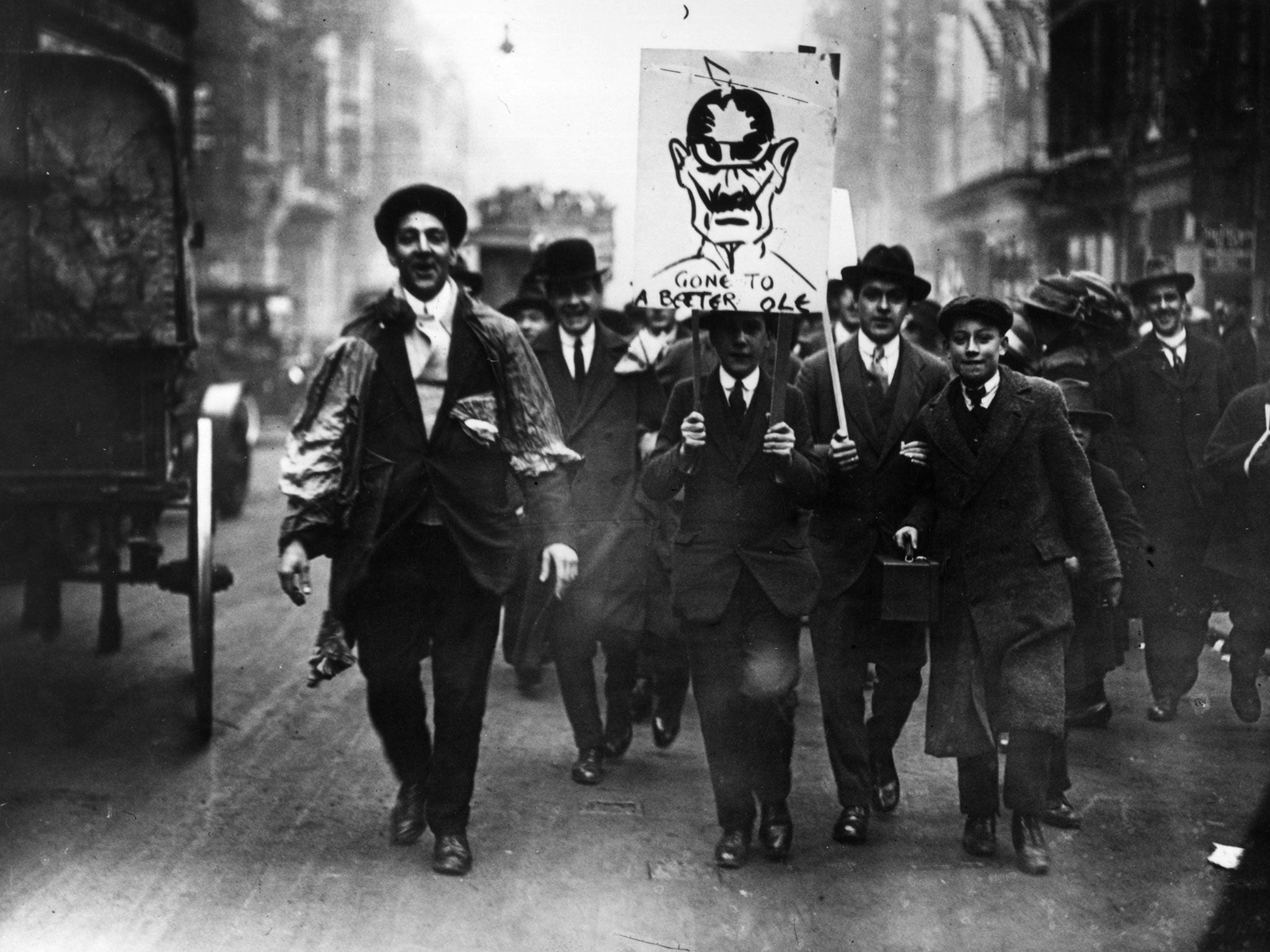

Like the close of the armed conflict, the rejoicing on the Home Front at the armistice had a ceremonial, even theatrical, quality. Some historians conjure up a scene of orgiastic mayhem. Most famously, AJP Taylor wrote that “omnibuses were seized, people caroused in strange garments, and total strangers copulated in the doorways and on the pavements”. But newspaper descriptions evoke more ritualistic, even solemn, scenes of joy. “Outside St Paul’s,” reported the Daily Mirror, “a shouting concourse included kneeling figures at prayer. Processions of soldiers and munition girls arm in arm were everywhere. American soldiers in jubilation invaded Downing Street. Conversation in the Strand was impossible owing to the din of cheers, whistles, hooters and fireworks.” The Manchester Guardian noted a formal quality to the relief. “The crowd gathered momentum in a most extraordinary way. In five minutes,” its correspondent observed on Fleet Street, “there was not an office window without a glaring new flag, till the street looked as if prepared for a medieval pageant.” If so, it could only have been the Dance of Death.

For her part, Vera Brittain – the battlefield nurse who would in Testament of Youth write a classic memoir of loss, mourning and regret – wandered through London that day in a stupor of “cold dismay”. The aftermath had already begun, and “in that brightly lit, alien world I should have no part. All those with whom I had really been intimate had gone”, her brother and fiancé above all.

That note of weary belatedness, of numb grief tempered by keen memory, begins to sound as soon as the guns fall silent. Ghosts crowd in to fill the vacant space, as in Virginia Woolf’s novel Jacob’s Room: “‘He left everything just as it was,’ Bonamy marvelled. ‘Nothing arranged. All his letters strewn about for any one to read. What did he expect? Did he think he would come back?’”

Apart from the 10 million or so dead who would never unlock their old rooms, 21 million suffered visible injuries. Uncounted millions more endured the anguish of post-traumatic stress, or “shell-shock”. Woolf wrote a pioneering case-history with her pitiable Septimus Warren Smith, in Mrs Dalloway, a stunned veteran who “could not feel” yet falls prey to “sudden thunder-claps of fear” at night and longs for the peace that only suicide might bring.

“Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically.” So begins one of the great English books about the First World War and its consequences – although no one recognises it as such. “The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes… We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.” DH Lawrence’s prescriptions for the aftermath, as expressed in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, would cause shock and controversy until half a century after the armistice – proof of business left unfinished and ghosts not laid to rest.

In their different ways, figures such as Brittain (who would overcome her despair), Woolf and Lawrence sought to imagine a better future. Yet Europe’s postwar tragic age would reveal that, for many survivors, only a better past could slake their grief. Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence would leap out from philosophy and into history. Hence the cruellest act of political symbolism on record – one that outdid every stagey flourish of 1914-18.

On 22 June 1940, former Gefreiter Hitler of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry ordered that France should surrender in the same railway carriage at Compiègne in which Germany had signed the armistice on 11 November 1918. The Fuhrer sat in Marshal Foch’s chair. Like Foch, in a deliberate act of mirroring, he brusquely got up and left after the preliminaries. In Europe’s long nightmare of a 20th century, the Eleventh Hour had merely marked a pause, not called a halt.

We hope to be able to publish “A History of the Great War in 100 Moments” as a complete collection, initially in e-book form, in early August. If you would like to be notified when the e-books are released – or, later, when a print book is published – please send an email to: WW1@independent.co.uk.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments