Phil Toledano: Flirting with the cruel fates of life

Faced with the reality of his own mortality, celebrated photographer Phil Toledano has embarked on a new project exploring the many twists and turns his life could have taken, Abigail Jones writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I’m standing on a street corner in New York City’s Chinatown, looking for a guy who looks like the Phil Toledano I’ve seen online. It’s harder than it sounds, because the photographer – who’s known for shooting celebs like Alec Baldwin, Bill Hader, Alan Cumming and Jerry Seinfeld, as well as covers for The Atlantic, The New York Times Magazine and New York – recently turned the camera on himself, transforming his mischievous good looks into absolute catastrophe for his new book, Maybe.

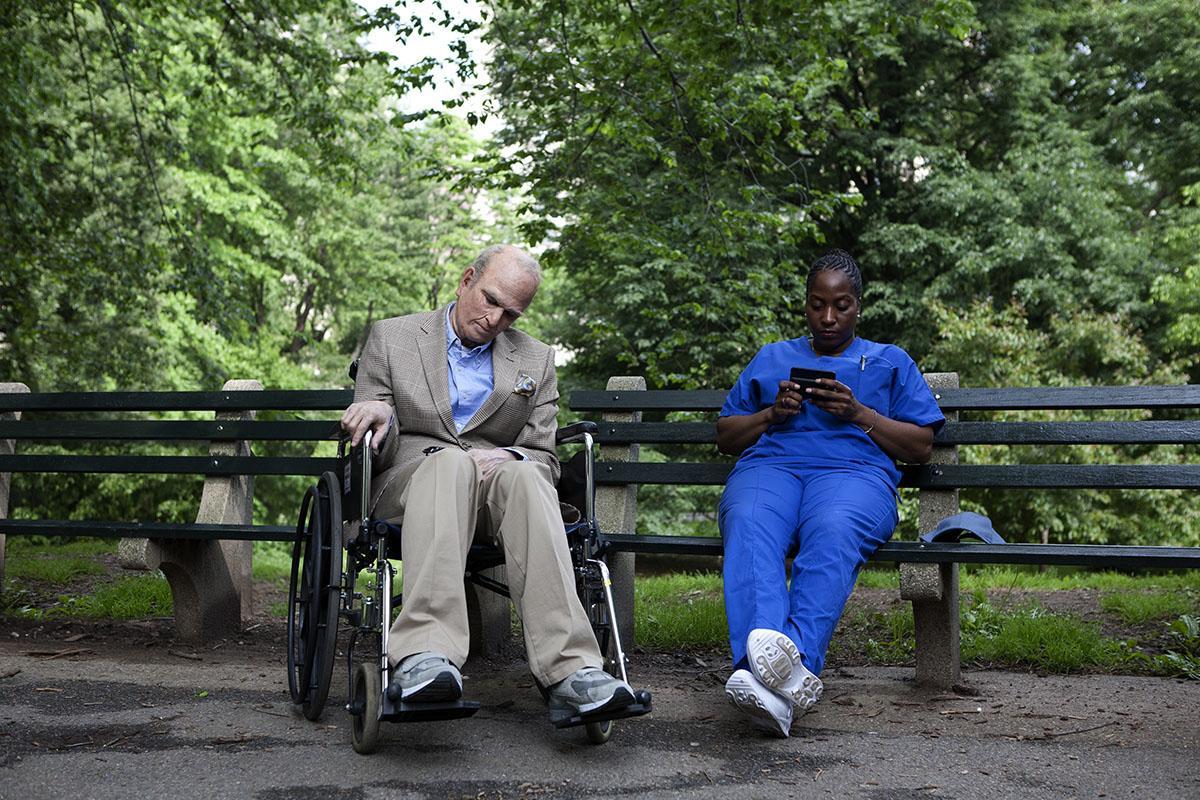

In one photo, Toledano is a sweaty, balding drunk. In another, an ageing creep with grey mutton chops. From wheelchair-bound, baggy-pant-wearing octogenarian to Bernie Madoff look-alike getting hauled off by the FBI, he spent the last three years marinating in the many ways his life could go horribly wrong. Toledano’s professional flirtation with cruel fates began in the mid-2000s, when his mother, father, aunt and uncle died in the span of a few years, leaving him terrified of his future.

Instead of retaining the services of a psychoanalyst like most neurotic New Yorkers, he chose to live out those fears in excruciating detail. He tested his DNA and learned he’s at risk for heart disease and obesity. Visits with psychics and fortune tellers unearthed more grim outlooks: alcoholism and suicide. He then teamed up with a makeup and prosthetics specialist, a stylist and actors to create masks and scenes that brought these depressing scenarios to life. The result is Maybe, a stunning look at the terrifying twists life might one day deliver. Toledano is known for being “photography’s big idea man”.

As collector and curator WM Hunt puts it, “He’s able to touch a popular place – and he’s not Anne Geddes. It’s not babies or kittens; it’s him. It’s that thing artists are really able to do when they mine themselves and they’re their own primary resource. He’s able to work in the vernacular without being a snob or common.”

Toledano, 47, was so convincing as a stroke victim and an obese man in an ill-fitting button-up that I almost forget whom I’m looking for on the sidewalk. I notice a crossing guard. A stuffed animal bunny with star-shaped sunglasses hangs upside down above him, dangling from thick telephone wires and gently swaying in the breeze. It’s a moment Toledano would have appreciated – lately, he’s been experimenting with Boomerang, an app that creates four-second videos that play on a loop – so I raise my iPhone to take a video when it suddenly rings. “Is that you taking photos across the street?”

I look up and see Toledano waving a block away. He’s wearing dark jeans, a blue T-shirt and Stan Smiths with yellow laces. He greets me with a huge smile, a British accent and a few quick pleasantries. Then, with hardly a glance in either direction, he bolts out into traffic, toward the park across the street. I hustle after him. We’d agreed to spend the morning at the site of his latest pet project: #ChinatownExercisers, a collection of Boomerang videos of men and women shifting their arms, kicking their feet and balancing on one foot on the playgrounds of Chinatown.

It may sound dull, but Toledano’s clever use of Boomerang turns that woman gently moving her arms up and down into a GIF of someone furiously flapping her arms as if she’s about to take flight. The videos are comical, but they also capture something authentic and unique about New York City. “In some ways, I think [these videos] represent the last vestiges of what New York really was,” he says as he waltzes through the playground, where about a dozen adults stand around “exercising”.

There are no Lululemon zip-up hoodies or “Soulhampton” T-shirts out here – the exercisers wear everyday clothes: suits, jeans, blouses. Some are barefoot. It’s around 9 am, and all around them Chinatown roars with life: Car horns blare; trucks barrel past. A cacophony of foreign languages and string music from a street performer waft through the air. “It was an immigrant culture for centuries. You think about the early 1900s and Ellis Island and particularly the Lower East Side – oh! Here! ”

He stops to Boomerang. “See this woman? Full business suit! She’s going to work after this,” he says, pointing to a woman in a black skirt suit standing beneath a blue play structure, shoes off, purse on the ground, pumping her knees in place. “Oh, hang on, that’s really good! ”

He bolts toward an old man reaching for two playground rings with trembling hands. “I just wanna lift him up,” Toledano says. A moment later: “He got it! Amazing. See that? He must be in his 90s.”

Toledano was born in London, walks as briskly as a born-and-bred New Yorker and stops short with the frequency of a toddler. Whether he’s mid-sentence or mid-crosswalk, he aims his iPhone at everything: clouds, pigeons, a leather-clad 20-something. “See that, the smoke in the sunlight? It’s beautiful!”

After filming a few more Boomerangs, we head to Café Henrie, which Toledano claims has the best egg sandwich on the planet. It’s also probably one of the most Instagram-ready restaurants in the city: polka-dot wallpaper, pastel tables, turquoise pipes and a florescent pink light illuminating the way to the restroom. We sit down at a tiny, pale pink table and order smoothies as Toledano starts selling me on the egg sandwich. “It’s in a brioche roll with sliced hard-boiled egg. It’s not like a New York egg sandwich, but – see!” he says, interrupting himself. “I don’t understand why people take pictures of food. It totally eludes me. Look! Watch! It’s fascinating.”

I turn around and see a young woman carefully photographing her meal with her iPhone. (This might be that photo.) “I just find food pictures totally uninteresting,” he says. “There’s so many other things I’m interested in looking at.” Muk-bang is one of them, a social trend of Koreans watching others binge eat on camera. “They have YouTube channels of them eating, and millions of people – you’ve gotta watch it!”

Later, not long after the young woman leaves, a lanky guy walks over to her table, suspends his phone above her dirty plate and takes a photo of the half-eaten meal. “Look!” Toledano says. “He just took a picture of her empty food! That guy just took a picture of – wow!”

I say, “Do you think she’s a famous Instagrammer or something?”

“Interesting! Maybe,” he says. “I had an amazing reverse star-spotting 10 years ago. I was waiting in the French Roast [coffee shop] on the west side, and I was sitting next to Sam Shepard. The guy I was waiting for came up to Sam Shepard and said, ‘Are you Phil Toledano?’”

A decade ago, the name Phil Toledano may not have sparked much interest in the art world, but as photographer Doron Gild says in The Many Sad Fates of Mr Toledano, a new documentary by Joshua Seftel about the making of Maybe, “Anybody who’s in our industry knows who Phil Toledano is, but he has no idea of the fact that basically everybody thinks he’s a genius. ”

“He’s charismatic and fun and remarkably unfucked up about it,” Hunt says. “There’s something irresistible about him, and that doesn’t happen very often these days. I’ve dealt with lots of artists over the years, and the ego thing is there, always. Some are threatened if you don’t feed their ego. They resent it and withdraw, and they’re hurt. They act like babies. Then you get Phil, who has a really healthy ego and is a complete narcissist, but you don’t mind it. You’re happy to get on board and roll along with him. That’s unusual.

Hunt adds: “He engages you in a way that is unlike anyone I can think of who’s working in the art world now. I really can’t think of anyone else who’s charming and funny and moving and straightforward.”

As a boy, Toledano wanted to become an astronaut. Or a doctor who could fly. He also dreamed of moving to New York City, where his father grew up. “I remember at 10 or 11 just thinking I’ve had enough of England,” he says. “England in the Eighties was a country of ‘Why?’ Why would you do that? New York is a place of ‘Why not?’ I love that.”

He went to Tufts University, outside of Boston, where he studied English literature and spent late nights at a diner in Harvard Square, getting high and eating hot dogs at 3 am. After graduating, he moved to Paris and interned at a cousin’s software company. His job: testing software for glitches. “I developed this fictional tropical bowel disorder, which would entail me going to the bathroom four or five times a day and having a five-minute nap with a roll of toilet paper behind my head.”

After a stint at another cousin’s software company and a halfhearted try at photography (“I didn’t have the balls – you have to have such strength to be an artist”), he moved to New York City and spent the next 12 years in various advertising jobs, from copywriter to art director and creative director. Along the way, he met his wife, Carla. “She used to come into my office and brief me. She was strategy, and I was creative, and she’d come in and go red [blushing],” he says, smiling. “And then I’d go, ‘Oh, look, you’re going red!’ Because I’m such a dick, I’d point it out.”

They live in Chinatown with their six-year-old daughter. Raising kids in New York City can be chaotic, even absurd – schools like apartment buildings, apartments the size of closets, closets the size of suitcases – but Toledano says it’s “genius.”

“There’s something amazing about New York kids,” he says. “They’re smart and savvy. They’re awake in a way other kids are not awake. When you see kids from wherever – Ohio – they’re not awake because they don’t have a sense of how the world works or who’s dangerous and who’s not or how to get around.”

At 35, Toledano realised that if he stayed in advertising, he’d probably end up with a house in the Hamptons and “a job relaunching the Today Sponge or Always with Wings,” he says. “You’ve only got one go at the whole thing, and surely it’s worth trying something I think I might be better at,” he says. So he quit and became an artist.

Over the past decade, he’s published seven books and three retrospectives, shot covers and photos for some of the most influential magazines on the newsstand, and explored in his work everything from sex and tech to plastic surgery and the joy and agony of family. In Phonesex (2006), his portraits of phone sex workers reveal the mundane truth behind all that carnal theatre: an obese woman in a wheelchair, a soccer mom look-alike, a 60-year-old with a cultural anthropology degree and 25 years of marriage behind her. In the two-minute video “The Louniverse,” eerie, Interstellar-esque music plays as we watch close-up shots of Loulou’s face appear against a black backdrop, her eyes flitting back and forth, mesmerised by whatever is happening on the iPad in front of her. It’s like witnessing the discovery of childhood and, simultaneously, its obliteration.

When Toledano’s mother died in 2006, he discovered that she’d been hiding a vital truth: His 97-year-old father – once a dapper actor and artist – had lost his short-term memory. Days With My Father (2010) chronicles Toledano’s relationship with his father in the final years of his life. The photos are unfussy yet powerful – his father looking in the mirror, seemingly stunned at his haggard appearance; words his father scribbled in a notebook (“Where is Philip? Ralph? Everybody?”).

A few years later, The Reluctant Father (2013) documented Toledano’s journey of becoming a father, from dread to unbound love. When I Was Six (2015) offers a heartbreaking glimpse into the short life of Toledano’s sister, Claudia, who died in a fire when she was nine. Toledano’s parents rarely spoke of her, but 40 years later, while cleaning out his father’s apartment after he died, Toledano discovered a box of Claudia’s things his parents had saved – photos, toys, handwritten notes, clothes.

“It took me a year to do the still-life pictures,” he says, his eyes watering. “It was just – intolerable…. But at the end, I felt grateful. To my parents, that they managed to go on in a situation where so many people don’t. That they gave me the beautiful life that they did. That they didn’t bury me with my sister. I felt grateful for the opportunity to touch her, and then, in some small way...” He shifts his glance to the window. Perhaps in some small way, all of this is Toledano’s way of freeing himself from his mother’s sudden death, his father’s protracted decline, his sister’s tragedy and his fears about what might happen to him.

“That project is not about death at all. It’s about the sharp right angles that life has in store for you,” he says. “It’s easy to look at [Maybe] and go, ‘It’s a narcissistic exercise of a hypochondriac’... But on the other hand, I’m talking about something we all think about: your life going sideways.”

After brunch, we wander back to the playground. Toledano tells me about one of his next projects, a comical skewering of the art world in which he takes on the notion that you’re nobody until somebody says you’re somebody. He tracked down people with the same names as the bold-faced names of the art world, then interviewed them on camera, asking them to talk about how great he, Phil Toledano, is. “So Cindy Sherman is a shrink from New Jersey, and she talks about how she thinks I need professional help. Chuck Close is a 17-year-old kid, so he just didn’t know what to say at all. He was really weird and awkward.”

On the edge of the playground, Toledano spots dozens of pigeons flapping and pecking around a small tree. He steadies his iPhone, bends his knees and runs toward them, capturing their dramatic escape on camera. He checks his Boomerang of that, then spends the next 20 minutes scaring the pigeons away and waiting for them to return. “They’re so obliging! ” he quips. “Low-paid – bread crumbs.”

Eventually, we say goodbye and head off in different directions. Half a block later, I turn around and see him pause near the stairway leading down to a subway station. A moment later, though, he’s walking back to the corner, back to the pigeons.

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments