Utopia: Nine of the most miserable attempts to create idealised societies

There is a fine tradition of Utopias going terribly wrong when people tried to put their ideals into practice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Five hundred years ago, the lawyer and philosopher Thomas More wrote a book with an unhelpfully unwieldy title: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia. We can just call it Utopia – an original name, coined by More himself, for an original and hugely influential idea.

Derived from the Greek, that title means “no place”, but it hints at an alternative meaning: when the book was first published in 1516, it included a short poem claiming that the better world More described really was “Eutopie”, a “happy place”. It’s a paradox and a pun, playing on the British inability to distinguish between the pronunciation of the two terms, and it suggests that something’s not quite right. (The word “dystopia” seems to be a much later invention.) Is this paradise, whichever name you give it, unobtainable? That’s assuming the place really is meant to be a paradise in the first place.

Whatever it is, in More’s book Utopia is described by a traveller called Raphael Hythloday who bends the narrator’s ear with a survey of our own corrupt, far-from-happy side of the world before enthusiastically describing how much better things are in the island republic of Utopia on the far side of the world. There is no such thing as private property there, and no sectarian strife – but there is a welfare state (incorporating state-sanctioned euthanasia), as well as full employment, a programme of rehabilitative slavery for Utopian criminals, a democratic political system that works, a six-hour working day (many enjoy their work so much that they work longer, though), divorce courts, and a general disdain for gold and silver (which are used to make chamber-pots). Reason governs all – at least until Christianity comes along.

Hythloday’s description of Utopia has meant different things to different readers. In the 19th century, it could be drawn on as a prototype for Communism. A historian interested in the Tudor period could draw satirical lines between Utopia and the disorderly London that More knew all too well in his capacity as one of the city’s undersheriffs (he once had to face down a rioting mob). A good Roman Catholic familiar with him primarily as Saint Thomas More (he was canonized in 1935) could point out how divorce, married priests and euthanasia might not fit that easily with their beliefs.

All of these approaches ought to make us question what we think is going on in the book, just as More’s contemporaries and fellow humanists were invited to do. It started a centuries-spanning conversation – one sign of the book’s greatness – which this week takes the form of the London School of Ecomomics’ Space for Thought literary festival, devoted entirely to Utopias, the “power of dreams and the imagination and... the benefits of looking at the world in different ways”.

On the other hand, there is also a fine tradition of Utopias going terribly wrong when people tried to put their ideals into practice. It is true that some “intentional communities”, as those who study them like to call them, have flourished. But here are a few, imagined and historical, that show how acting on a dream can sometimes land you in a nightmare.

1. Thomas More’s troubled vision

You find yourself in a street in a small city – exactly which city is hard to say because all the streets in all the cities on this island are equal in size and virtually identical in appearance. All the buildings are the same height (three storeys each) and are constructed from the same materials. Perhaps you’re feeling thirsty? Well, tough: there are no pubs here in Amaurot.

Yes, this is Amaurot, the capital of city of the island-state of Utopia, where the very idea of a “public house” is redundant: every house is “public” because no house is “private”, and the double doors to each of those identical houses around you are not locked. You could walk into any one of them right now. The Utopians find this architectural uniformity saves them a lot of collective mental adjustment when they move house – which they do in a regular and orderly fashion every decade, by drawing lots.

As you would soon discover on your journey through Utopia – for which you would need a special licence, by the way – this is indeed a society founded on reason, organised rationally for the benefit of all. And the ultimate benefit of this rational hierarchy is pleasure – not just “any kind of pleasure”, please, but only “good and proper pleasure”, either for the body or the mind. You don’t need to be a raging libertarian to realise that living in the Utopia of all Utopias, is strictly for those who are rational, egalitarian and all but selfless.

2. Palmanova’s fortress for the few

From the air, the design of the Italian city of Palmanova is striking. It was originally a nine-pointed star citadel with ramparts and a moat, founded on 7 October 1593, as part of the Venetian Republic’s defences against the Ottoman Empire. Overseen by the veteran military architect Giulio Savorgnan with the most up-to-date defences built in, its construction was intended to express ideals of social harmony, at the same time as warding off any barbarians at the gates. The only snag was: nobody wanted to live there. The Venetians eventually resorted to pardoning criminals and offering them financial incentives to settle.

Since later regimes kept on adding to Palmanova’s defensive perimeter, an English visitor in the 18th century could say Palmanova was “beautifully laid out, but not quite finished”, while another, in the 19th century, after Napoleon’s few years in charge, could call it a “strong fortress, but a miserable little town”. So much for that idea. This immobile Renaissance Death Star barely ever saw any military action, perhaps because nobody could be bothered to attack it.

3. Henry Neville’s pornotopia

First published in 1668, the satirical narrative The Isle of Pines has been called a “pornotopia”. It tells of Dutch sailors who are blown off course in the southern hemisphere, spy land and, to their surprise, are welcomed on shore by naked islanders speaking English.

This community turns out to have been founded by an English bookkeeper called George Pines (swap around the surname’s vowels for the obvious joke) who was also blown off course and made landfall with only “my master’s daughter, the two maids, and the negro” female slave for company. He sleeps with the first three women quite openly; the fourth “seeing what we did, longed for her share”. By the time the Dutch arrive on the island, nature has taken its course: it is George’s grandson who rules the roost, and rebellion is stirring one branch of his extensive (yet closely related) family.

The Dutch help to restore order and then leave, but not before hearing that “whoredoms, incests and adultery” abound in this island paradise, and seeing that the civilised advantages with which the colony’s founders arrived have been forgotten. It’s difficult to say what Neville’s getting at, but some have read it as a kind of politically charged parable.

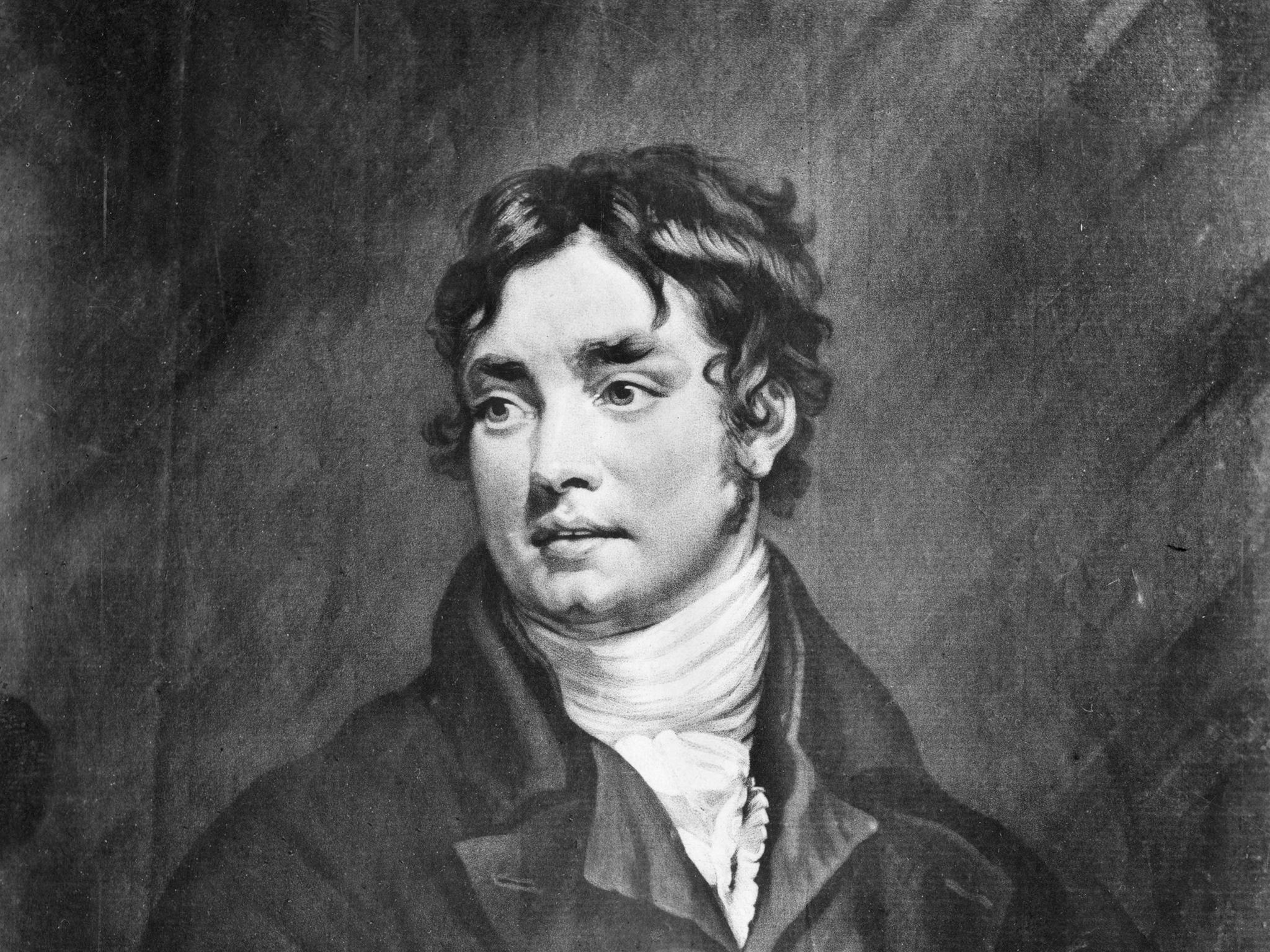

4. The poets’ Pantisocracy

Some Utopias fizzled out before they had even properly begun. The literary lives of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey could have been very different, or even non-existent, if only they’d had a little more money in their younger days. They met in Oxford in 1794, when Southey had already been discussing radical notions such as the abolition of private property with his friend George Burnett. Coleridge added his republican views to the mix and, between them, they cooked up a scheme for immigrating to North America to set up a “Pantisocratic” community founded on egalitarian principles. They identified the banks of the Susquehanna river as the place for a dozen families to start over, the following year.

It’s once the Pantisocrats started looking into practical matters such as, well, money that they realised they couldn’t even get to Pennsylvania, let alone build a new life there. Missing the point, Southey suggested they take servants with them to do the hard graft. He eventually settled for a farm in Wales and, 18 years later, was Poet Laureate to the monarchy Coleridge had condemned.

5. New Lanark, a near miss

In one sense, the village of New Lanark, south‑east of Glasgow, could hardly be called a failed Utopia, and shouldn’t be included in this list. Founded in 1786, it centred on the cotton mills that only closed in 1968; its inhabitants had been the beneficiaries of some laudable Utopian socialist principles, most famously those of the Welsh reformer Robert Owen. Many of the original residents had come from urban poorhouses. Owen built houses for them and opened the first school for infants in Britain in 1817. As somebody who saw his business turn a profit, but also saw his employees as more than just a workforce to be used and abused, Owen stands as a historical rebuke to more cynical capitalists of all ages.

Look at things from another angle, though: what did the Utopian conditions of New Lanark mean in the 19th century? A single room for a whole family; thousands of people lived like that. And although Owen’s successors respected his legacy, they failed to invest in machinery to keep up with competition, and the mills closed. New Lanark is now a World Heritage Site with a hotel, and deserves its high reputation – but it’s all too easy to take a rose-tinted view of its essentially industrial history, and a sobering thought that such conditions could be called a success. There’s much to admire about New Lanark – you can still visit it yourself, and even stay in the cotton mill converted into a hotel – but imagine living there for real.

6. Étienne Cabet and the Icarians

It was with Robert Owen’s example in mind, among other things, that a French lawyer called Étienne Cabet wrote his utopian fantasy, Voyage en Icarie. When it was published in 1840, its success led Cabet to think about putting his ideas into action on the other side of the Atlantic. He imagined 10,000 people pulling together in communist harmony – in Texas, which Owen himself had recommended.

Alas, things started going wrong straight away: for a start, there weren’t 10,000 Icarians; more like 69 pioneers made the initial journey (and Cabet himself wasn’t one of them). Then it turned out the Texan land agent had conned them into buying a completely impractical checker-board pattern of land. A course of further misfortunes led them to try again at Nauvoo in western Illinois. Here, things went well for a few years, only for Cabet to mess up by trying to impose his own personal authority on the scheme. He went off with 170 followers; the Nauvoo colony petered out and those survivors clinging to their principles moved to a second Icarian colony, in Iowa, which stuck it out until almost the end of the century.

7. Penedo, land of saunas

“The happy colonists are vegetarians and teetotallers...who help one another to build houses and to settle on their own little estates, sell the collected fruits and share the proceeds. They can live without too much toil, and thus have leisure for study, games and hobbies.” The Australian reporter who wrote these words in 1933 had seen an extraordinary thing: a group of Finns, led by a charismatic yet fraudulent man called Toivo Uuskallio, living in a former coffee plantation called Fazenda Penedo, in south-eastern Brazil. Divinely inspired, Uuskallio wanted to help “solve the terrible problem of world unemployment”. He wanted “a party of poor children from the East End of London” to come out and join him.

Fat chance. Penedo’s soil had been drained of nutrients during its time as a plantation. There was an infestation of leaf-cutter ants and a series of forest fires. Some followers went home; others were trapped there. They only got some shares in the land of their own after taking costly legal action against their leader.

On the bright side, it was here that Brazilians were introduced to the delights of the sauna. (The Finns’ assets turned out to be the culture they had brought with them.) Uuskallio himself died of starvation, aged 60. “He ate a lot of bananas”, a follower recalled, “but bananas alone can’t sustain a man”. Penedo survives him, and its principle business is now tourism.

8. JG Ballard’s hell on high

With Ben Wheatley’s film of the book out in March, and city skylines becoming increasingly dominated by shards, gherkins and all the other shapes, now seems like a good time to re-read High-Rise, JG Ballard’s savage novel of 1975, about everything going to the dogs (although it begins with one being eaten by its owner) in a luxury skyscraper.

Stratified by both economic and social class, isolated from the rest of the world (even though the City of London is only a couple of miles away), High-Rise describes how a populace of 2,000 tower dwellers descend into bloody chaos. Tribes from rival floors fight for control of the mod cons; they become incapable of meeting strangers except with suspicion or even aggression. And it is their being trapped in a vertical “concrete landscape” – an environment “built, not for man, but for man’s absence” – that seems to have this unravelling effect.

Ballard wrote the book following the rise of the Brutalist style of modern architecture exemplified by Ernö Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower in Kensington. Even as that block of flats opened in 1972, it was clear that tower blocks could cause drastic social problems. There was a price to pay for their soaring ambitions, and it was the residents who paid it. The Trellick is 31 storeys high. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the first sign of trouble in High-Rise, dog-eating aside, is a bottle of wine smashing on the protagonist’s balcony, after it’s seemingly “knocked over the rail by a boisterous guest” at a party on the top floor. The thirty-first...

9. Experiments in Utopian living

In 2005, the idea of living “off-grid” came to Dylan Evans. He duly found a good spot for establishing an independent community up in the Scottish Highlands, and issued an online invitation to others to join him. Things did not go according to plan: his book The Utopia Experiment begins with him waking up at 3am in a psychiatric hospital.

The idea of The Utopia Experiment was, in principle, simple and appealing; a group of voluntary Utopians would live, work and learn new skills together, over a strictly limited period of 18 months, playing out the likely scenario, in the wake of a global catastrophe, of having to fend for themselves. Utopianism isn’t just a whimsical side-project here but a potential survival strategy.

A hopeful start, however, gave way to all kinds of disappointment. The Utopia Experiment wryly tells of battling to keep the Scottish rain out of home-made yurts, arguments over religion – even somebody cutting a finger while chopping wood and having to be driven to hospital. Perhaps worst of all, Evans wonders why he has done any of this. Is it really about founding a better way of life – or is it merely a sign of depression?

In any case, as Evans admits, “To call something Utopian is...not entirely positive...The connotation of a perfect society is offset by that of a hopelessly impractical ideal”. Try telling that to the Icarians, Pantisocrats, inhabitants of the high-rise and the rest.

On 23 February, Michael Caines will be one of the speakers at ‘We Don’t Have to Live Like This: Experiments in Utopian Living’ , part of the LSE Space for Thought literary festival.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments