The mystery of Lebanon's missing thousands

Relatives of those who disappeared during the civil war want answers and hope that a new commission will help

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wadad Halwani's husband was taken just as the family was about to eat lunch in September 1982. Secret police came to their house in Beirut and said they needed to question her husband, Adnan, about a traffic accident. She had no idea it would be the last time she saw him.

Nearly 32 years later, she is still fighting to know what happened. "It's not just about the disappearance of my husband. It's an issue that touches about 17,000 people and their relatives," she said, citing the estimated number of people who went missing during Lebanon's civil war. "It's a national cause."

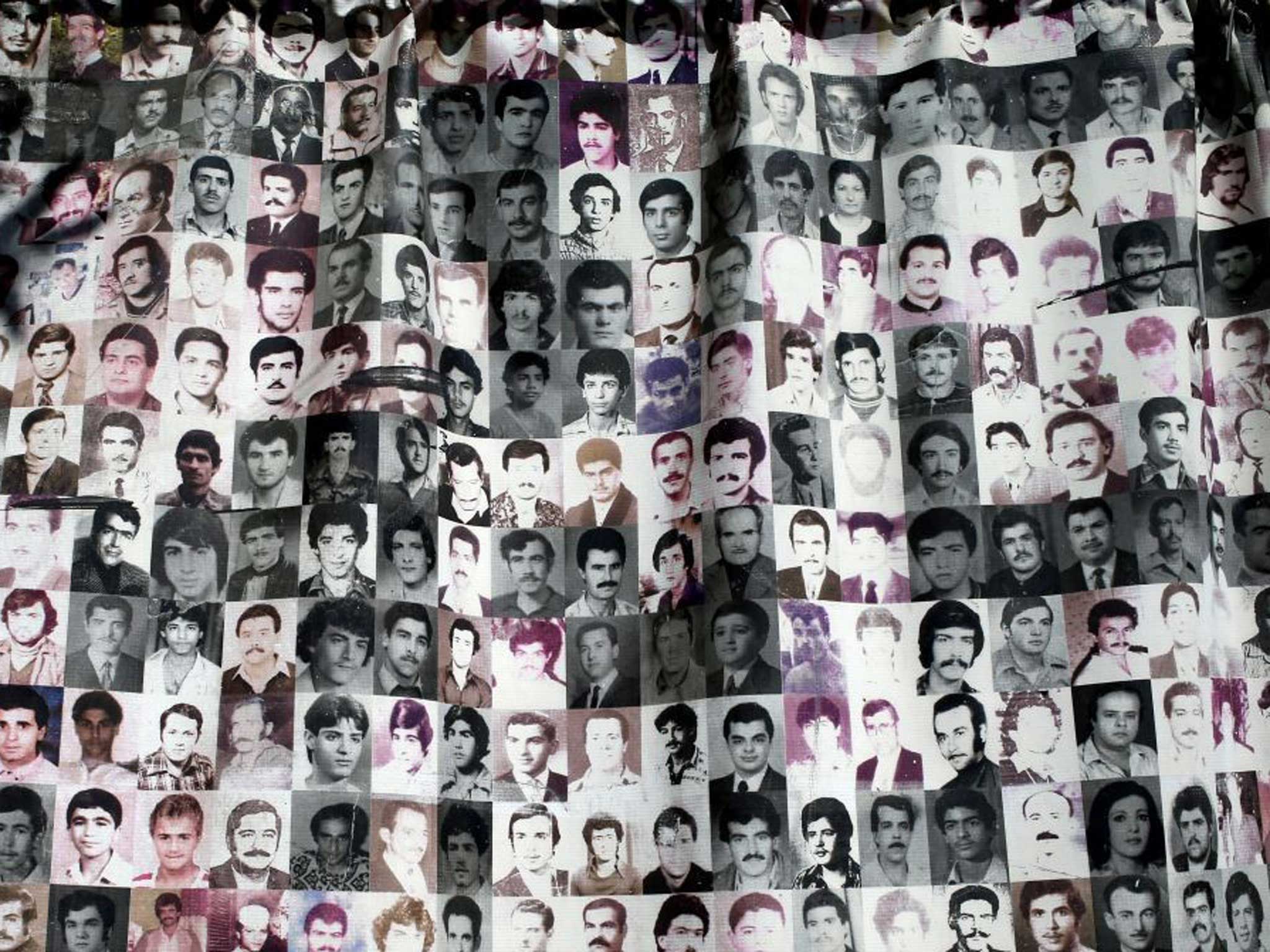

Later that year, Mrs Halwani co-founded the Committee of the Families of the Missing and Disappeared in Lebanon and has constantly lobbyied the government for answers. Since 2005, a group of women have camped out in a park below Lebanon's parliament. The women carry pictures of their loved ones; their protest tent is a sea of missing faces.

Almost three decades after the start of the Lebanese civil war, some information finally appears to be forthcoming. Last month, the Shura Council, Lebanon's upper house of parliament, ruled that families should be able to obtain copies of all documents from a 2000 commission of inquiry. But more importantly, the ruling finally acknowledged that families have the right to know what happened to their loved ones. Mrs Halwani called it a "large victory" for the relatives of the missing.

There has been resistance from the government, which said that addressing the issue of the disappeared will only reopen old wounds and cause civil strife. The International Center for Transitional Justice, an NGO which seeks accountability for war crimes and human rights abuses, called the country's refusal to face its past "state-sponsored amnesia".

The reason for such a policy is that the perpetrators of such crimes are still in power, argued the MP Ghassan Moukheiber, who tomorrow will submit a bill to set up a national commission for the disappeared. "Many political parties had their own militias, and have been responsible for killing. Many of these people now running Lebanon have their own skeletons in the closet," he said.

Mr Moukheiber hopes the commission will also be able to create a mechanism to deal with the issue of opening up mass graves. Realising the political sensitivity of the subject, NGOs are currently lobbying for protection of the sites. It is estimated that some 17,000 people disappeared during the 1975-90 civil war in which the country was overrun by militias vying for power and more than 150,000 died.

"Maybe it's too early for Lebanon. Maybe we need to wait more," said Justine de Mayo, founder of Act for the Disappeared, an NGO trying to raise awareness of the issue. "But as a society, if we don't address this issue, we can't look towards the future."

The government never conducted an official investigation into the civil war. The 2000 commission, composed solely of security personnel, issued only a two-page report. It said there were only 2,046 missing – all presumed dead – and advised families to declare that their relatives had died. The government has been encouraging relatives to move on since 1995, when it created the possibility to declare those missing for more than four years as legally deceased. But many feel that registering their loved ones as dead means they will never find out what happened.

Those most optimistic about a possible return of their loved ones are the relatives of between 300 and 600 Lebanese who disappeared after being detained in Syria. Relatives are convinced they are languishing in prison in Syria, now caught up in the new wave of disappeared being created by the Syrian crisis.

Some have resorted to paying for tip-offs. Marie Mansourati said she had spent $200,000 (£120,000) on finding her son Daniel. He was abducted when the family was visiting Damascus in 1992, two years after the civil war ended. The 30-year-old had been a member of a Christian militia, whose leader confirmed to Mrs Mansourati that he was in custody in Syria. She pays up to $500 a time for information, but is always disappointed: "When the thieves go, the liars arrive. When the liars go, the thieves arrive."

However, she refuses to give up hope, despite several reports that her son died in the 1990s. "He is alive and in prison in Syria," she insisted. "I am sure he is alive."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments