A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Massacre at Wirballen

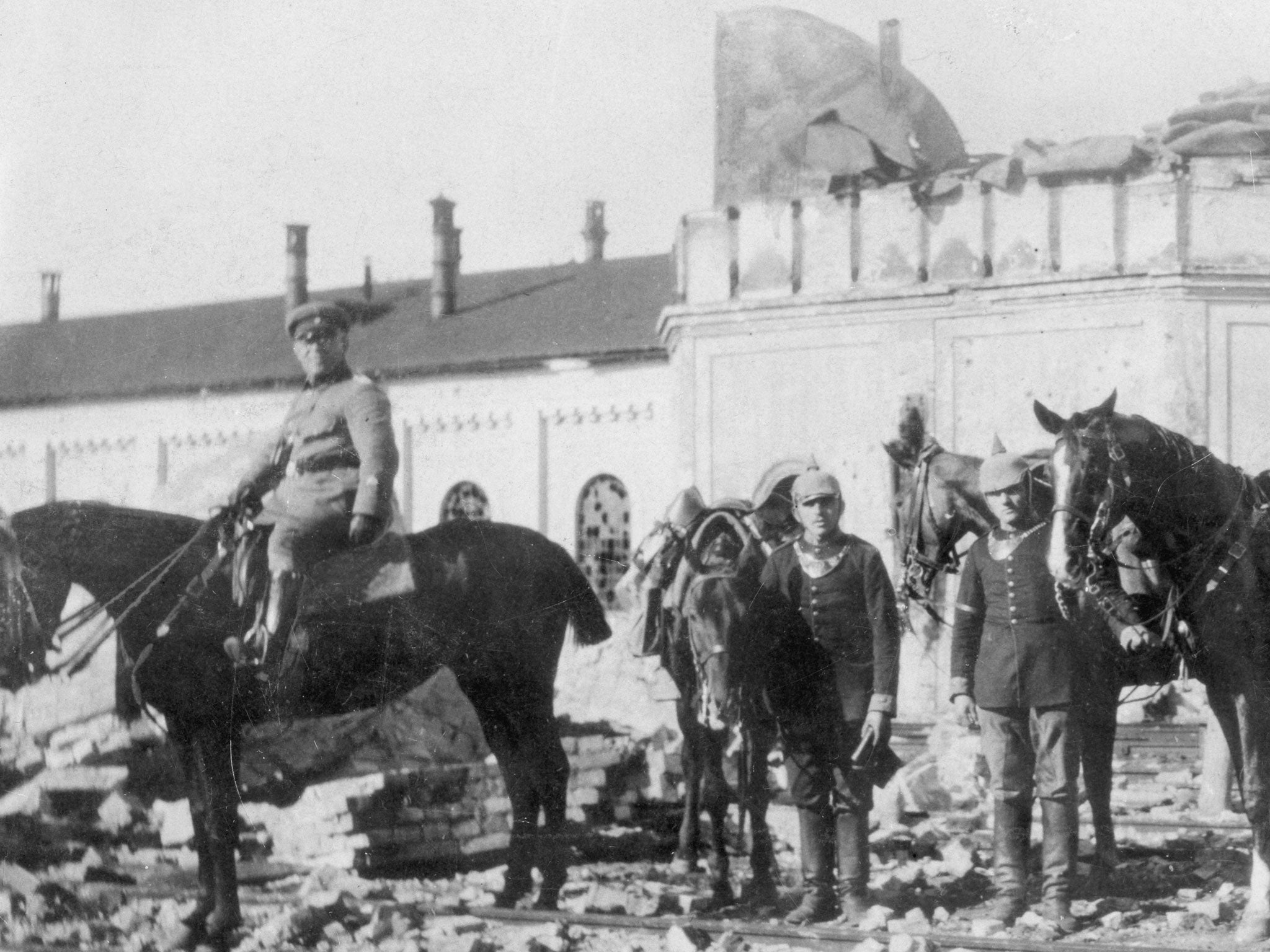

No. 11, The Eastern Front, 8 October 1914: Karl Henry von Wiegand, Berlin correspondent of United Press International, reports on the Germans’ lethal use of machine guns near Wirballen in Russian Poland

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At sundown tonight, after four days of constant fighting, the German army holds its strategic and strongly entrenched position east of Wirballen.

As I write this, I can catch the occasional high notes of a soldier chorus. For four days the singers have lain cramped in those muddy ditches, unable to move or stretch except under cover of darkness. And still they sing. They believe they are on the eve of a great victory.

I reached the battlefield of Wirballen shortly before daylight, armed with a pass issued by the general staff and accompanied by three officers assigned to “chaperone” me... We had travelled three days by auto and were within three miles of the right wing of the German position when we broke down and we went ahead on foot.

Today I saw a wave of Russian flesh and blood dash against a wall of German steel. The wall stood. The wave was shattered and hurled back.

Rivulets of blood trickled back slowly in its wake. Broken bloody bodies. We struck the firing line at a point near the extreme right of the German position shortly before daylight and breakfasted with the officers commanding a field battery…

While I was still marvelling at the number of details requiring attention in this highly specialised business of man killing, I was yanked out of my reverie by a weird, tooth-edging, spine-chilling, whistling screech overhead.

The fact that the shell was 500 to 1,000ft above me and probably another couple of thousand feet beyond, before my ear registered its flight, did not prevent my ducking my head.

A good many shells had passed over my head before I could lose an almost irresistible desire to hug the ground.

For half an hour the German battery paid no attention to the shells passing overhead and out of range. Finally a soldier with a telephone installed on an empty ammunition box began talking and copying notes, which the commander of the battery scanned hastily. A word of command and a lieutenant galloped along the line giving various ranges to the different battery commanders. The crews leaped to their positions, and the battery went into action.

The firing continued for perhaps 15 minutes, when there was a halt, more telephoning, a new set of ranges for some of the guns and a resumption of firing…

Now both the German and Russian shells were screeching and screaming overhead in a most uncomfortable if undangerous fashion. In the morning sunlight, from the summit of the hill, I got my first view of the fighting that will go down in history as the Battle of Wirballen.

The line stretched off to the left as far as the field glasses would carry, in a great, irregular semicircle, the irregularity being caused by the efforts of both armies to keep to high ground with their main lines.

As we watched, the entire fire of the Russian artillery seemed to be diverted on a village situated on a low plain about 2,000 yards to the northward of our position. The village – already deserted – was being literally flattened under a deluge of iron and steel.

The ruins were in flames. After half an hour the reason for shelling the deserted village became evident.

A general advance against the German centre was launched and the Russians were making certain that the village, directly in the line of advance, had not been occupied by the German machine guns during the night.

So far, though I had been witnessing a battle of obviously tremendous magnitude, I had not seen the enemy. From our position slightly in the rear of the German flank, it was comparatively easy to trace our own line through the glasses, but the general line of the Russians was hard to determine, being indicated only by occasional flashes of gunfire.

Yesterday, for the first time since the start of the battle on Sunday, the Russians attempted to carry the German centre position by a storm. All Sunday and Monday the opposing artillery had been hammering away at the opposing trenches. Twice under cover of their field artillery the Russian infantry advanced in force. Twice they were forced back to defensive positions. Now they were to try again. The preliminaries were well under way...

At a number of points along their line, the Russian infantry came tumbling out and, rushing forward, took up advanced positions awaiting the formation of the new and irregular battle line.

The German officers moved along in the open behind the trenches encouraging and steadying their men, preparing them for the shock. Finally came the Russian order to advance. At the word, hundreds of yards of the Russian fighting line leaped forward, deployed in open order and came on. One, two, three, and in some places four and five successive skirmish lines, separated by intervals of from 20 to 50 yards, swept forward…

From the outset of the advance, the German artillery, ignoring for the moment the Russian artillery action, began shelling the onrushing mass with wonderfully timed shrapnel, which burst low above the advancing lines and tore sickening gaps.

But the Russian line never stopped. On came the Slav swarm – into the range of the German trenches, with wild yells and never a waver. Russian battle flags... appeared in the front of the charging ranks.

The advance line thinned and the second line moved up. Nearer and nearer they swept toward the German positions.

And then came a new sight! A few seconds later came a new sound. First I saw a sudden, almost grotesque, melting of the advancing lines. It was different from anything that had taken place before.

The men literally went down like dominoes in a row. Those who kept their feet were hurled back as through by a terrible gust of wind. Almost in the second that I pondered, puzzled, the staccato rattle of machine guns reached us. My ear answered the query of my eye. For the first time the advancing lines hesitated, apparently bewildered. Mounted officers dashed along the line urging the men forward. Horses fell with the men. I saw a dozen riderless horses dashing madly through the lines...

The crucial period for the section of the charge on which I had riveted my attention probably lasted less than a minute. To my throbbing brain it seemed an hour.

Then, with the withering fire raking them, even as they faltered, the lines broke. Panic ensued. It was every man for himself. The entire Russian charge turned and went tearing back to cover...

I swept the entire line of the Russian advance with my glasses – as far as it was visible... The whole advance of the enemy was in retreat, making for its entrenched position.

After the assault had failed and the battle had resumed its normal trend, I swept the field with my glasses. The dead were everywhere. They were not piled up, but were strewn over acres. More horrible than the sight of the dead, though, were the other pictures brought up by the glasses. Squirming, tossing, writhing figures everywhere! The wounded!

All who could stumble or crawl were working their way back toward their own lines or back to the friendly cover of hills or wooded spots.

But there appeared to be hundreds to whom was denied even this hope, hundreds doomed to lie there in the open, with wounds unwashed and undressed, suffering from thirst and hunger until the merciful shadows of darkness made possible their rescue – by the Good Samaritans of the hospital corps, who are tonight gleaning that field of death for the third time since Sunday.

First filed as a UPI report, via The Hague and London, on 8 October 1914

Earlier ‘Moments’ are at independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments