A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: A big day at the enchanted chateau

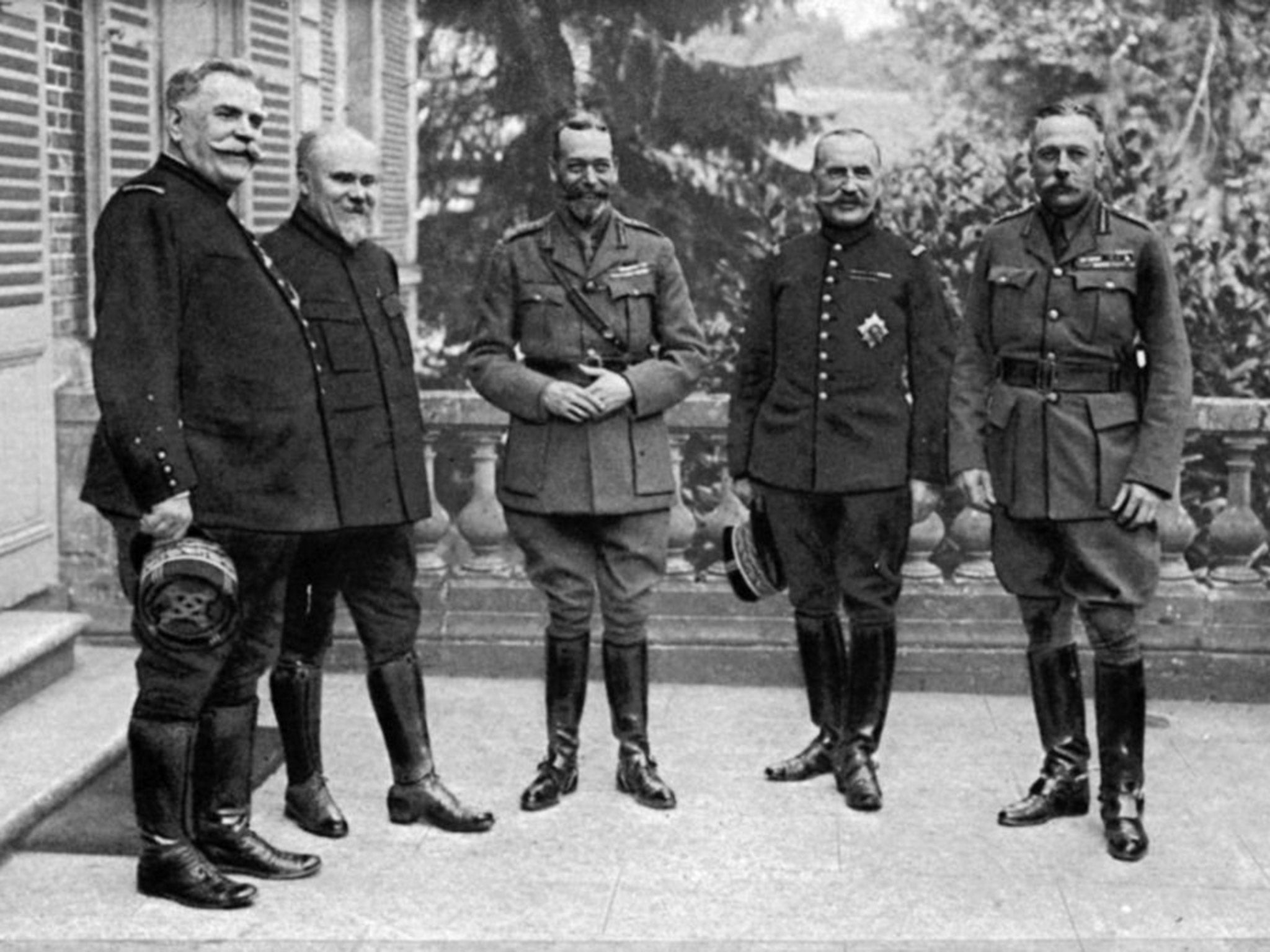

The military top brass plotted the war far from the horrors of the front. Jonathan Brown on the day George V came to stay

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The King’s arrival at the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the British Expeditionary Force in France was unlike most arrivals there.

For the ordinary soldier – or at least for the lucky few permitted to approach the fine old walled town of Montreuil where Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig had made his home and control centre – the road there was pockmarked with the ravages of war, to be negotiated in haste before returning all too soon to the dangers of the front line.

The King’s approach was more leisurely. Dressed in his field marshal’s uniform, he had disembarked from HMS Whirlwind at Calais on 5 August. The next day he inspected British and US pilots at Izel-les-Hameaux, handed out some Victoria Crosses at Blendecques, and eventually reached the cobbled streets of Montreuil on 7 August – the day before the start of the Battle of Amiens.

At GHQ, behind the swishing poplars at the nearby Chateau de Beaurepaire, he was greeted by Field-Marshal Haig and President Poincaré of France, and set foot in a world that could hardly have been more removed from the horrors of the war.

“One came to GHQ on journeys over the wild desert of the battlefields where men lived in ditches and pill boxes, muddy, miserable in all things but spirit, as to a place where the pageantry of war still maintained its old and dead tradition,” wrote Philip Gibbs in The Realities of War. For Gibbs, a correspondent hand-picked by the War Office to chronicle the conflict, the routines of life in GHQ – or the “City of Beautiful Nonsense”, as he would later scathingly name it – felt like a fairy-tale version of Camelot.

The home the military top brass had created for themselves was “picturesque, romantic and unreal”, he wrote. “It was as though men were playing at war here, while others 60 miles away were fighting and dying in mud and gas-waves and explosive barrages.”

Life in the town had taken on a surreal quality as the years of fighting passed and the bodies piled up in the blasted mud of the Western Front. Locals complained of rationing, curfews and rampant inflation.

Yet, according to Gibbs, writing in 1920: “War at Montreuil was quite a pleasant occupation for elderly generals who liked their little stroll after lunch and for young regular officers released from the painful necessity of dying for their country who were glad to get a game of tennis down below the walls after strenuous office work …”

For George V, a cousin of the Kaiser who had changed his family name to the English-sounding Windsor only the previous year, wartime visits to France were important propaganda occasions. But at GHQ, at least, he would have experienced a reassuringly familiar atmosphere of formality, deference and comfort.

The most senior officers were festooned with rows of medals earned in the Boer War. They all wore the smart blue and red armlet of GHQ staff. In contrast to the trenches, the chateau offered many distractions: football, roller-skating and swimming as well as fishing, painting and a cinema.

The officers had their own mess, in an old nursery school on Rue du Paon, a place that became notorious for the quality of its wine cellar, and for the members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps who dressed for each meal service in khaki stockings, short skirts and fancy aprons.

Daily life at GHQ revolved around Haig. Resplendent in polished cavalry boots and spurs, the Commander-in-Chief was in the habit of taking an afternoon ride, flanked by a personal escort of aides. Apart from his gallops through the countryside, Haig spent his days ensconced in meetings with his field cabinet and was rarely seen in the town except for his Sunday visit to the Scottish Churches Hut.

He had replaced Sir John French as commander-in-chief in December 1915, after a campaign of private letters to the King criticising French’s leadership and putting himself forward for the job.

He had moved GHQ from Saint Omer to Montreuil in the spring of 1916, a few months before his first big offensive, at the Somme. He felt that Montreuil was a better place to oversee the vast logistical industrial enterprise which the war had become. At its height some 2 million men served with the British Expeditionary Force. They needed feeding, clothing and arming. There were half a million horses too, all in need of fodder, 20,000 lorries and 250 train-loads of supplies arriving each day.

There were forests to cut down, hospitals to run, the dead to bury, allies to placate and political overmasters to obey – while all the time planning for the breakthrough needed to bring the war to a decisive conclusion.

Apologists for GHQ later argued that all of the above was carried out with only 300 officers stationed at Montreuil and 240 at the outlying directorates.

According to Australian-born journalist Sir Frank Fox, who served there: “At GHQ, in my time, in my branch, no officer who wished to stay was later than 9am at his desk; most of the eager men were at work before then. We left at 10.30pm if possible, more often later. On Saturday and Sunday exactly the same hours were kept … I have seen a staff officer faint at table from sheer pressure of work, and dozens of men, come fresh from regimental work, wilt away under the fierce pressure of work at GHQ,” he described.

Yet it was at least secure. GHQ suffered just two air raids during the war resulting in three deaths. Indeed, by the time of George V’s visit 20,000 refugees had fled to the area seeking safety. The King was to visit the town again just a few months later, not long after the Armistice, making a triumphant passage through the streets on his way to Paris. Field Marshal Haig returned to Britain the following April.

Tomorrow: Amiens - the battle to end all battles

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments