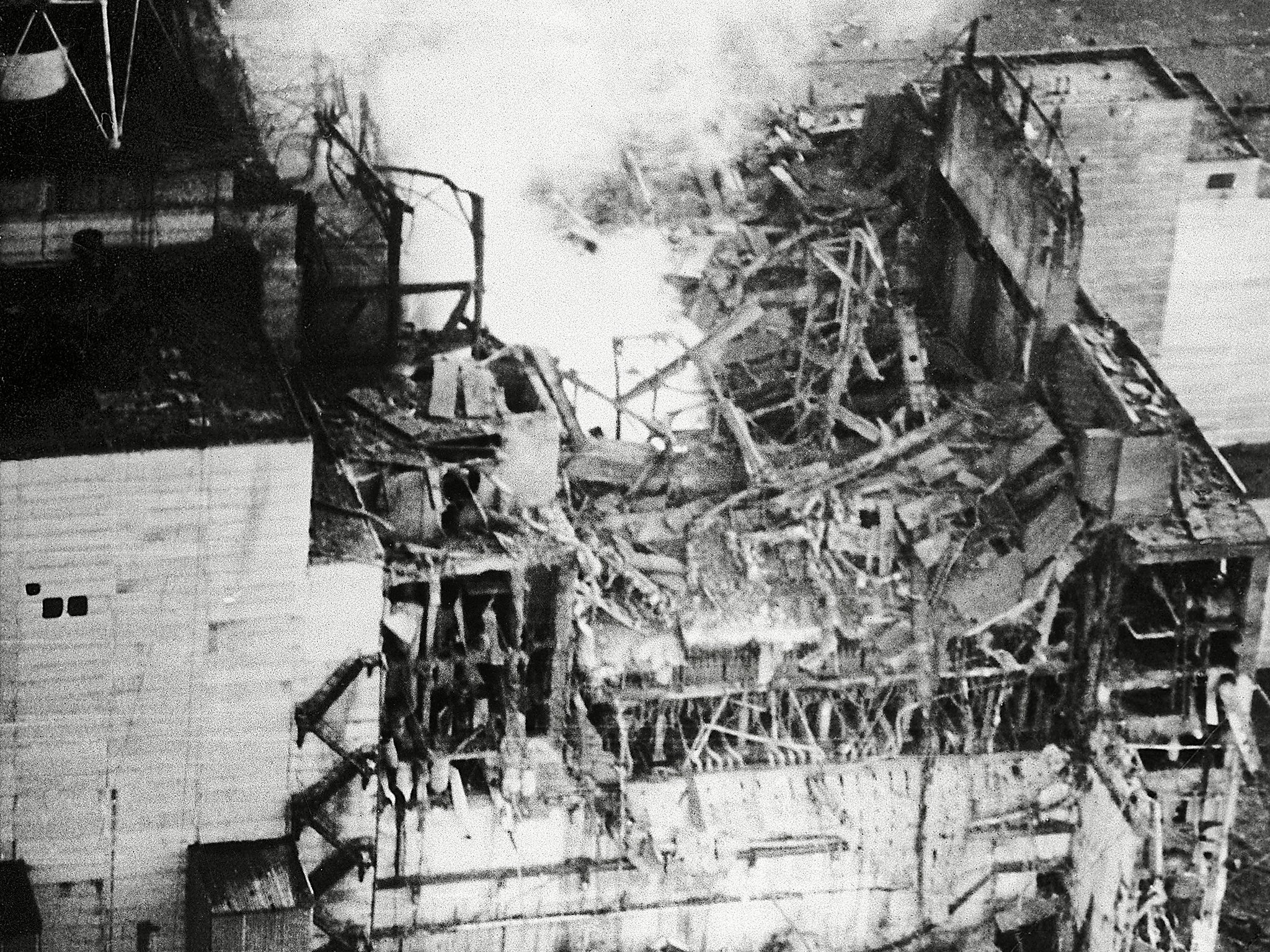

Radioactive milk and the lasting threat of Chernobyl

Fallout from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster still affects neighbouring Belarus whose press freedom, 30 years on, is also at risk of being contaminated

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thirty years ago Soviet authorities hushed the devastating accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in what is now Ukraine. Now a court in the country on its northern border, Belarus, has discredited controversial lab results detailing the potentially dangerous legacy of the catastrophe.

In April last year, journalist Yuras Karamanu visited areas of southern Belarus still contaminated from the Chernobyl accident. He came across cows grazing near an area where signs warned of radiation. A local farmer offered him a glass of freshly drawn milk. Instead of tasting the sample, Karmanau sent it to a lab in the capital, Minsk, to be tested for radiation – as it turns out, he did well to do so.

Initial tests at the state-run Centre of Hygiene and Epidemiology found “levels of a radioactive isotope 10 times higher than the nation’s food safety limits” – a fact he reported in his story for AP to mark the 30th anniversary of the disaster. Months later, however, the Belarusian journalist was to face another problem: a court case brought against him for writing the piece.

Three decades on from Chernobyl disaster, it seems the political fallout is yet to settle – now both Karamanu’s career and the future of investigative journalism itself in Belarus face meltdown.

The story started when malfunction at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in April 1986 caused a chemical explosion – 70 per cent of the radioactive dust created descended on Belarus. The fallout left swaths of the country uninhabitable and 20 per cent of agricultural land contaminated. The lives of more than two million of Belarusians – a fifth of the country – were affected.

Rates of thyroid cancers, particularly among children, skyrocketed. A 2002 report published by the UN described the Chernobyl accident as an environmental emergency adding “the outcomes of the Chernobyl catastrophe both for the population, as well as for the economy of Belarus, can hardly be measured.”

A 2005 commemoration of the Chernobyl disaster in central Minsk was broken up by Belarus’s Special Forces who detained journalists, activists, and opposition politicians. Amnesty International declared the hundreds of protesters, who were later handed fines or imprisoned, were “prisoners of conscience”.

Perhaps the most outspoken critic of government policy on Chernobyl’s legacy is Yury Bandazhevsky. In 1990 the 59-year-old scientist founded the first institute dedicated study the health impacts of Chernobyl – and then in 2001 he was sentenced to eight years in prison. His arrest on bribery charges was described as political both by Amnesty International and the National Academy of Sciences. Bandazhevsky was released in 2005 following a campaign supported by rock band The Cure. In his most recent interview from Ukraine, where he now lives in exile, Bandazhevsky said: “The problem of Chernobyl is not finished, it has only just begun.”

As recently as 2012, Belarusian human rights groups documented the detention and harassment of activists campaigning for a nuclear-free Belarus. Last year, six months after Yuras Karamanu’s milk story was published, the dairy company in the story went after him citing damages. In Belarus, where the legacy of the Chernobyl accident is contested by the government and the press is notoriously restricted (the country ranks 157th out of 180 states in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index), the verdict did not come as a surprise.

“The issue of Chernobyl has become taboo,” Karmanau told reporters before the first hearing in October. “Milk has become a ‘white oil’ for the state, exported to Russia. Milkavita exports 90 per cent of its products to Russia, to Moscow. And it is essential for the state to show that Belarusian milk is safe.

“All attempts to investigate the Chernobyl zone are faced with a morbid reaction from officials,” Karmanau added. “The state has closed the issue of Chernobyl.”

After a three-month legal battle, the judge ruled in favour of the company, Milkavita. The crucial moment of the proceedings came when Aksana Drabysheuskaya, chief engineer of the Centre of Hygiene and Epidemiology, recanted the findings her lab had relayed to Karmanu. She told the court that the readings Karmanau reported could not have been accurate because the sample was in a liquid state when it was tested and the milk had undergone the wrong testing procedure. Milkavita and the Belarusian Ministry of Agriculture agreed that the lab’s initial results could not be correct. The Economic Court in Minsk ordered the journalist to pay the legal fees of both the court and Milkavita – a total of £980 (2,340 Belarusian rubles).

Judge Tatyana Sapega ruled that Karmanau must retract the findings of his report in a written letter to his employer, Associated Press (AP). If the ruling is upheld after a pending appeal, authorities in Minsk may revoke the reporter’s accreditation. The Belarus Association of Journalists (BAJ) was among the first to criticise the ruling. “The result of this trial significantly narrows the boundaries of freedom of speech in the country,” the group said in a statement on the day of the court’s decision. “It calls into question the very possibility of significant investigative journalism in Belarus.”

Karmanau’s employer, which was barred from becoming a co-defendant on the case, also released a statement in support of the journalist and his work. “AP strongly disagrees with the court’s decision and unreservedly stands behind journalist Yuras Karmanau,” Ian Phillips, AP’s vice-president for international news, said in a statement. “Mr Karmanau’s reporting is a fair and accurate account of the lingering effects of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster on Belarus 30 years after the accident,” Philips added. “The court’s refusal to consider key evidence in support of Mr Karmanau raises serious concerns, and AP looks forward to vindication on appeal.”

The BAJ was quick to question why Karmanau was being held personally responsible for his investigation’s findings. Citing Belarusian media law, BAJ claimed that the journalist was not liable for the “dissemination of data not corresponding to reality, if that data is received from state bodies,” which includes the Centre of Hygiene and Epidemiology. However, the chief engineer, Aksana Drabysheuskaya, had argued that that the readings given to Karmanau were not “official state documents”, but were informal readouts. Moreover, Drabysheuskaya said the unofficial lab results were given, not to the AP, but to Karmanau, a private citizen.

For analysts familiar with case and Belarus’s repressive political climate, the result did not come as a surprise. “Independent Belarusian journalists know very well that the authorities do not condone investigative journalism, which focuses on public agencies or government-run projects,” said Igar Gubarevic a senior analyst at the Ostrogorski Centre based in Minsk. “Few people believe in the independence of the Belarusian judiciary system,” Gubarevic told The Independent. “A government-owned entity has no chance of losing a court case against a journalist, regardless of how strictly he or she adheres to journalistic standards.”

Belarusian political analyst Siarhei Bohdan told The Independent that “the government could respond by providing more information, inviting some authoritative experts, and explaining the situation. Yet so far we have more politicised speculations [of Chernobyl’s legacy] than studies and analyses that clarify the risks.”

Bohdan also questioned that the AP’s goal in testing milk, as opposed to a finished diary product, saying that the article may have been intended “to cause political scandal in Russia”.

The court’s ruling comes at a time when public opinion on nuclear power in Belarus is under the spotlight. Construction on Belarus’ first nuclear power station, which began in 2013, is now well under way. A series of fatal accidents on the construction site of BelNPP, which authorities initially tried to cover up, has sparked a debate on nuclear safety that has left Belarusians, some opposition politicians and government officials in neighbouring countries worried.

“Belarus avoids drawing public attention to the legacy of Chernobyl for two main reasons,” senior analyst Gubarevic explained. “The image of a contaminated country might hamper its efforts to promote exports and attract foreign investment and it may be at odds with the government’s newly adopted policy of pursuing nuclear energy by building the BelNPP. ”

Public opinion on the £9bn nuclear project is hanging in the balance. A poll conducted by the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies in June last year showed that a slight majority of respondents – 35 per cent – “disapprove” of the project. Anti-nuclear activists, including those detained by authorities, argue that the planning and construction of BelNPP have violated United Nation nuclear regulations and Aarhus and Espoo environmental conventions. These allegations are hotly denied by the government. Belarusian Nobel Prize-winning writer Svetlana Alexievich, whose collection of survivor testimonies, Chernobyl Prayer, painstakingly recounts the human impact of the nuclear disaster in Ukraine and Belarus, described President Alexander Lukashenko's decision to progress plans for the nuclear station as “a crime”.

“Belarus is a closed, authoritarian system, and the theme of Chernobyl is also a closed topic,” said Alexievich. “One person makes decisions in an authoritarian country, and he has decided to build a nuclear power plant,” she said, referring to Lukashenko. The BelNPP nuclear station in the unspoilt north of the country, which is seen as Lukashenko’s pet project, was originally devised as a solution to the country’s reliance on Russian energy. Minsk hoped to profit by selling surplus energy to neighbouring countries in the EU.

After 10 deaths and an accident involving a reactor casing at the BelNPP construction site, which is a mere 30 miles from Lithuania’s capital, foreign governments have turned against the accident-prone and Russian-constructed project. Lithuania’s president, Dalia Grybauskaite, who is staunch opponent of Russian influence in Europe, described Lukashenko’s BelNPP in August as an “existential” question for European security.

Tatyana Novikova, a thyroid cancer survivor and activist who has been detained by authorities for her opposition to BelNPP, says the Economic court’s ruling against Karmanau is in keeping with the government’s broader attitude towards the legacy of Chernobyl. “The Belarusian government is trying to represent the consequences of Chernobyl as a problem which is passing away,” she told The Independent.

''In other words, they try to convince citizens that the government has already done everything to protect them, and that the factor of time has eliminated radiation. The problem is that contamination will still be there and it is still a danger to people,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments