Battle of the Somme: The moment that saved the life of 19-year-old Private George Howitt

With the centenary of the Battle of the Somme approaching, Keith Howitt set out to learn more about his father's time in the trenches. On Remembrance Sunday, our writer reveals what he was able to unearth on the battlefields of France

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am standing, gazing across a muddy field in northern France. It was here, on the night of 5 October 1916, that my father was wounded by a grenade, thrown at him from a German trench, probably a few yards behind me.

My dad, then a 19-year-old private soldier in the Gordon Highlanders, lay in this no-man's-land for many hours. His left leg was mangled by metal fragments, some of which had driven patches of his uniform kilt deep into his thigh. Eventually he managed to crawl back to his own trench, to safety and what would be a long life. He was a survivor of one of the bloodiest clashes in human history, the Battle of the Somme.

Next year's centenary of the battle will be marked by many commemorations. Monarchs, presidents and premiers will gather to pay tribute, and visitors from all over the world will come to retrace their forebears' footsteps across this emotionally charged landscape, and to remember the 1.4 million killed or wounded here.

This is the story of two journeys, a century apart, through the blood-soaked fields of the Somme. My father's took him from a little town in the north of Scotland to hell on earth and back. My journey has brought me to a new understanding of what that meant.

I only ever knew my father as an old man. George Howitt, born in 1897, Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year, was 59 (the age I am now) when I arrived. He was neither well educated nor well paid. He left school early, could barely write his name, and worked as a chauffeur and gardener. But he had been to war. And unlike any of my friends' dads, it was the First World War.

We spoke little about it. I knew he'd been in the Gordon Highlanders and been wounded – his thigh showed the scars of massive loss of flesh and muscle. And he sometimes showed me how to perform rifle and bayonet drill with a broomstick. I should have asked him to tell me everything about the war, but over the years I lost interest. I was growing up, pursuing girls, fun, and a career. And then, in 1983, he died, and it was too late.

But a couple of years ago, as the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War approached, I felt driven to find out everything I could about my father's time in the trenches. My compulsion was fuelled by a desire to understand what had shaped the man I loved. And I felt I had a duty, if only to my family, to record and honour the role – albeit small compared with others' – that my father played in shaping our world.

And so the quest began. I had some bits and pieces to get me started: his discharge certificates and two postcards the Army sent to his mother, informing her that her son had been wounded. This proved enough.

My first call was to the Gordon Highlanders' regimental museum in Aberdeen. It has an amazing band of volunteers who will, for a modest fee, search the regiment's records for you. Within days I received two A4 pages packed with more information about my dad's war than I had gathered in a lifetime.

It began for him on 13 February 1915, six months after the opening shots, when he enlisted as a volunteer in his home town of Keith, Banffshire. He was just 17, the fifth of seven children, and by all accounts a bit of a tearaway. He joined the local regiment, the 6th (Banff and Donside) Battalion Gordon Highlanders, part of the nation's Territorial Force of part-time soldiers. The war offered these young Scotsmen adventure, escape, a smart uniform – kilt, sporran, khaki jacket, bonnet, a good pair of leather hobnail boots – and a shilling (5p) a day pay.

It was probably towards the end of 1915 that he was sent to France: the first and only time in his life that my father went "abroad".

For me, the biggest prize in the museum report was a page from the 6th Battalion's War Diary, dated October 1916, which told me where and when my father was wounded. It was like being presented with a treasure map.

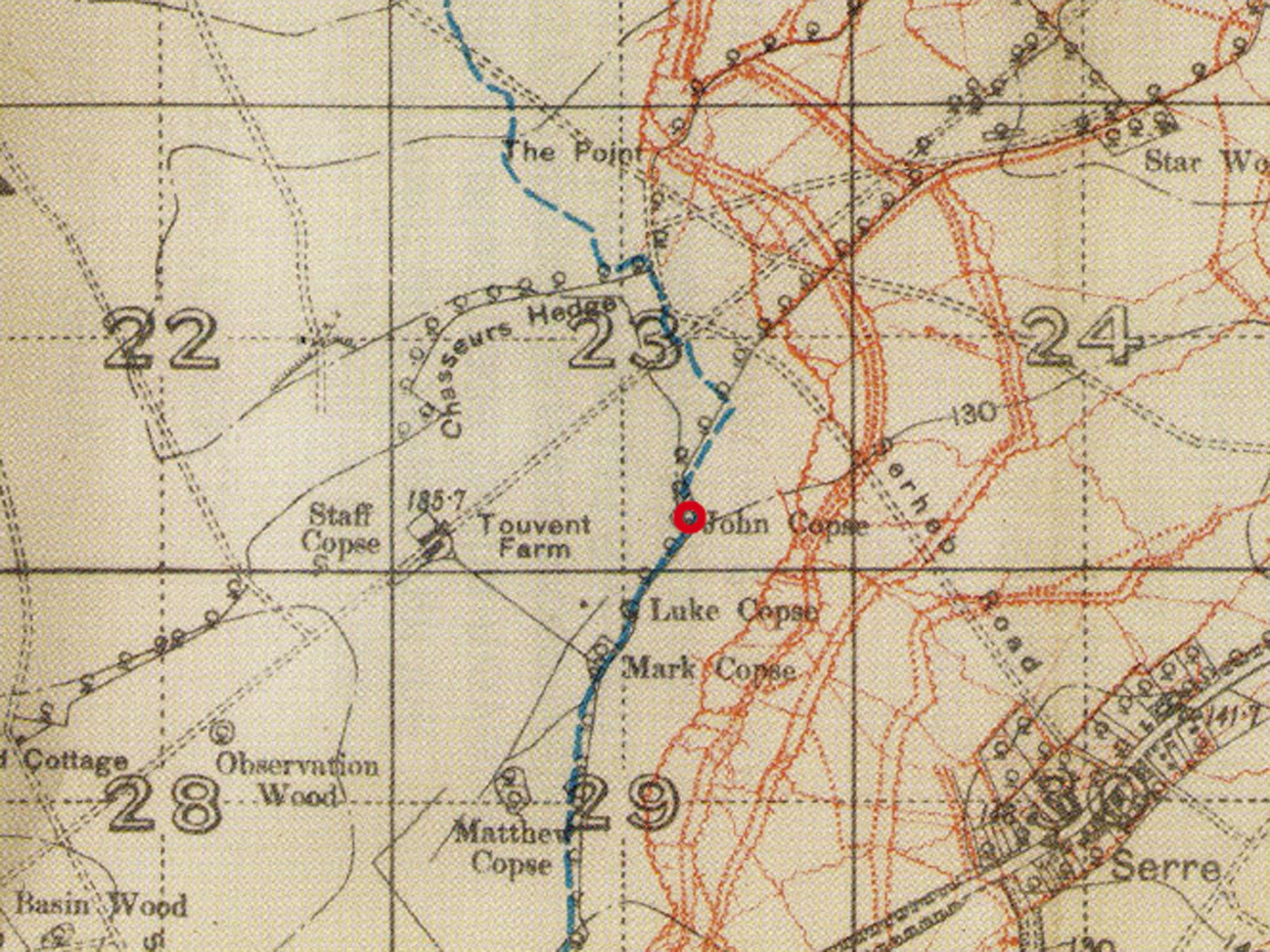

Over the following months I found out much more. From the National Archives at Kew I obtained the regiment's complete War Diaries, which even included the typed order sending my dad up to the front line that fateful October day. A few moments on the internet produced official trench maps from 1916, allowing me to pinpoint positions on today's landscape.

And my best and rarest find … a book published in 1922 for the families of the men who served alongside my father. I tracked down a copy of The Sixth Gordons in France and Flanders by Captain D Mackenzie MA MC to an antiquarian book dealer in Australia.

As I set off for France, Captain Mackenzie is my primary guide.

I cross the Channel on a car ferry – a world away from the packed troopship that carried my father – and, from Dieppe, I head for a Picardy village called Picquigny, where his regiment spent Christmas 1915 and then the New Year.

"The first faint glimmer of light was just creeping into the sky when the battalion reached the hill that leads down to Picquigny, and the men, all weariness forgotten, broke into song as they marched cheerfully to their billets," reports Captain Mackenzie.

A few weeks before my trip I had tracked down a local historian, André Sehet, and he is waiting outside the town hall with a small welcoming committee. They seem surprised I am not old and infirm, and I understand their confusion: I must be one of the youngest sons of a First World War veteran. Britain's last survivor of the trenches, Harry Patch, died in 2009, aged 111.

Picquigny was virtually unscathed by the war and looks much as it did in my father's time. We tour its sights, including the Somme river where, reports Mackenzie, some Gordons tried "clandestine fishing" – using hand grenades.

André is very pleased when I quote Mackenzie as saying the three weeks the Gordons spent here "are still regarded as one of the happiest times the battalion spent in France".

At midnight on New Year's Eve 1915, the Highlanders assembled in Picquigny's Grand Place. The pipe band played, they drank toasts in rum punch, and sang Scottish songs. For most of the young soldiers, this would be their first Christmas away from home. For many of them, it would also be their last.

We sit in a bar near the railway station. It was open for business here 100 years ago, says André. So I buy my guides a drink and raise a toast to the people of Picquigny for making my father and his comrades so welcome a century ago. There are smiles and handshakes all round.

On 6 January 1916, my father's regiment left for Abbeville, so I do the same. The Gordon Highlanders spent nearly five months here, guarding roads, railways, stores and prisoners. I seek out the Grand Place, where "the kilt, as usual, attracted much attention" and performances by the regiment's pipe band "were seen and heard with great enthusiasm by large crowds".

Now it's time to head north, to the village of Neuville-St-Vaast, from where my father first went into the frontline. He spent 18 days in trenches facing Vimy Ridge, the high escarpment held by the Germans since October 1914.

Life in the trenches was tedious. On alert every dawn and dusk; digging, fetching and carrying all night. Dreary meals of corned "bully" beef and rock-hard biscuits, washed down with tea made from water tainted by petrol and chemicals. Lice-ridden kilts. The daily delight of the rum ration. The daily risk of random death and mutilation by sniper or artillery shell.

Up on Vimy Ridge today, in a green moonscape of grass-covered shell holes, are some preserved trenches, their sandbags and duckboards cast in concrete to allow visitors a sterile taste of hell. It's better than nothing, but I feel it is all too antiseptic, too neat.

While my father was up here, 25 miles away to the south, on 1 July 1916, the British Army launched the bloody attack which was the first day of the Battle of the Somme. It was the darkest single day in Britain's military history, with 20,000 men killed and nearly 40,000 wounded. The preliminary artillery bombardment had failed to destroy the German defences and, as the young men from Sheffield and Accrington and Bradford walked towards the German lines, they were mown down. The meat-grinder battles would drag on until 18 November, with total casualties from both sides nearing 1.4 million.

As July turned to August, the 6th Gordons moved south to replace units destroyed in the carnage. They went into the line at a place called High Wood. I reach the same spot late on a sunny afternoon – but the glorious blue skies don't touch this dark and dismal place. It's privately owned, fenced off, and has been left virtually untouched since it joined the grim roll of the Somme's killing fields. The trees absorb all light and sound as I peer down murky paths from the road. There are ghosts here. "Attempts to carry the wood had failed, and we were hanging on desperately to the western edge," Captain Mackenzie says. "The tangled wreckage of trees … and the bloated bodies of the dead, swollen by the blistering summer sun to superhuman size, made each step a tense and nauseous ordeal." My father was here for five days.

Fighting in High Wood had started on 14 July, but by the time the Gordons arrived, the idea of any more frontal attacks had been abandoned. Instead they dug their way forward, inch by inch, under constant sniper fire. As each new trench was joined to its neighbour, they gained a bit more ground "at little cost". When the Gordons withdrew, they had lost 23 killed and 137 wounded. In the charnel house of the Somme, that is what counted as "little cost".

On 7 August, my father's battalion began the 65-mile trudge north to trenches near Armentières, which they manned for 19 days. A daring attack on a German strongpoint across no-man's-land was carried out by 45 officers and men "with great gallantry". They entered the German line and tossed in hand grenades. I have no idea whether my father was one of the 45 chosen men. I like to think he was.

The day before the raid, 21 September 1916, would have been his 19th birthday. The records suggest he was in camp in a place called Bailleul, so that is my next stop. I buy a pastis at a little bar on the square and raise a glass to dad.

It's time to head south again, as the never-ending rotation of units sends the 6th Gordons back to the Somme battlefront. The story of Private Howitt's war is nearing its savage climax. It is 4 October 1916 and the final orders are issued …

"The battalion will relieve the 13th Battalion Essex Regiment in the right sub-sector of trenches SE of Hebuterne today. Route of all units will be via St Leger Les Authie and Sailly Au Bois. Dinners will be served on arrival at Sailly Au Bois. Dress will be full marching order with packs. Kilt aprons [a khaki covering for the green and black Gordon tartan] and steel helmets will be worn."

I travel to Serre Road No2 military cemetery. It is the biggest in the area, containing 7,127 British and Commonwealth graves, of which 4,944 are unidentified. I have arranged to meet The Independent's Paris correspondent John Lichfield here. He knows the Somme battlefields well and will walk with me to the spot where my father was wounded. He takes me up the road and along a track to the trees known as John Copse and we stop to examine the 1916 trench map. "This is most likely it," says John. I look out at the ploughed land. Bare and brown and cold.

My father was right here on the night of 5 October 1916. I cannot remember if he said he was on a raid, on patrol, in a listening post, or merely repairing barbed wire in front of the British trenches. But he was here in no-man's-land when splinters of metal from a German grenade ended his war – and probably saved his life.

In big battles, the medical services were often overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of casualties. My father was one of just two men wounded here that night, so the medical officer would have seen him as soon as he dragged himself back to the trench line. His wound was dressed and he was sent away from the front.

If he had not been wounded, he would have faced another two years of bloody fighting. His chances of survival would have been poor. On the war memorial in my dad's home town of Keith there are 258 First World War names – 137 of them Gordon Highlanders. The town lost around 13 per cent of its male population. In total, the Gordons lost 9,107 men. Of those, 1,041 were from my father's battalion.

So a German soldier gave my father a ticket home, first to a hospital at Le Tréport, near Dieppe, then to Graylingwell Hospital, a requisitioned asylum near Chichester in West Sussex.

He would return to France, but not to the front. When his wounds healed, he was transferred to the Labour Corps, where one of his tasks would have been recovering and burying the dead. What further horrors he must have seen. On 11 April 1919, my father was honourably discharged from the Army.

I return to the field near John Copse the next day. It's cold and quiet beneath a grey sky. The trenches are gone, but I feel completely overwhelmed by the enormity of what happened here and the significance of this place in my life.

This time I walk out alone into the ploughed farmland. This is the actual spot. This place has obsessed me for two years. I am not ashamed to say that I start to cry. I think of my father, just a boy, wounded and cursing and frightened, lying bleeding on the ground in front of me. I bend down and pick some small blue flowers growing in the flinty soil. I will press them for my sister.

My father has been dead a long time, but as I walk back to the car I feel closer to him than I have for years. He won no medals for bravery, earned no promotion, and saw active service for only a few short months. But I have never felt prouder to be his son.

Keith travelled from Newhaven to Dieppe with DFDS Seaways (dfdsseaways.co.uk). He stayed at Hostellerie de la Vielle Ferme, Criel sur Mer (vieille-ferme.net); Grand Place Hotel, 3 Grand Place, Arras (grandplacehotel.fr); and Hotel Prieure, 17 Rue Porion, Amiens (hotel-prieure-amiens.com). For more: rendezvousenfrance.com; pas-de-calais-tourisme.com; amiens-tourisme.com. The Gordon Highlanders Museum is at St Luke's, Viewfield Road, Aberdeen (gordonhighlanders.com). For Somme centenary events: somme-battlefields.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments