A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: ‘I couldn’t bear the sight any longer. I lowered the periscope and dived’

U-boat commander Adolf von Spiegel describes his mixed emotions on sinking an Allied steamer

The steamer appeared to be close to us and looked colossal. I saw the captain walking on his bridge... I saw the crew cleaning the deck forward, and I saw, with surprise and a slight shudder, long rows of wooden partitions right along all the decks, from which gleamed the shining black and brown backs of horses.

“Oh, heavens, horses! What a pity, those lovely beasts! But it cannot be helped,” I went on thinking. “War is war, and every horse the fewer on the Western front is a reduction of England’s fighting power.”

I must acknowledge, however, that the thought of what must come was a most unpleasant one, and I will describe what happened as briefly as possible.

There were only a few more degrees to go before the steamer would be on the correct bearing. She would be there almost immediately; she was passing us at the proper distance, only a few hundred metres away.

“Stand by for firing a torpedo!” I called down to the control room.

That was a cautionary order to all hands on board.

Everyone held his breath.

Now the bows of the steamer cut across the zero line of my periscope – now the forecastle – the bridge – the foremast – funnel.

“FIRE!”

A slight tremor went through the boat – the torpedo had gone.

“Beware, when it is released!”

The death-bringing shot was a true one, and the torpedo ran towards the doomed ship at high speed. I could follow its course exactly by the light streak of bubbles which was left in its wake.

“20 seconds,” counted the helmsman, who, watch in hand, had to measure the exact interval of time between the departure of the torpedo and its arrival at its destination.

“23 seconds.”

Soon, soon this violent, terrifying thing would happen.

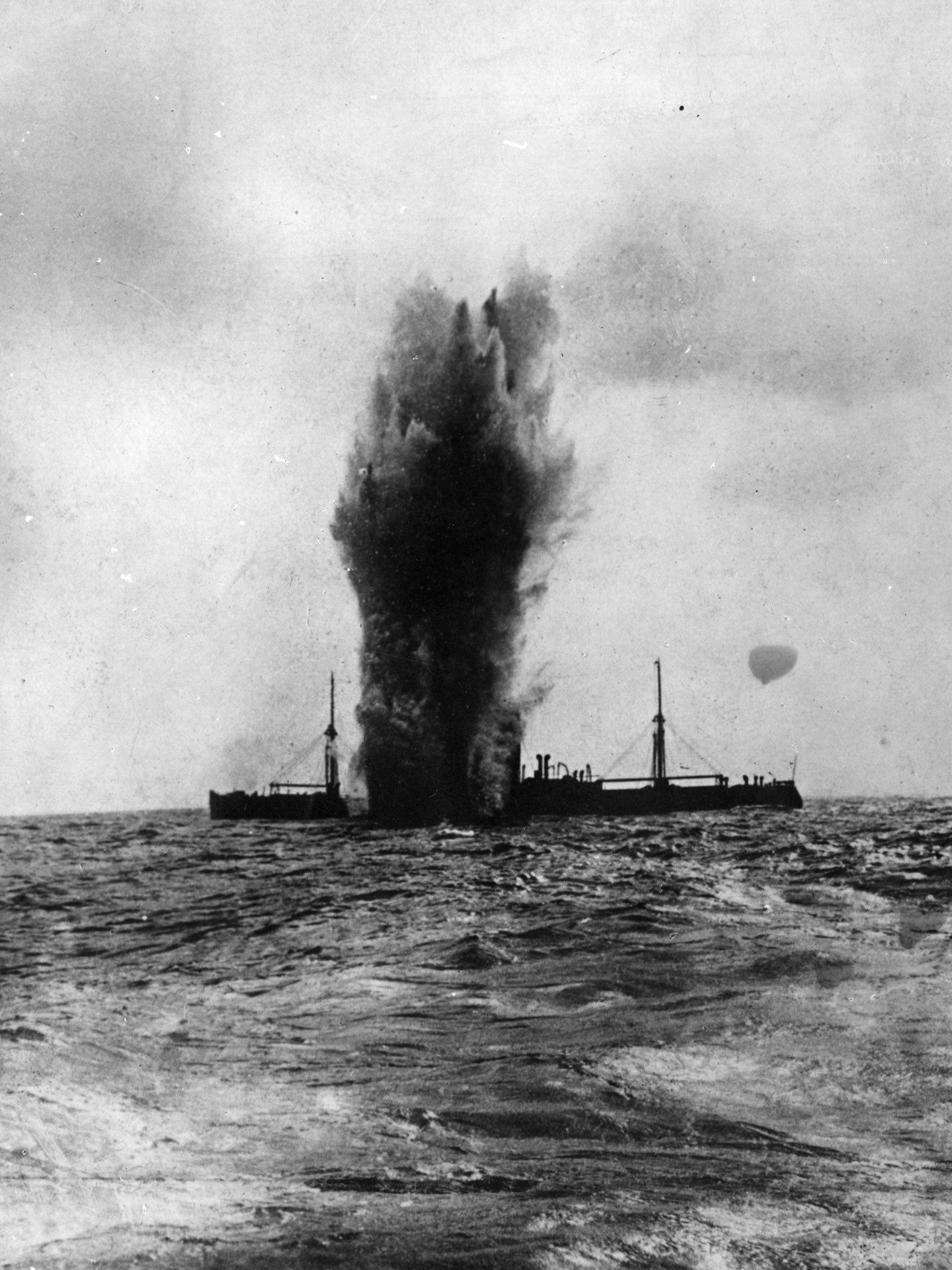

I saw that the bubble-track of the torpedo had been discovered on the bridge of the steamer, as frightened arms pointed towards the water and the captain put his hands in front of his eves and waited resignedly. Then a frightful explosion followed, and we were all thrown against one another by the concussion, and then, like Vulcan, huge and majestic, a column of water 200 metres high and 50 metres broad, terrible in its beauty and power, shot up to the heavens.

“Hit abaft the second funnel,” I shouted down to the control room.

Then they fairly let themselves go down below. There was a real wave of enthusiasm, arising from hearts freed from suspense, a wave which rushed through the whole boat and whose joyous echoes reached me in the conning tower.

And over there? War is a hard task master. A terrible drama was being enacted on board the ship, which was hard hit and in a sinking condition. She had a heavy and rapidly increasing list towards us.

All her decks lay visible to me. From all the hatchways a storming, despairing mass of men were fighting their way on deck, grimy stokers, officers, soldiers, grooms, cooks.

They all rushed, ran, screamed for boats, tore and thrust one another from the ladders leading down to them, fought for the lifebelts and jostled one another on the sloping deck. All amongst them, rearing, slipping horses are wedged.

The starboard boats could not be lowered on account of the list; everyone therefore ran across to the port boats, which, in the hurry and panic, had been lowered with great stupidity either half full or overcrowded. The men left behind were wringing their hands in despair and running to and fro along the decks; finally they threw themselves into the water so as to swim to the boats.

Then – a second explosion, followed by the escape of white, hissing steam from all hatchways and scuttles.

The white steam drove the horses mad. I saw a beautiful, long-tailed, dapple-grey horse take a mighty leap over the berthing rails and land into a fully laden boat.

At that point I could not bear the sight any longer, and I lowered the periscope and dived deep.

First published in “U-boat 202”, by Adolf KGE von Spiegel (1919).

Tomorrow: The fall of Kut

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar