A History of the First World War in 100 moments: The first execution at the Tower of London for 167 years

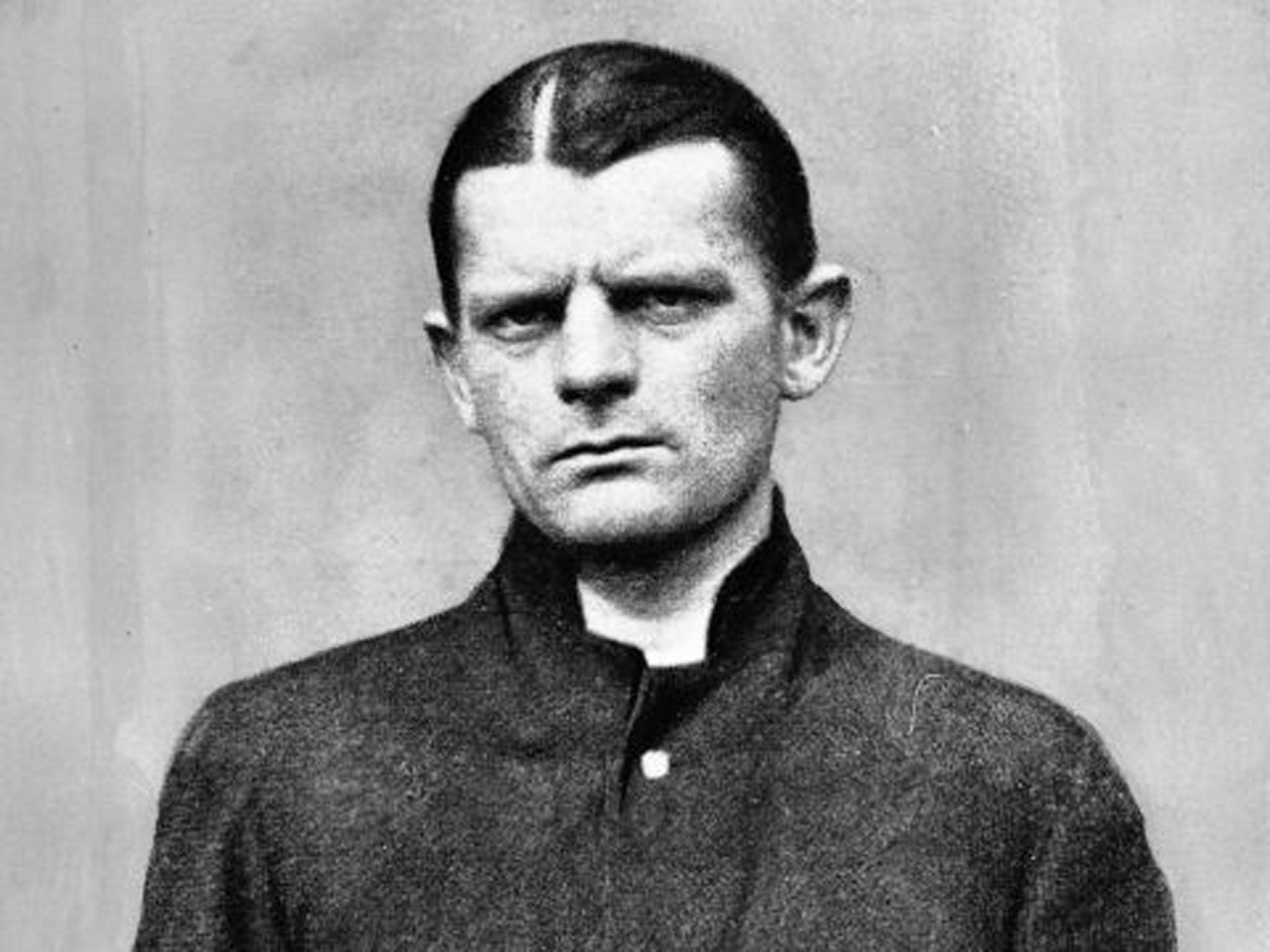

No.12 London, 6 November 1914: Carl Hans Lody was an inept agent. But he impressed his British captors with his dignified bearing as he faced a firing squad of Guardsmen, writes Cahal Milmo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 5 November 1914, Carl Hans Lody wrote a brief letter to the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards offering “sincere thanks and appreciation” for the care and “good fellowship” shown to him by his men.

At 7am the next day, the British Army delivered its response. On a foggy morning, Lody, 37, was led from cell 29 in the Tower of London, placed on a seat at the end of a long wooden shed that served as a rifle range and executed by a firing squad, as a nervous chaplain, his hands shaking, read from a book of prayer.

With this volley, followed by a coup de grace administered from the pistol of the officer in charge, Senior Lieutenant Lody of the Imperial German Naval Reserve became the first person to be executed in the Tower for 167 years. He was also the first of 11 German spies shot dead there during the First World War.

The delivery of the ultimate sanction to an enemy agent on home territory while the carnage of the Western Front was only beginning in earnest fuelled the febrile atmosphere gripping Britain in the early stages of the war.

Novels such as The Invasion of 1910 by spy pulp fiction writer William Le Queux, a fictional account of the German annexation of Britain serialised by the Daily Mail, had stoked fears that Britain would be overrun with legions of crack Teutonic operatives on the outbreak of war.

The reality, as the bold but inept efforts of Lody proved, was less threatening.

A pre-war visit to London in 1911 by Kaiser Wilhelm II had provided a boon to a nascent MI5 when the head of German naval intelligence, who was part of the delegation, was followed to a hairdressing salon near Pentonville prison. The address turned out to belong to the man charged with running Germany’s entire UK espionage ring, and its members were rounded up earlier in 1914, forcing Berlin to dispatch new and largely untrained agents such as Lody to Britain with the outbreak of war.

Born into a military family but thwarted by illness in his own ambitions to become a naval captain, Lody arrived in Edinburgh in August 1914 via Norway with instructions to monitor the Firth of Forth, a crucial anchorage for dozens of Royal Navy ships.

Using a rudimentary code, he sent back letters to his contact in Stockholm, offering information gleaned from rides on his hired bicycle about the configuration of British forces.

One of his messages, indicating that four ships were in dock for repairs, may have played a role in the arrival off Scotland in September 1914 of a U-boat which sank HMS Pathfinder – the first ship destroyed by a submarine-launched torpedo.

But unbeknown to Lody, who spoke perfect English with an American accent after living in Nebraska before the war and was posing as a tourist named Charles Inglis, MI5 already knew that the address he was using in Stockholm was used by German intelligence. His letters were seized by the mail interception service, staffed by 4,000 people, which was set up by MI5 at the outbreak of war.

Lody, who operated from an Edinburgh guest house, became sloppy, often writing letters in German. Some of his more fanciful missives, including one that reported the landing of “large numbers of Russian troops” in Scotland, were let through as misinformation.

He was eventually captured in October 1914 in Ireland, where he had fled after correctly becoming concerned that his cover was blown. The discovery of a tailor’s ticket bearing his real name and a Berlin address helped to confirm his true identity.

But while he may have been no master of deception, it was Lody’s conduct in the face of death that came to define him. Despite ministrations from MI5 that his case be heard in private so he could be potentially turned as a double agent, he was tried in public at the behest of a government keen to highlight its success in rooting out German moles.

With a formality bordering on courtliness, Lody admitted to spying, knowing the punishment for “war treason” was death, but declined to name his controller, saying: “That name I cannot say as I have given my word of honour.”

His gentlemanly declarations of patriotism during his trial, which was widely reported, won him admiration in Britain and Germany. Sir Vernon Kell, the founding head of MI5, told his wife he considered Lody a “really fine man” and “felt it deeply that so brave a man should have to pay the death penalty”.

Shortly after being told he was to be shot the following day, Lody wrote two letters – one of thanks to his captors and one to his family in Stuttgart in which he said: “A hero’s death on the battlefield is certainly finer, but such is not to be my lot, and I die here in the enemy’s country silent and unknown… I have had just judges and I shall die as an officer, not as a spy.”

As he was escorted to his death by eight Guardsmen, a witness noted the condemned man was the “calmest and most composed” member of the execution party. When the chaplain reading the words of the Burial Service as he led the way to the rifle range made a wrong turn, Lody stepped forward and politely caught the cleric by his arm, guiding him in the right direction.

Lody said to the military police officer in charge of the party: “I suppose you will not shake hands with a German spy?”

“No,” the officer replied, “but I will shake hands with a brave man.”

Tuesday: The great postal mobilisation

‘A History of the Great War in 100 Moments’ appears daily, in The Independent and in The Independent on Sunday. Earlier ‘moments’ in the series can be seen at independent.co.uk/greatwar

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments