What Socrates, Aristotle and Leo Strauss can teach us about Donald Trump

It may sound like another partisan insult lobbed at the President-elect, but tyranny was not always a dirty word

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The election of Donald Trump has revived parallels between the United States and the precarious condition of European democracies in the 1920s and early 1930s. Democratic leaders, including President Barack Obama, have expressed hope for reconciliation.

Other opponents of Trump have been less restrained. Early on Wednesday morning, the filmmaker Michael Moore tweeted: “The next wave of fascism will come not with cattle cars and camps. It will come with a friendly face.” There was no doubt whom Moore had in mind.

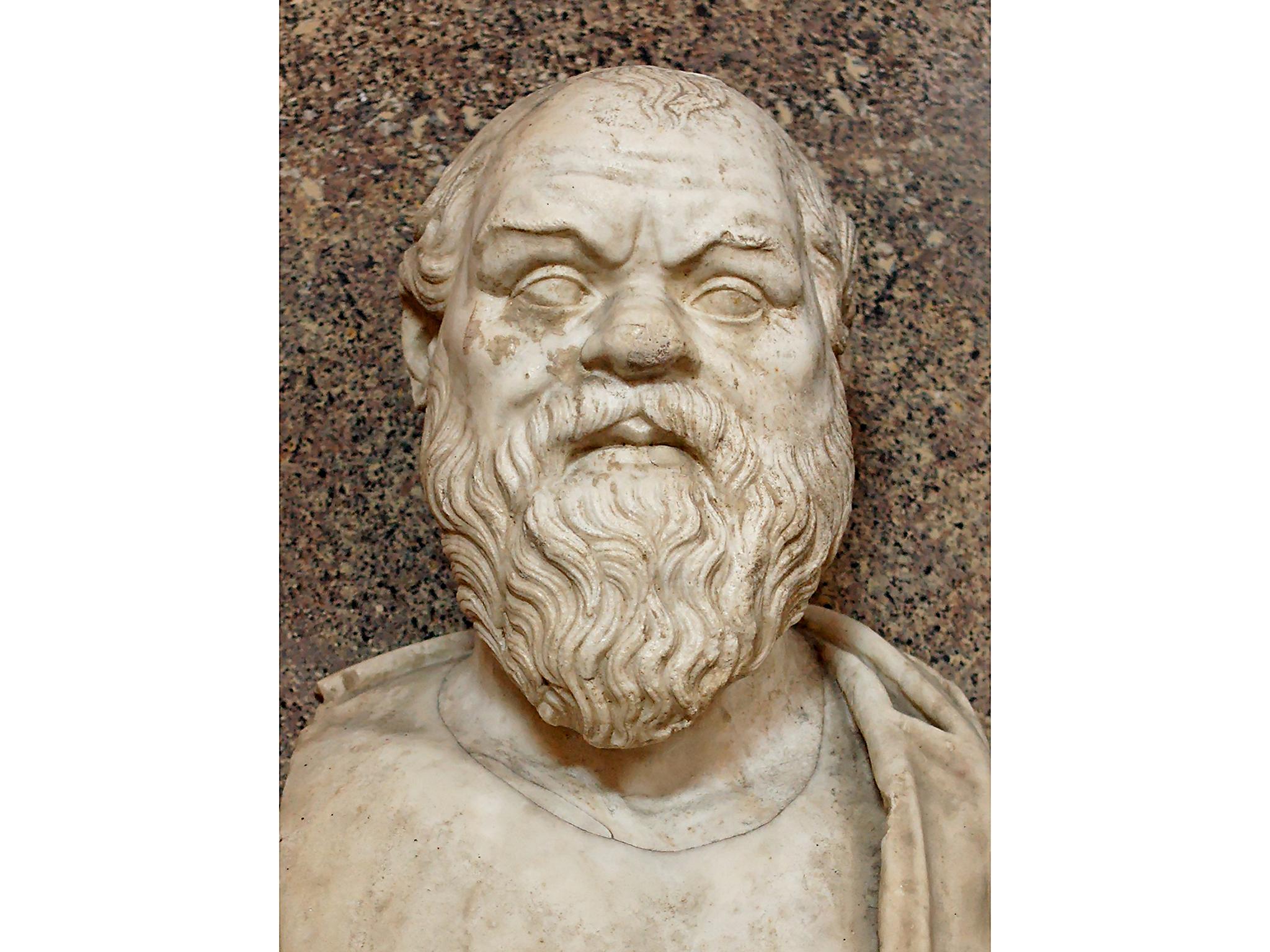

Some scholars are skeptical that Trump can be described as a fascist, arguing instead that he represents populism. But fascism and populism are not the only concepts that might help us understand Trump. The concept of “tyranny” – and how it was understood by the philosophers of ancient Greece – is particularly helpful.

Tyranny may sound like another partisan insult lobbed at Trump. But tyranny was not always a dirty word. Originally it referred to rulers who acquired power through extralegal means, often with the support of the rural poor. But it did not mean that the ruler was bad.

For example, consider the Greek ruler Pisistratus. The Greek writer Herodotus describes how Pisistratus took power in Athens in the 6th century BC: He faked an assassination attempt, convinced the people that he needed bodyguards and then used these bodyguards to seize power. Yet Herodotus reports that Pisistratus “administered the state constitutionally and organised the state's affairs properly and well”. Pisistratus was a tyrant, but not a bad ruler.

Plato offered a stronger critique of tyranny. He argued that tyranny was an evil form of government, but not primarily because tyrants took power in illegitimate ways. The problem was the tyrant’s distorted soul. Rather than loving what really matters – wisdom and justice – the tyrant seeks public approval and physical pleasure. But because these forms of gratification are ephemeral, the tyrant is never satisfied. He pursues more and more until he descends into madness.

The political theorist Mark Lilla points out that this way of thinking about politics has become unfamiliar to us. Modern political scientists tend to think about government in terms of institutional structures. For Plato, by contrast, tyranny is a psychological condition. (Indeed, the term psychology comes from psyche, the Greek word for soul.)

In The Republic, Socrates argues that tyrannical souls tend to arise in democracies. They are especially common among the sons of prominent men who do not enjoy as much prestige as they think they deserve. Tyrants gain power when they win the allegiance of the poor, often turning against their own elite class in the process. The parallels to 2016 are obvious.

Despite his criticism of tyrants as the unhappiest men and tyranny as the worst form of government, Plato seems to have wondered whether tyrannical rule could be harnessed for good purposes. He accepted an invitation to the Sicilian city of Syracuse to educate the tyrant Dionysius. But the experiment went poorly: According to the Roman historian Plutarch, Dionysius expelled Plato from Syracuse and arranged for him to be sold as a slave rather than be returned to Athens.

Other Greek philosophers considered whether tyrants could be good rulers despite the risks. In the work known as Hiero, or Tyrannicus (“the skillful tyrant”), Plato's contemporary Xenophon presents a dialogue between the wise poet Simonides and the tyrant Hiero. When Hiero complains that he is miserable and lonely, Simonides argues that he could win the esteem he craves by practicing justice and ruling for the common good. This would satisfy the tyrant's desires and the community's needs simultaneously.

Aristotle also offered suggestions for reforming tyranny. According to Aristotle, the tyrant “ought to show himself to his subjects in the light, not of a tyrant, but of a steward and king”. Aristotle contended that the best way for a tyrant to rule is simply not to govern like a tyrant. If a tyrant were to do so, Aristotle noted, “His power will be more last”. Aristotle realised that moral arguments wouldn't influence a tyrannical personality, so he appealed to the tyrant's overwhelming desire to be esteemed.

Greek reflections on tyranny did not figure much in modern social science until a debate in the mid-20th century between the political theorists Leo Strauss and Alexandre Kojève.

The dispute – carried on in the decade following the Second World War and collected in the volume On Tyranny – was not merely academic. Strauss and Kojève were both refugees from modern tyrannies: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, respectively.

Chastened by German academics' collaboration with Hitler, Strauss argued that intellectuals should keep their distance from politics. Kojève responded that an alliance between philosophers and tyrants was the best way to promote the rule of reason in politics. Despite his self-proclaimed affinity for Stalin, Kojève worked for the French government and played a significant role in establishing the European Union.

Given Strauss's warnings, it is ironic that some of Strauss's followers have been among the most significant intellectual supporters of Trump during the presidential campaign. These West Coast Straussians revere the Declaration of Independence, which protests against “the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States”. But they also emphasise the importance of decisive leadership in periods of crisis. In this perspective, a bit of tyranny may sometimes be necessary to save democracy from itself.

In the minds of many observers, American politics could see a re-emergence of tyranny. This only revives the old dilemma: Can personal rule be the means to achieving righteous ends, or is it inherently corrupt – and corrupting of those who participate in it?

Although they recognised tyranny's appeal, the Greeks remind us that rulers with distorted souls are dangerous. Even though they crave the support of the people, tyrants care only about themselves. In the so-called “Seventh Letter,” written after his return from Syracuse, Plato argues that “with regard to a State, whether it be under a single ruler or more than one, if, while the government is being carried on methodically and in a right course, it asks advice about any details of policy, it is the part of a wise man to advise such people”.

But, Plato argued, wise men and good citizens should refuse to collaborate with rulers who flout law and justice.

Sam Goldman is an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments