Angela Merkel's unlikely journey from Communist East Germany to the Chancellorship

The German leader, who marks 10 years in office this weekend, is hailed by some as the most powerful statesperson in the world today, says our acclaimed Berlin Correspondent Tony Paterson. But how did this reserved pastor's daughter come to command the political stage? What will be her legacy in Germany and Europe? And can she survive the twin crises – an influx of refugees and a crumbling Eurozone – which threaten to tarnish her memory?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Angela Merkel has refused to give any special media interviews to celebrate her 10 years in power as Germany's first woman Chancellor. Following the terrorist attacks in Paris, and the fevered talks now being held in and between European governments, she may have no time to mark the occasion to the day, this Sunday. But if her timetable permits she will try to celebrate it, true to self-effacing form, in as low key a manner as possible.

For the most powerful woman in Europe, this means retiring to the small hideaway cottage she shares with her husband. The house lies at the bottom of a nondescript cobbled lane in the depths of the east German countryside near where she was brought up. There she will probably indulge herself by cracking open a beer and making one of her famous potato soups.

There is not a great deal to celebrate. For the first time in her career as German leader, the tide is beginning to turn against her. Since she opened Germany's borders to a projected one million refugees from Syria, Iran and Afghanistan in September, her popularity rating has sunk consistently. For most of her time in office, opinion polls have shown her to be one of Germany's most liked post-war leaders. But last week she was ousted from her position as the nation's favourite politician by her own conservative Interior Minister. Unlike Angela Merkel, he has pledged to slow the tide of migrants entering Germany.

Last Friday, Ms Merkel went on television and tried to restore public confidence. “The Chancellor has the situation under control and so does the government,” she declared. Yet only hours later the shocking news of the Paris terrorist attacks reached Germany. Unsubstantiated claims that one of the attackers entered Europe from Syria disguised as a refugee have helped to cast further doubt on Ms Merkel's open-door refugee policy. She now finds herself faced with growing demands from within her own conservative Christian Democratic Party for refugees to be turned back at Germany's borders. “Paris has changed everything,” insisted Marcus Söder, a leading Bavarian conservative earlier this week. “We must turn back refugees at the border,” added Klaus-Peter Willsch, one of her conservative MPs. “ If we don't do this, the Chancellor will end up being voted out of office.” Many have pointed to the irony that the 10th anniversary of the start of a reign which has earned her the title “Queen of Europe” may coincide with the beginning of what may well be her political demise.

Yet Angela Merkel's ability to bounce back is often underestimated. She has a habit of using her critics' failures to her absolute advantage, as she showed on the night she won the 2005 German election and went on to become Chancellor. Her Christian Democrats had hoped to do better, but in the end the party scraped home with just 35.2 per cent of the vote. The result was the party's worst general election performance on record, but it still left them with the largest number of votes.

Ms Merkel's weak performance prompted her macho opponent, Germany's then still ruling Social Democrat Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to belittle her during a prime-time television debate between the candidates after the poll. “You haven't a hope of becoming the next Chancellor”, he declared loudly. Angela Merkel famously said nothing at first. She just sat there pale faced, but slightly amused. Towards the end of the broadcast, she suggested to Schröder that with a “bit of humility” he might be able to accept that her party had won most of the votes. “Angie” as she was dubbed during the election campaign to the melody by Mick Jagger, had the last laugh. Two months later, on 22 November 2005, she was sworn in as Chancellor.

Angela Merkel has an uncanny ability to confound her mostly male political rivals. Being a woman undoubtedly helps her. The other factor often credited with giving her the edge over her still mostly West German contemporaries is her upbringing in Communist East Germany. She was born Angela Kasner in capitalist Hamburg in 1954. Her father, Horst, was a Protestant pastor who took the highly unusual step of moving with his wife Herlinde and Angela to Communist East Germany just a few weeks after his daughter's birth. At the time, only convinced Communists were opting to stay in Soviet-controlled East Germany. Horst Kasner, a devout Protestant, was not one of them. The family first lived in the small town of Quitzow before moving to the larger provincial East German town of Templin in 1957.

Templin is an ancient, 13th-century walled market town in east Germany's Uckermark region, an hour and a half's drive north-east from Berlin. Thanks to Germany's reunification, nowadays it is full of brightly painted and painstakingly restored 18th-century houses. The town calls itself the “Pearl of the Uckermark” and the tourist industry describes the surrounding region of woods and lakes as the “Toscana of the North”. But it was very different when the Kasners arrived. Much of the town was a bombed-out ruin, with streets made out of compressed sand. There were no cars, just one lorry, a delivery van and a few tractors.

Angela Kasner was brought up in the Waldhof housing area, a collection of 19th-century red-brick buildings more than a mile outside the town, which, then as now, was used as the Protestant church-owned St Stephanus home for the mentally handicapped. Horst Kasner ran the institution. At that time there was no Berlin Wall but people in the Uckermark were already beginning to flee to the West. The dearth of cars meant that many built rafts and went by river. Egbert Binkow, a former neighbour of the Kasners' recalls how the Waldhof was funded by the Western Protestant church and how its inhabitants obtained money and clothes from the West. The Kasner family lived in a privileged bubble that was largely isolated from the rigours of the Communist state. “Most of the children in Templin were told not to go and play there,” Mr Binkow recalled.

At home, the Kasner family played Monopoly and read Western newspapers, brought in under Protestant church protection. Agents of the despised secret police, the Stasi, were able to deduce that they watched Western television from the way the aerial on the roof of “Fichtengrund”, their two-storey house in the complex, was pointing. But they were unable to exert much influence.

Political discussions were held around the dinner table. Horst Kasner believed the basic idea of socialism was right but he disagreed with how it was being implemented in Soviet-controlled East Germany. Ms Merkel nowadays insists: “Very early it became clear to me that East Germany could not function.”

Nevertheless, the young Angela Kasner appears to have done much to feather her nest. She not only joined the Communist Free German Youth movement – which some critics still describe as the socialist answer to the Hitler Youth – but also learnt Russian, the language of East Germany's ultimate rulers.

Erika Benn, the 75-year-old Templin schoolteacher who taught Angela Kasner Russian at the Waldschule school, only a stone's throw from the family's home, said that the “incredibly industrious” Chancellor was a star pupil. “She used to learn vocabulary at the bus stop. She made no mistakes, she was reserved but not shy. I have never had such a gifted pupil since,” she added.

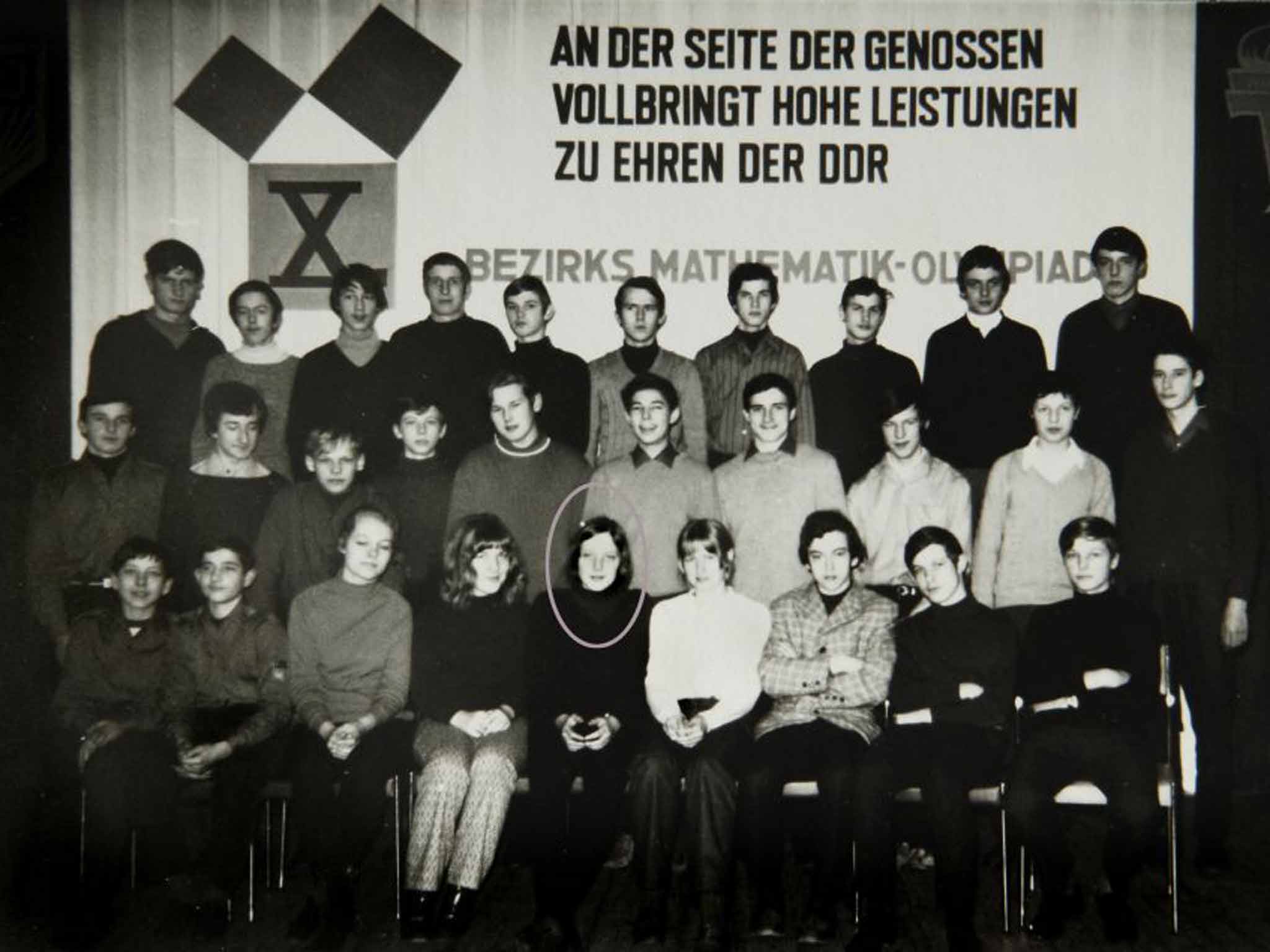

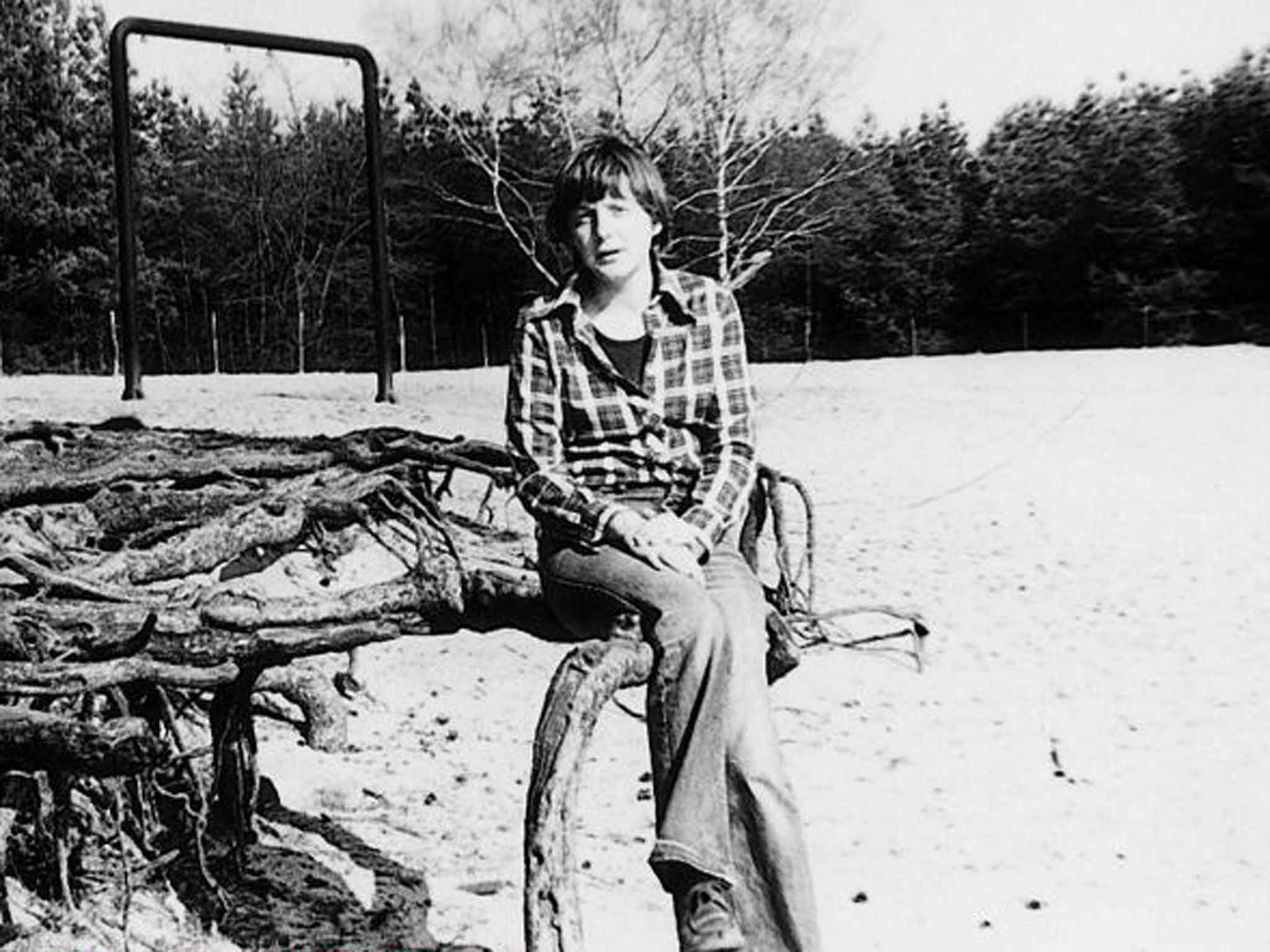

When she was 15 Angela Kasner won Templin's annual Russian language “Olympics” which guaranteed her fame throughout the region. After that she was unable to rid herself of her reputation as a school swot. Harald Löschke, a Templin resident who was in a parallel class to Angela Kasner in the 1970s, recalled: “She was never present when the youth of Templin went out drinking, when they went skinny-dipping in the lakes or listened to the latest pop songs on the radio.

“When we went on school trips she held scientific discussions with the teachers. That was way beyond our world. I never saw her with a man, she was mostly on her own,” he said.

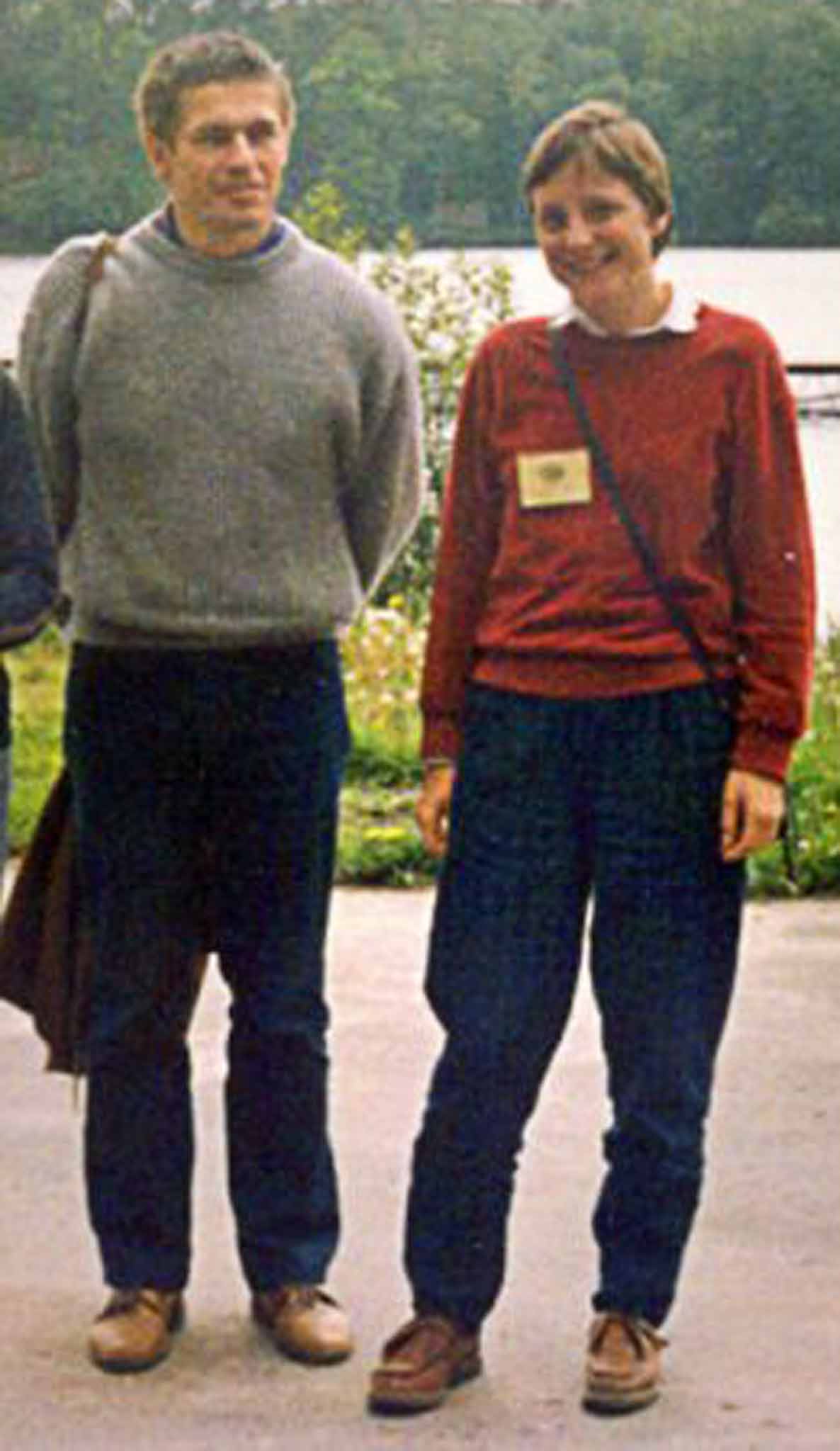

Like millions of East Germans Angela Kasner found a niche for herself which enabled her not only to survive Communism but also to benefit from it. She may intensely dislike being compared to Margaret Thatcher, her British counterpart, but both share a scientific background. Thatcher studied chemistry at Oxford. Merkel studied physics at Leipzig university and went on to complete a doctorate at East Berlin's Central Institute for Physical Chemistry in quantum chemistry. In 1977, while on an academic visit to the Soviet Union, Angela Kasner met and subsequently married fellow student Ulrich Merkel, the man who was to provide her with the surname she now holds. The marriage appears to have been a failure because the Merkels divorced in 1982. But Angela hung on to the name even after meeting Joachim Sauer, her reclusive physics professor husband, whom she married in 1998.

Angela Merkel was clearly too career minded to consider joining the growing number of East German dissidents who began protesting against Communist rule in the early 1980s. By late 1988, following Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's “Perestroika”, East Germany's brand of calcified hard-line Communism seemed completely out of touch to most of the rest of the world. But at Berlin's Institute for Physical Chemistry, she remained – albeit reluctantly – in charge of Communist “agitation and propaganda” (agitprop). At the same time she was living as an illegal squatter in a run-down flat in what is now the upmarket Berlin district of Prenzlauer Berg.

Had it not been for the fall of the Berlin Wall, Angela Merkel would have doubtless pursued an academic career as a physical chemist at one of East Germany's state-run universities. She seems to have clung on to this vision almost until the bitter end. In the summer of 1989, East Germany's Communist system was collapsing fast. Whole families of East Germans were fleeing west across Communist Hungary's by then porous border with Austria. Other East Germans were seeking refuge in West German embassies across eastern Europe. By the autumn of 1989, anti- Communist demonstrations were happening all over East Germany.

It was clear that the system was disintegrating and – with hindsight– that meant the Berlin Wall had to fall. But on the night of Thursday 9 November 1989 when it finally happened, Angela Merkel went to the sauna. Before heading off that evening, to sweat it out with some colleagues, she had watched the East German politburo member Günter Schabowski telling a television press conference that all East Germans now had the immediate right to travel to the West. That prompted Angela Merkel to phone her mother Herlinde, who said: “If the Wall falls we'll all go to West Berlin and eat oysters.” Her daughter replied: “ Perhaps it will happen soon,” and went off to her sauna.

It wasn't until Angela Merkel and her colleagues repaired to the Old Gas Lamp, a draught beer pub, for a post-sauna drink a couple of hours later, that she grasped the full enormity of what was happening. East Germany's once Kalashnikov-toting border guards had been forced to fling open the Berlin Wall. Thousands of East Berliners had started pouring through East Berlin's Bornholmer Strasse crossing point in the Wall towards West Berlin.

Angela Merkel rushed to join the throng. She remembers following an elderly woman “who had just thrown a coat over her nightdress” and was heading West. The Chancellor's recollections of that evening are somewhat confused. Together with thousands of East Berliners she ended up joining a giant party that was under way on West Berlin's showcase Kurfürstendamm boulevard that night. Later on, she remembers, she raised a toast to the fall of the Wall with a can of beer in “some stranger's” West Berlin flat.

That night many East Berliners partied until dawn on the streets of West Berlin. But this was not an option for 35-year-old old Angela Merkel. After all, she had to turn up for academic duty at East Berlin's Institute for Physical Chemistry in the morning.

She had no idea that day that her career as a scientist was about to come to an abrupt end. But the fall of the Berlin Wall was something Angela Merkel appears to have been waiting for consciously or unconsciously since she started becoming politically aware. “Immediately after it happened, three things became clear to me,” she told one of her biographers in 2009. “I wanted to get into parliament. I wanted German unification to happen quickly and I wanted a market economy.”

Like many East Germans in November 1989, she wanted to join one of the myriad of new political parties that were springing up in the suddenly Communist-free East Germany. She first considered the Social Democrats. Then she plumped for Democratic Awakening (DA) a liberal conservative grouping led by the East Berlin Protestant pastor Rainer Eppelmann, who today remains one of Merkel's staunch Christian Democrat MPs. Trained in agitprop, she became the DA's press spokeswoman and has since recalled, “It was chaotic but I had the feeling I was needed. The best thing was the fact that the political direction was not completely fixed.”

It wasn't long before the DA was swallowed up by East Germany's Christian Democratic Party, the eastern sister organisation to what was then “unification Chancellor” Helmut Kohl's ruling conservative party. By the time Germany was finally unified at the beginning of October 1990, Angela Merkel was a fully paid-up member of Kohl's Christian Democrats.

Kohl had already seen her potential. With reunified Germany's first general election only two months away, he badly needed East Germans in his party. Having a church family background, Angela Merkel was ideal. She was one of the few capable “Osties” around who were almost completely untainted by Communism or the Stasi. What's more she was a woman.

Within a year, Angela Merkel had become the first female East German minister in Helmut Kohl's cabinet. Less than a decade later, she ousted him as party leader.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments