Special report: The new model armies - why are Western forces being deployed across Africa?

The new mantra of 'muscular soft power' is designed to fight insurgencies and prepare states to defend themselves while building up infrastructure and civic institutions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The road to Bamako lay wide open. It was only a matter of days, hours even, before fighters linked to al-Qa’ida, who had already taken over most of Mali, took the capital, a triumph for jihad. But the arrival of French forces halted the advance, and a fast and incisive counter-attack saw the rest of the country freed from the insurgents. Timbuktu, where they had begun to destroy historic manuscripts and mausoleums, was saved. While France’s Mali mission was a success, it does not provide a template for Western involvement in Africa. The mantra now is “muscular soft power”, the process of preparing states to defend themselves while building up infrastructure and civic institutions. It is hoped such steps will make large expeditionary operations a thing of the past.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have left the public weary of foreign adventures. Even a relatively risk-free enterprise like Nato’s bombing of Libya in 2011 now holds little appeal as the Arab Spring turns into winter and uncertainty abounds about who exactly are the “good guys”. Defence cuts in Europe and the US have reinforced the view that days of prolonged combat and nation-building are, for the time being, over.

The errors of Afghanistan were articulated during a visit to London last week by James F Dobbins, the US special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan. He believes the war was prolonged and lives were lost unnecessarily as a result of the failure to drive through reconstruction and development, and the rejection of Taliban leaders who wanted to communicate.

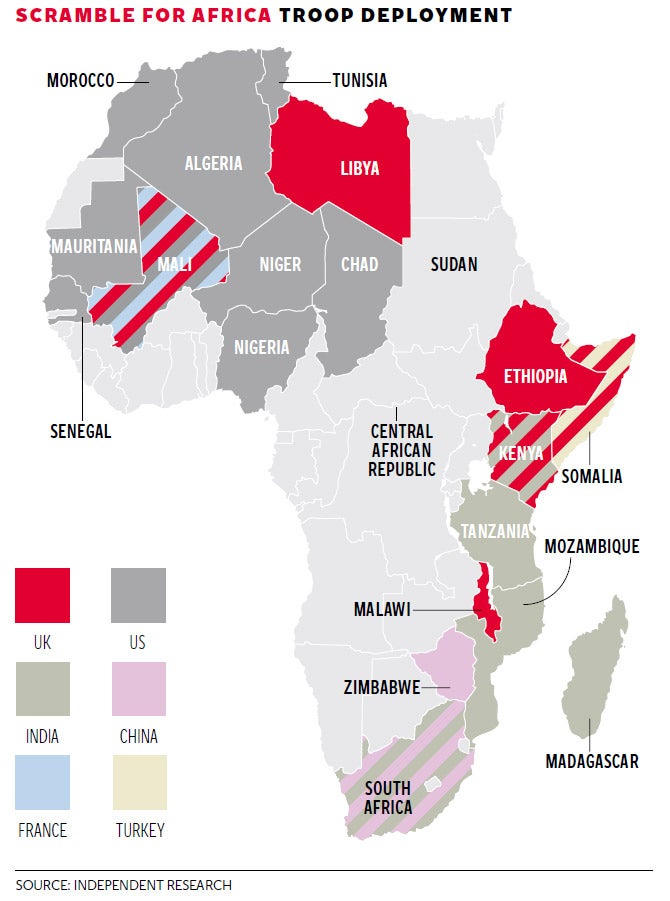

The Afghan experience can, say analysts, assist the soft power strategy. But Western intentions in Africa are not entirely altruistic, and there is competition for influence in a continent rich in minerals and commercial potential. China, desperate for resources and undertaking endless construction projects, is now flexing its military muscle. Chinese troops were seen recently patrolling with Zimbabwean soldiers in Mutare, while at the same time the freighter An Ye Jiang was docked in Durban packed with weapons for Robert Mugabe’s regime.

The ship was forced to head back east after the dockworkers union refused to unload it but South Africa has welcomed the offer of closer military ties with Beijing. Maj Gen Ntakaleni Sigudu of the South African Defence Ministry reminded his countrymen that training given by China to ANC cadres hastened the end of apartheid. Beijing has also offered counter-terrorism expertise to Nigeria and sent defence attachés to a number of states including Cameroon. India now has a series of defence agreements with Kenya, Mozambique and Madagascar, where it has established training programmes alongside those it runs in South Africa and Tanzania. Turkey, meanwhile, has announced it will be offering defence assistance to Somalia and some Arab states.

There is international consensus that failing states should not become havens for the next wave of terrorists keen to attack the West. The aim is to do so without committing troops, with the Central African Republic a potent example. As the UN warns of impending genocide, it has become the lethal playground for indigenous Seleka rebels along with fighters from al-Qa’ida in the Maghreb, Nigeria’s Boko Haram, Sudan’s Janjaweed, the Lord’s Resistance Army and Malian Islamists. France has kept around 400 troops in the capital, Bangui, to keep the airport road open. But, unlike in Mali, the government insists it will be African Union troops rather than Foreign Legionnaires who will be patrolling it. There may be a small-scale reinforcement from Paris, but Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius insisted there wouldn’t be intervention “in the classic sense of the word”.

“We are not going to send parachutists, but there needs to be a presence because the state has been completely unseated,” he said. EU partners would be expected to help, and senior French diplomats have been to London recently to drum up support for future training.

The last British campaign in Africa was 13 years ago in Sierra Leone, but the UK is currently training forces in three states that are anything but calm. General Sir Peter Wall, the head of the Army, said: “We have got three relatively new things which don’t involve significant numbers of people but nevertheless are pointers to the future: Somalia, Mali and also the training of Libyan militias for integration into the military.

“We learnt quite a lot in Iraq and Afghanistan about our lack of cultural understanding,” he continued. “Our people [are now] tuned to working with different... ethnicities who know more than we do about those parts of the world. We are [also] keen to continue our close relationship with the Kenyan armed forces. There are myriad other places [involving] smaller numbers of people with less sophisticated infrastructure.” In Africa this has seen the Grenadier Guards posted to Malawi, the 11 Signals Brigade operating in southern Africa and 102 Logistics Brigade helping in West Africa.

A plan to turn Libyan fighters into a security force was the wish of David Cameron and training will start at the Bassingbourn Barracks in Cambridgeshire early next year. There was a degree of trepidation about unfavourable publicity if some of the recruits became asylum seekers or engaged in extremism. But, as the recently departed head of MI5, Sir Jonathan Evans, has acknowledged, no one from the Libyan diaspora who went to fight Gaddafi brought terrorism? here.

Last month the Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan was kidnapped by fighters with links to his own government. After his release he said: “This would not have happened if we had an army.”

In Mali, the UK forms a part of an EU training team, while France retains military presence in a states from Chad to Djibouti, the Ivory Coast and Gabon. Mali, meanwhile, is a continuing concern for the Hollande administration. There have been a number of bombings while two French journalists, Claude Verlon and Ghislaine Dupont, were recently executed in Kidal.

The ability of al-Shabaab to reach beyond Somalia was illustrated in the Nairobi siege. UK Somalis have been returning home as democratic governance is established – the mayor of Mogadishu used to work at Islington council. But at the same time it has attracted British Muslims seeking jihad. There is a small UK team training African Union and Somali forces, while SAS and SBS members are on rotating assignment with the US-run Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa in Djibouti.

That the US is at the front of the fight against terrorism in Africa was shown in recent operations by Navy Seals in Somalia and Libya. The first – targeting Kenyan-born al-Shabaab commander Mohamed Abdikadir Mohamed – failed, but al-Qa’ida leader Abu Anas al-Libi was captured in Tripoli.

The biggest US military project in Africa remains Egypt, whose forces receive $1.3bn in aid from Washington every year. Some was suspended when civilians were killed by security forces after the overthrow of Mohamed Morsi, but many in Congress hope to use it as a bargaining tool to rein in the Egyptian military. The Pentagon also runs the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative (TSCTI), which operates civilian and military projects from Mali to Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, Nigeria and Tunisia. With Barack Obama’s much publicised shift in security focus to the Pacific Rim, the army stresses the importance of staying in Africa.

“If the world’s one remaining superpower is taking soft power seriously and the emerging one, China, is also starting on that path, soft power of a muscular variety can only get more traction,” said Robert Emerson, a security specialist. “Conflicts will not go away from Africa any time soon, but we are seeing major adjustments in dealing with them. It will be fascinating scene of competition for influence in the future.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments