Freckleton air disaster 75 years on: Death and destruction on a school day unlike any other

In 1944, a US B-24 plane crashed into a school on the Lancashire coast, claiming 61 lives during an intense inferno. Here, Godfrey Holmes examines how such a tragedy occurred

On 23 August 1944 – as Paris was being liberated and Russia’s Red Army was pushing the German’s out of Romania – the Freckleton air disaster happened. Within the span of 15 minutes an entire village school was obliterated. The unlucky Minnesotan pilot: First Lieutenant John Bloemendal – experienced, athletic, handsome – had been instructed to conduct his “routine” test flight at 08.30. But he got distracted by other Warton Aerodrome duties, leading to a 10.30 reschedule.

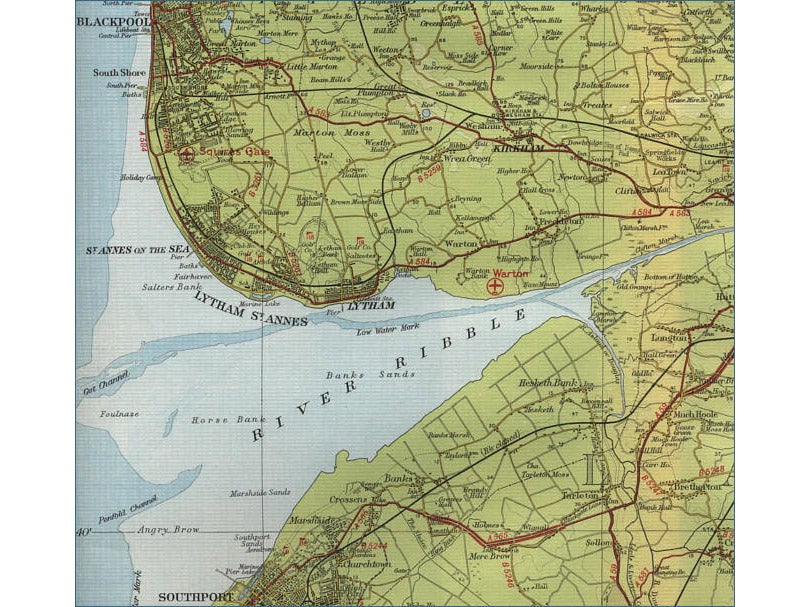

During the Second World War Freckleton, Fylde, was known as “Little America” due to an influx of 10,000 air force personnel: GIs bearing chocolate, citrus fruits and silk stockings. And why Warton Airfield? It was flat; coastal; fairly remote, yet not too far from Lancaster, Preston and Manchester for supplies; finely-positioned for crucial air reconnaissance and bombing sorties to north Africa, France and the Mediterranean.

And Warton was where aircraft could be serviced, refuelled, repaired: activities are still happening on site to this day – under the auspices of BAE Systems.

Bloemendal’s Consolidated B-24 Liberator aircraft, titled Classy Chassis II, was definitely not supposed to be flying alone on 23 August. Lieutenant Pete Manassero’s refurbished B-24 was to be alongside as the pair rose south over the Irish Sea. But to the southwest, leaden cloud quickly appeared: so startling, that two minutes after takeoff, Commander Isaac Ott ordered the control tower to call the exercise off.

In the air, Bloemendal was confronted by an impenetrable cloud ceiling at 400 feet: visibility less than 1,000 feet – no use whatever at high speed – so urged co-pilot Sgt Jimmie Parr, also Flight Engineer Sgt Gordon Kinney, to prepare for sudden landing. The plane’s undercarriage was duly lowered, then retracted, so the captain could fly round once more in hope of a safer descent. Meanwhile, Captain Manassero averted similar risk by heading due north, away from the enveloping storm of deafening thunder.

Because all three crew were incinerated in the ensuing tragedy, we rely on Freckleton’s Clitheroe Lane and Kirkham Road residents to discover what happened next. Undoubtedly, Bloemendal was far too low and slow to stay airborne. First he banked to the right, wingspan vertical instead of horizontal: in the process clipping a tree, losing the tip of his right wing. More hazards were hit in that awful storm: cables, hedge, then the corner of a building. Finally, whatever remained of the damaged wing ploughed a furrow in heavy earth before Bloemendal’s 25-ton flying machine partially demolished three houses, obliterated the Sad Sack Snack Bar, before its now detached fuselage crossed a sodden Lytham Road straight towards Freckleton Holy Trinity School.

In the school, two classes had come out of assembly ready to start their reading and writing. Then panic. Fierce flames were everywhere: tanks holding thousands of gallons of aviation fuel rupturing, then exploding. The crew had no realistic escape – nor did one of two teachers; nor 34 young schoolchildren.

That same week, four more children, one more teacher, one more American soldier – three more RAF airmen also – died in hospital of their burns. Only three pupils – disfigured and severely traumatised – are known to have survived: one telling BBC Radio Lancashire her harrowing story 50 years later.

Following the accident, service personnel, both British and American, sought refuge at the Sad Sack Snack Bar.

38

Number of children killed in the disaster

Before and between shifts, men like Corporal WW Cannell and RAF Sergeants Bill Bone and Ray Poole sipped tea, broke bread, conversed and relaxed with the Whittles – the owners of eatery. And although Bone and Poole head Freckleton’s survivor tally, their horrendous burns led to almost unimaginable suffering and irremediable scarring – to say nothing of post-traumatic stress – in succeeding months and years. Bone returned to the operating table no fewer than 49 times through to 1953; while Poole – who, like Bone, was dragged out of the inferno – needed complex surgery on 18 occasions.

A Freckleton Air Disaster Inquest was opened on 8 September, then, later, a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) panel of inquiry. Yet, beyond harrowing first-hand, and rescuer, testimony, no post-mortem was especially illuminating.

To start with, the B-24’s fuselage was totally destroyed in the conflagration. Therefore, no crewman could give accounts, nor were there more than three “miracle” children dragged out of two destroyed classrooms; nor were there too many Freckleton casual bystanders, due to the fierce nature of the thunderstorm.

Obviously, Warton Aerodrome and the control tower were helpful relaying their on-record pre-flight preparations and their frantic base-to-air instructions. Additionally, an unharmed Lieutenant Manassero who had flown in tandem with Bloemendel prior to changing direction could attest not only to rapidly deteriorating weather of 23 August, but also to his grateful embrace of the clearer visibility offered by the Vale of Eden.

It was concluded very unlikely the structure or engines of B-24 Classy Chassis failed on the day. Nor was there any lack of fuel: to the contrary, there was too much. Nor was Captain Bloemendal too inexperienced to undertake the different missions or expeditions to which he was assigned.

Therefore, despite encountering thick cloud months before, it was reasoned the captain and his co-pilot must have aborted landing at the first attempt due to combined lack of speed and altitude to get out of trouble.

The most useful recommendation to come out of various investigations into the Freckleton disaster urged preparedness for fickle weather in Britain. American air crews could have become a little complacent about local precipitation. Belief had grown up that the northwest experiences rather feeble storms: plenty of rain all year and a little distant thunder. Instead, that summer’s day proved that Lancashire – and indeed the whole of Britain – can suffer freak cyclones, torrents, maelstroms, lightning strikes – and daytime darkness.

Maybe both pilots really were a bit too dismissive of the gathering storm.

Even allowing for wartime, there were many constraints on reparation after Freckleton. One mother at least had far more to worry about than money – though a breadwinner in the family might greatly alleviate her finances. This was the mum who six days after losing her daughter to the inferno, received a telegram telling how her husband had been killed in combat in occupied France.

After Bing Crosby entertained shattered and demoralised USAAF personnel in Warton Hospital, their confederates had a quick whip-round intent on opening a memorial garden and children’s playground in Freckleton in honour of the isaster’s first Anniversary. On 23 August 1945, several American airmen constructed swings, climbing-frames and benches. Hence the inscription:

This playground is presented to the children of Freckleton

By their neighbours at Base Air Depot No2, USAAF

In recognition and remembrance of their common loss

In the disaster of August 23, 1944

Yet muddled planning and procrastination saw the promised Freckleton Memorial Hall having to wait until 1977 to be built: a case of too little, too late. Worse – and despite erection of a proper memorial within the churchyard of Holy Trinity Church – it took another 30 years from 1977 for a plaque to be placed at the exact spot B-24 lost its bearings.

Before leaving Freckleton – and, amazingly, very few families born and bred in its bounds have left their doomed village – it is apposite to consider the wider question of school safety. When parent figures leave their infants or juniors – even stroppy teenagers – at the school gate, they need to know all conditions are in place for their children to arrive home safe.

Similarly, the families of the Aberfan disaster of 1966 were not well-served by either the National Coal Board or government ministers. Their Pantglas Junior School was swiftly suffocated by coal slurry at a cost of five dead teachers and 109 dead children. And although, thankfully, no British school since 1966 has been completely destroyed, millions of children and their tutors have been subject to the inhalation of asbestos dust and vehicular particulates. Other children have been drowned or abandoned or subjected to avoidable road crashes on school journeys.

Admittedly, we are relatively unaccustomed for “high-school shootings” like those that so often plague the US – but quite possibly we still do not have preventive strategies in place. Not that any strategy could have prevented the Freckleton disaster on that cataclysmic day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments