Lessons from the Yom Kippur war, 50 years on – and why it matters today

As the world holds its breath and leaders meet in an attempt to stop the Israel-Gaza conflict from escalating, author Uri Kaufman revisits the Yom Kippur war, which brought the world close to nuclear war, and looks at what stopped it

It was 50 years ago, on 6 October, and I was a nine-year-old boy running around in the New Haven synagogue in Connecticut where my father was the rabbi when I came upon a group of men huddled in a corner. Children are not expected to fast on Yom Kippur, but that did not reduce my embarrassment the year before when I had been caught eating an ice cream. My childish mind wondered if the gentlemen were also engaging in similar secret culinary infractions.

But as I got closer, I could see how serious their faces were as they huddled around a transistor radio. Dazed and in shock, they were listening to the news of a surprise attack on Israel by the combined armies of Egypt and Syria. Launched on the Jewish holiday, the Arabs went to war to reclaim the lands they had lost in the 1967 six-day war.

The world would look on in horror for 18 days as the parties engaged in some of the largest tank battles in history. By the time the conflict, now known as the Yom Kippur war, ended, an estimated 20,000 men were dead. The global economy was shaken to its foundation by an oil embargo, while the superpowers had been pushed to the brink of a third world war.

Many people will have only heard about the events of October 1973 a week last Saturday when, on the 50th anniversary of the attack, Hamas invaded Israel, killing more than a thousand civilians and abducting more than 100 hostages in Gaza. We are now watching the consequences of those terrorist acts, and tomorrow’s history books are poised for the next chapter of the region’s complex story.

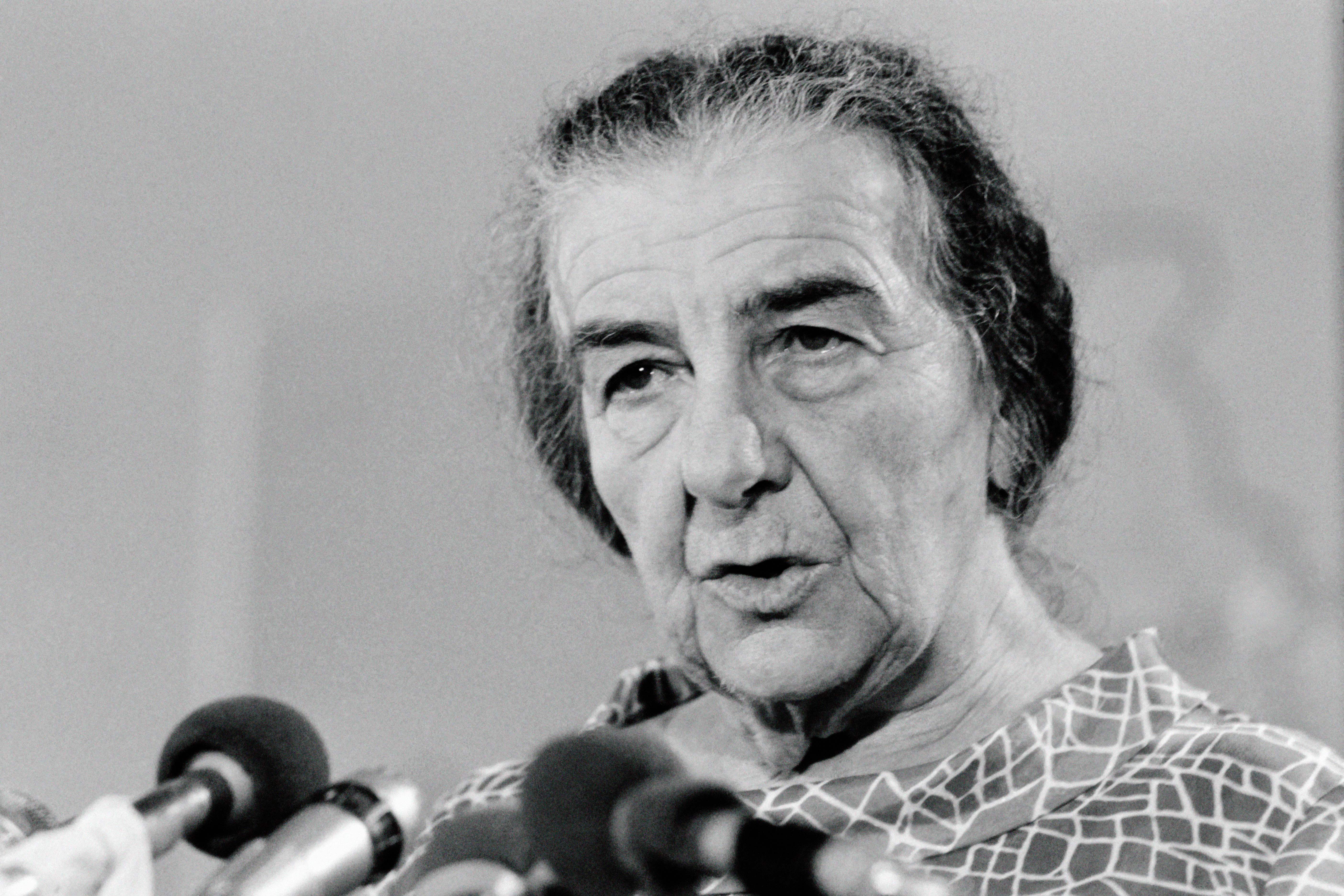

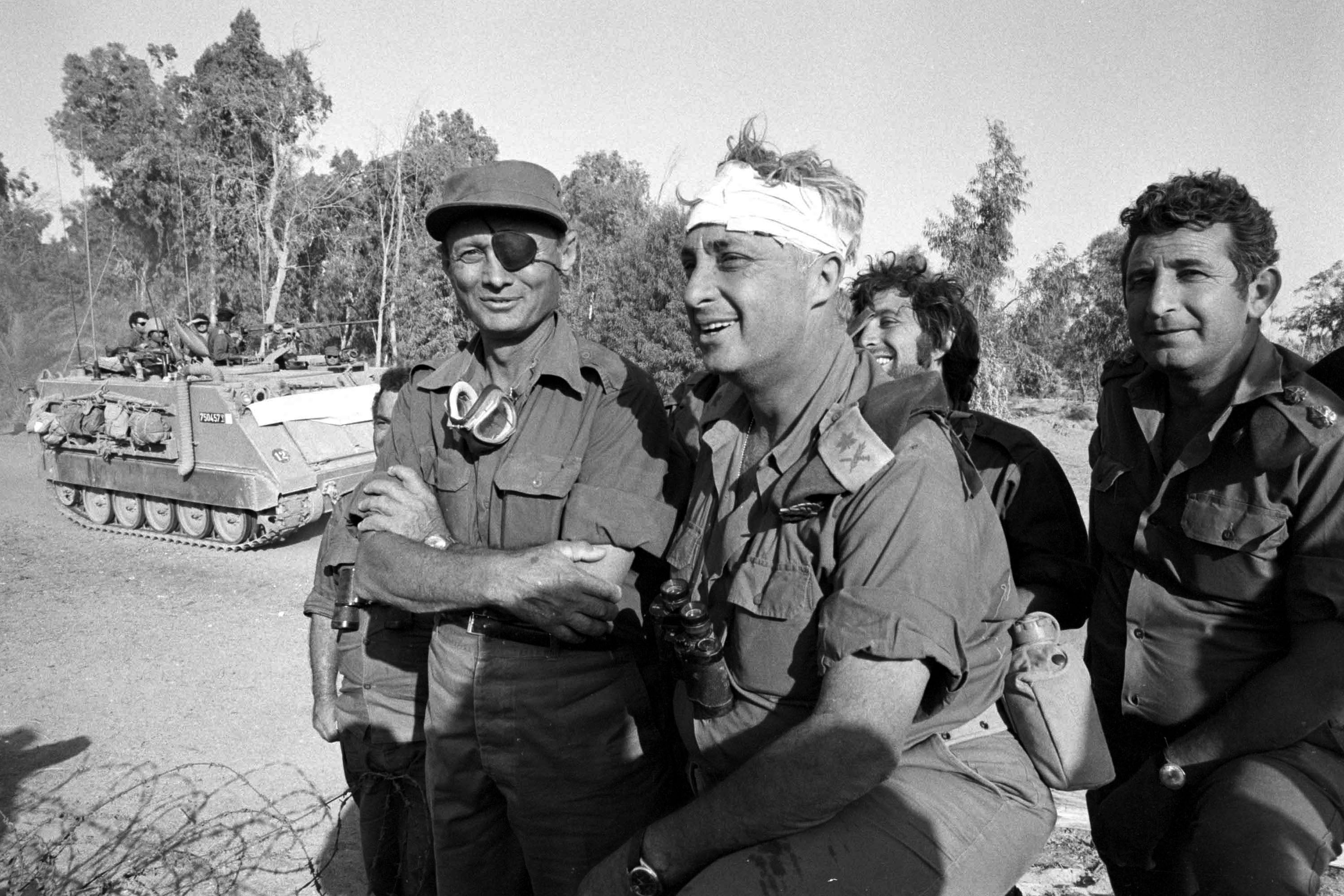

It took me 20 years and a team of researchers from around the world to understand the events of October 1973. The twists and turns that unfolded then surpassed anything that a novelist could have ever contrived. There was the swashbuckling Israeli general, Ariel Sharon, who won the key battle of the war by launching an unauthorised attack in direct violation of his orders. Also, the one-eyed defence minister with a bipolar personality, Moshe Dayan, who suffered a partial breakdown in the desperate early days and advised readying nuclear weapons. And there was prime minister of Israel Golda Meir who, siding with more cautious ministers, told Dayan to forget about nuclear weapons and led her nation to an improbable victory. The war continues to cast a shadow over the region and the world.

The two attacks, half a century apart, were also the result of catastrophic failures of intelligence. Today, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu is under fire for ignoring warnings from Egyptian intelligence that “something unusual, a terrible operation” was imminent. Fifty years ago, Meir had also ignored a warning, then from King Hussein of Jordan who had told her that a war with Egypt and Syria was imminent. While she went on to win the war, this fatal error would lead to her eventual resignation.

So what led to such a failure of intelligence in 1973? We now know that Israeli military planners were guided by something called the conceptzia, or simply “the concept”. In its simplest form, the concept said that Syria would not go to war without Egypt and that Egypt would not go to war until it received a fleet of advanced Soviet fighter jets that they knew could neutralise the Israeli Air Force. Since those fighter jets were not scheduled for delivery until 1974, the Israelis figured they were safe in 1973.

They found out the hard way that Anwar Sadat, president of Egypt, had conceptzias of his own. Soviet-made surface-to-air missiles offered a partial solution to the problem of the Israeli Air Force. And with a failed coup attempt, a bankrupt economy, and restive officers aching to avenge the humiliating loss of 1967, Sadat concluded in 1973 that he had to go to war with the army and weapons he had.

To fool the Israelis, the Egyptians held war exercises along the Suez Canal, practising every aspect of an invasion of Sinai. The constant manoeuvres were carried out not just to maintain readiness but to conceal intentions. This was a tactic learned from the Soviets, who fooled Western intelligence agencies by regularly training along borders. Most of the time they demobilised and went home, but occasionally the drills turned into surprise attacks.

The brilliance of the tactic lay in the fact that only a few people at the very top needed to know that an invasion was afoot. Likewise, once Egypt mobilised along the Suez Canal, it was impossible for Israel to determine whether the troops were there to train or to go on the offensive. In 1973, between 1 January and 1 October, Egyptian reservists were called up and sent home no fewer than 22 times. On the 23rd, they were ordered to head over the canal. Only a handful of senior officers at the very top knew that a war was in the offing, and of the 8,000 Egyptian troops that Israel captured in the war, only one knew about the planned attack on 3 October. Practically all the others found out on the morning of 6 October, the day the war began.

In the opening hours of the war, Israel’s shock was total. Its citizen army of reservists needed 48 hours to mobilise. The lightly defended defensive line crumbled in their absence. The Egyptians only advanced a few miles into the Sinai Peninsula, but the Syrians threatened heavily populated northern Israel. On the first day, the Israelis lost more than 200 tanks, or more than 10 per cent of their entire arsenal. The loss of fighter jets was almost as bad. At that burn rate, the Israeli Army would succumb to the tyranny of arithmetic in less than two weeks.

Dayan advised pulling back 30 miles from the Suez Canal, to the easily defensible Mitla and Gidi Passes. Meir rejected the advice and ordered the army to dig in and fight. Events proved her right. The losses eased, and the line stabilised just a few miles from the Suez Canal, thereby setting the stage for a later counterattack. Meanwhile, Meir had to decide what to do with her only spare division, which was tasked with defending Jerusalem from a potential attack by Jordan.

She gambled that King Hussein would stay on the sidelines and ordered the tanks north to the Golan Heights. For two nerve-shattering weeks, the nation’s capital stood naked to attack. But the Jordanians left the border quiet, fearful that if they made a move, the Israeli Air Force would lay waste to the kingdom, and the division sent north pushed the Syrians back to their original line.

The hardest decisions were left for last. By 16 October 16 1973, the Israelis only had 650 tanks left along the Suez Canal. Meir ordered 400 of them to cross it. Dayan warned that if the force west of the canal was cut off, the Israelis would find themselves fighting on the outskirts of Tel Aviv. But the Israelis crossed the canal and charged southward across the Egyptian heartland. The goal was to cut off three roads taking much-needed supplies to the 30,000 men in the Egyptian Third Army stationed east of the canal.

As the Third Army’s lines were reduced one road at a time, Sadat panicked and pleaded with his Soviet allies to impose a ceasefire. Washington – Israel’s patron and sole weapons supplier – was only too happy to oblige the Soviets and so aid the rescue of the Egyptian army. America was now labouring under an oil embargo, and secretary of state Henry Kissinger was told that while Second World War rationing had only reduced American domestic demand by six per cent, the ongoing embargo threatened to reduce supplies by 18 per cent. During the Cold War, ceasefire agreements typically took years to negotiate, but feeling the urgency, Kissinger flew to Moscow and agreed upon a ceasefire in just four hours.

Meir would have none of it. She ordered her men to defy Washington and keep going, surrounding the Egyptian Third Army a day after the UN Security Council ordered the Israeli army to stop. The Soviets were outraged. Throughout the Cold War, the fear was not a repeat of the Second World War, where one power brazenly invaded another. The fear was a First World War scenario where complicated alliances turned a regional conflict into a global one.

In gaming this out, military planners had long identified the Middle East as the modern successor to the Balkans. Fortunately, neither Washington nor Moscow wanted to fight a third world war over Egypt, and the two sides stood down, the crisis eased – and the Israeli army maintained its siege of the Egyptian Third Army. They refused to release the stranglehold on the Third Army until Cairo agreed to create wide demilitarised zones that rendered future surprise attacks from their army impossible. The Egyptians and Syrians were faced with a stark choice: make peace with losing the 1967 lands or make peace with Israel. The Israelis had won the Yom Kippur war.

The war officially ended when a second ceasefire agreement was proposed by the UN and brokered by the USA and the Soviet Union on 24 October 1973. This paved the road to agreements negotiated over many years between Israel and Egypt. Sadat made peace in 1979 and received the Sinai Peninsula. Syria refused to make peace and never received the Golan Heights.

Say this for the Arabs of 1973: they lost the war, but they regained their honour. In remembering the courage on all three sides – Israel, Egypt, and Syria – Ariel Sharon called it a “soldier’s war”. What occurred in Israel 50 years and a day later was no soldier’s war. It was a terrorist massacre.

Hamas caught the Israelis off guard much in the way the Egyptians did in 1973 and had trained along the border fence and stood down numerous times. A senior Hamas official named Ali Baraka said recently on Russian television that only a handful of Hamas’ senior leadership knew that on 7 October 2023, they would be ordered to break through the fence and go on a murderous rampage. No one believed that Hamas would deliberately cut off its only economic lifeline.

So why do it? Because, like Anwar Sadat, it had conceptzias of its own. The political leader of Hamas and founding member of its military wing is 60-year-old Yahya Sinwar, a mass murderer given four consecutive life sentences in an Israeli court for killing five Palestinians suspected of collaboration. He would have spent the rest of his days in jail, but he was freed in a 2011 prisoner swap, which saw Israel release 1,027 Palestinian prisoners to obtain the freedom of a single Israeli named Gilad Shalit, a kidnapped soldier who had been held for five years.

The Israeli prime minister who approved the deal was Benjamin Netanyahu. If Netanyahu would free more than 1000 Palestinian prisoners to obtain the release of just one hostage, Sinwar may very well have figured, imagine what he would do if Hamas held over a hundred.

Sinwar may be about to receive a lesson in what happens when your conceptzia turns out to be wrong. The Israelis are now determined to remove Hamas once and for all, and it is impossible to say at this early stage who will ultimately assume control of Gaza. Although one idea that has been floated has been of using a multinational Arab force to reinstall the Palestinian Authority, the governing body headed by President Mahmoud Abbas, which now rules the West Bank from Ramallah. Whatever the outcome, the old order is finished. Gaza is likely to become a ward of the international community, living, like the residents of Idlib in northern Syria, on humanitarian assistance.

Meir wrote in her memoirs that the circumstances that led to the Yom Kippur war would “never ever recur”. For 50 years she was right. Today, we are left to watch how the sequel to the Yom Kippur war will unfold half a century later and trace the lines from yesterday’s battlefields to see where they could lead to tomorrow.

‘Eighteen Days in October: The Yom Kippur War and How It Created the Modern Middle East‘ by Uri Kaufman is out now, published by Macmillan

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments