The Big Question: Is al-Qa'ida really cash-strapped, and is the threat it poses diminishing?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

The US Treasury says that al-Qa'ida is facing a financial crisis which is weakening it. It claims that the group is making appeals for funds and is saying that lack of money is hurting its training and recruitment.

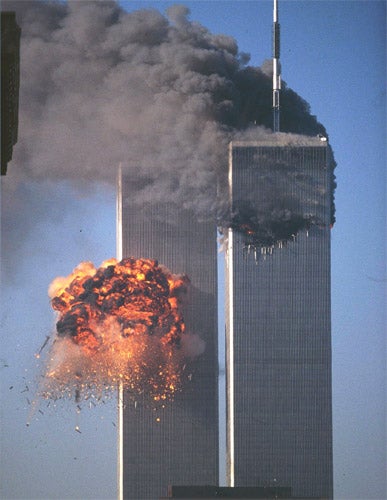

The Treasury contrasts al-Qa'ida's problems with the robust financial health of the Taliban. It has also been several years since there has been a spectacular attack on a western target by the group along the lines of 9/11 or the bombings of trains in Spain in March 2004 or the London transport system in July 2005. This may mean that the vastly expensive and pervasive security measures introduced since 9/11 have had some impact. It appears that al-Qa'ida is not the force it once claimed to be in Iraq or at an earlier stage in Afghanistan.

Is al-Qa'ida weaker than it used to be?

Yes, it is, but then it was never as strong as President Bush and Tony Blair declared after 9/11. In the minds of many in the West it was a coherent and tightly-knit organisation of fanatics, armed to the teeth and with hundreds of bases in the Afghan/Pakistan border region. In fact there were a dozen militants around Osama bin Laden who had concentrated another hundred or so men capable of providing the expertise for attacks on Western and other targets. Many of these had fought previously in Afghanistan against the Soviets as well as in Bosnia and possibly Chechnya.

It was never a big organisation and its strongest card was its ideology of militant resistance to the West and to allied Muslim governments at a time when both were becoming more and more unpopular across the Islamic world. At times al-Qa'ida was reduced to hiring local Afghan tribesmen at a daily rate to appear in its propaganda videos showing its militants in training.

Does it have less support now than at the time of 9/11?

It has been under constant pressure from western and local security forces. It has always been less of an organisation than a series of franchises in Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere in which local groups call themselves al-Qa'ida and owe it nominal allegiance. But these groups do not answer to a central leader and their success and failure depends very much on local conditions.

Does that mean the world is safer from attacks by al-Qa'ida?

Not really. Many conspiracies attributed to al-Qa'ida develop among a small group of locally based fundamentalists. It may not matter to them what al-Qa'ida does or the extent of its organisational strength or lack of it. Some money is required, but not much.

The degree of provocation felt by the 1.3 billion Muslims in the world also matters if al-Qa'ida is to win the support of a small minority. Anger was high after the occupation of Iraq; this lessened after the US said it would withdraw and Barack Obama was elected president. An escalation of the US war in Afghanistan may once again lead to more backing for al-Qa'ida-style attacks. But this would probably happen regardless of the fate of the al-Qa'ida organisation.

What happened to al-Qa'ida in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq?

In all three countries the sort of massive suicide bombing which used to be the trademark of al-Qa'ida is now used by other organisations. Even if it languishes, its Jihadi ideology has been disseminated among militants.

What are its weaknesses?

Al-Qa'ida and kindred organisations tend to overplay their hands. They have the advantage of a core of committed fighters. But their fundamentalist ideology is often parasitic on national and social discontents. Attempts to impose fundamentalist and sometime barbaric religious norms may lead to a reaction against the Jihadis. This happened in Chechnya in the second war against Russia starting in 1999. Religious militants, the Wahabi, were ferocious fighters but also alienated many Chechens.

In Iraq, al-Qa'ida, always rooted in the Sunni community, provoked bloody retaliation by the Shia majority. Insurgent Sunni leaders who had brought the group into Iraq switched sides and allied themselves with the Americans. The limited appeal of their fundamentalist brand of Islam was obvious. In Pakistan initial support for local Taliban in the Swat valley was likewise eroded by brutal enforcement of their beliefs.

So are British troops in Afghanistan there to defend the UK from al-Qa'ida attack, as Gordon Brown says?

No, we are there because the priority of British foreign policy is to stick close to the Americans. The Americans are still trying to work out why they are there, but President Obama is also citing the need to deny al-Qa'ida a base. Undermining this argument is the fact that al-Qa'ida and similar groups are primarily located in Pakistan these days and there they can tap into support from fundamentalist groups not just in the borderlands, but far to the east and south in Lahore and Karachi.

Has al-Qa'ida failed?

On the contrary, an aim of 9/11 and other attacks was to lure the US and its allies, essentially Britain, into an over-reaction and a direct occupation of Muslim counties. This would enable the Jihadis to mobilise support and fight the infidels directly. Television screens across the Islamic world would be filled with the sight of burning Humvees. The confrontation al-Qa'ida wanted to bring about has happened. 9/11 was essentially a trap into which President Bush and Tony Blair promptly jumped. The interrogation of would-be suicide bombers in Iraq shows that their prime motivation is not Islamic fervour but anger over the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Will al-Qa'ida rise again?

Possibly not, but its formula for political and religious action is likely to live on. The Taliban in Afghanistan now distance themselves from the group, but their actions increasingly mirror those of Osama bin Laden's followers.

Could it mutate into something different?

Some Islamic militants see Hizbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza as showing the way forward rather than al-Qa'ida. In both cases there is a militant core, but it is one that reaches out to a wider constituency. The unpopularity of existing governments across the Arab world – and most of the Muslim world – is even greater than it was a decade ago. The departure of President Bush meant that the demonic enemy whom it was so easy for al-Qa'ida to rally support against was no longer there. This was bad news for al-Qa'ida, but its leaders must be relieved to see the US committing itself to a wider war in Afghanistan.

So has al-Qa'ida had its day?

Yes...

* That the organisation is on the run is clear from the lack of any big attacks recently.

* Western security measures have worked, and the bombers can no longer get through.

* Its presence in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq is much weaker than a few years ago.

No...

* Suicide bombings are still easy to organise and could happen at any time.

* As the IRA showed when bombing the City of London, security can never be 100 per cent effective.

* The group is more of a franchise than an organisation and may re-emerge anywhere.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments