Suez Canal blocked: A brief history of the Egyptian trade route and the Ever Given stranded in its waters

Man-made waterway opened in 1869 but grand vision of passage to India dates back to pharaohs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The grounding of the Golden-class container ship the Ever Given in the Suez Canal, causing the vessel to drift sideways and block both north and south-bound freight traffic, has brought sudden international attention to the celebrated waterway connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea.

The 120-mile man-made passage was originally constructed by the Suez Canal Company between 1859 and 1869 but the idea’s origins go back as far as Ancient Egypt, the goal the same then as it was for the Victorians: to open up global trade between the east and west.

Pharaoh Senusret III is thought to have built a precursor connecting the Red Sea with the Nile River as long ago as 1850 BC, while the later Pharaoh Necho II (610-595 BC) held similar ambitions that went unrealised until the Persian conqueror Darius (522-486 BC) completed it and proclaimed: “When the canal had been dug as I ordered, ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia, even as I intended.”

Herodotus reported that 120,000 men were killed in Necho’s attempt and that Darius’s finished “Canal of the Pharaohs” between the Nile and the Great Bitter Lake was broad enough to allow two galleys to pass each other with their oars extended without colliding.

It was restored by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in 270 or 269 BC, before the gradual receding of the Red Sea coupled with persistent accumulations of silt from the Nile meant its use fell away over the centuries.

Read more:

While Venetian traders revived the idea of carving out a passage to India in the early 16th century, Napoleon Bonaparte is credited with conceiving the first modern canal after his conquest of Egypt in 1798.

But the French commander was incorrectly counselled by his cartographers and engineers that the Red Sea lay 30-feet higher than the Mediterrean, meaning the Nile Delta would be flooded should an artificial waterway be built, dissuading him from pursuing it.

That error would be put right after a team of experts including Paul-Adrien Bourdaloue, Robert Stephenson and Alois Negrelli reviewed the matter in 1847, paving the way for French former diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps to negotiate an agreement for the grand project with the Egyptian viceroy, forming the Suez Canal Company in 1854.

He commenced work on his hugely ambitious channel, running from Port Said to Port Tewfik, three years later against fierce resistance from the British (concerned about the impact on its lucrative India trade routes), which saw our national press brand the canal “a flagrant robbery gotten up to despoil the simple people” and De Lesseps engage in a war of words with prime minister Lord Palmerston and even challenge Stephenson to a duel of honour after he criticised him in parliament.

Egyptian peasant labourers were forced into taking part in the construction under the threat of violence, using picks, shovels and their bare hands to haul out the earth before the country’s ruler, Ismail Pasha, outlawed the practice in 1863, forcing De Lesseps to adopt high-tech steam and coal-powered shovels and dredgers instead. Seventy-five million cubic metres of sand would ultimately be shifted over the decade of building work, three quarters of which was moved by heavy machinery.

An opening ceremony was held on the evening of 15 November 1869 in Port Said, with illuminations, fireworks and a banquet aboard the Pasha’s yacht. Emperor Franz Joseph I, France’s Empress Eugenie and the Crown Prince of Prussia were all in attendance.

Interestingly, French sculptor Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi had approached De Lesseps that year with his idea of erecting a 90-foot tall statue of a woman bearing a torch to serve as a lighthouse guiding ships into the canal at its mouth. “Egypt Bringing Light to Asia” was rejected by the engineer but, undeterred, Bartholdi finally unveiled another version in New York City in 1886, an icon that became known as the Statue of Liberty.

The Suez Canal became a centre of conflict between Britain, France and Israel 87 years after it opened when Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised it on 26 July 1956. His country had gained its independence from the British Empire in 1922 but an occupying military force continued to oversee the canal to secure Britain’s commercial interests and had opposed the building of the Aswan Dam.

The tripartite forces advanced into Egypt on 29 October to regain control before attracting widespread condemnation from the international community, including the US, UN and the Soviet Union, who threatened nuclear retaliation.

British prime minister Anthony Eden, also under pressure from protesters at home, was forced to order a retreat and ultimately resigned in humiliation and ill health.

The canal would next make news during the Six Day War between Egypt and Israel in 1967, when it was closed and blocked at either end by scuttled ships and mines.

At the time of the shutdown, 15 freighters were caught in the middle of the canal and would be forced to wait there for an astonishing eight years, becoming known as the “Yellow Fleet” after the desert sands that caked their decks.

Until they were finally allowed to move on in 1975 following the signing of a new disengagement accord, the crew left to guard the cargo ships were forced to occupy themselves by forming their own sporting contests and social gatherings, even developing their own bartering system and stamps for use among themselves. After eight years at anchor, only two of the 15 remained seaworthy when invited to set sail once more.

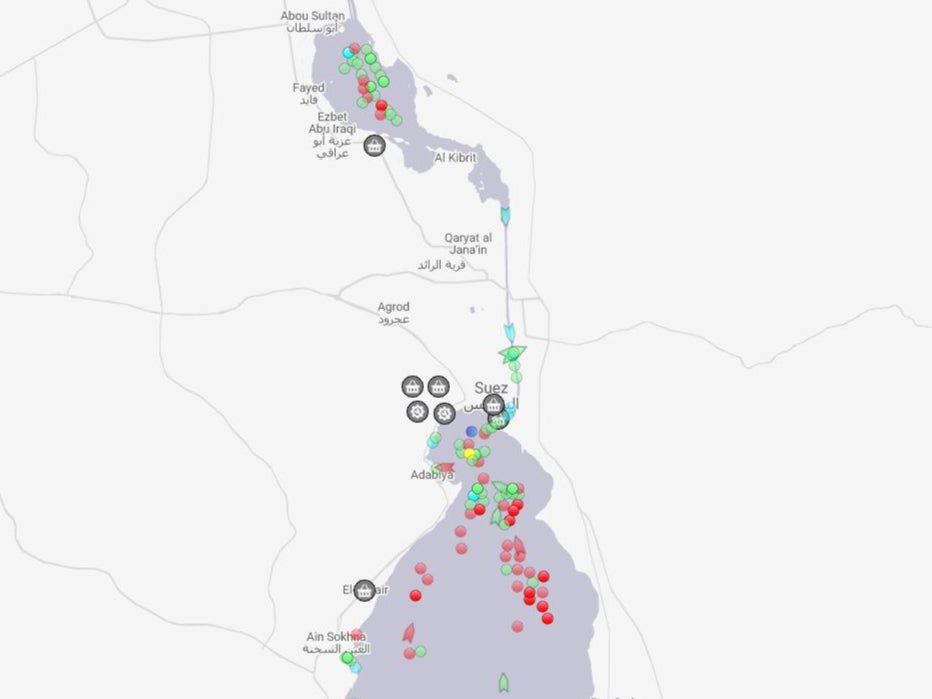

More recently, the Suez Canal has enjoyed steady trade – an estimated 50 ships passing along its length on a typical day and the Egyptian government picking up $5bn in tolls every year – and has undergone a series of improvements.

A $9bn project to broaden and deepen its Ballah Bypass off the main channel along a 22-mile stretch was commenced in August 2014, allowing 97 ships to pass every day and boosting transit times when it was opened a year later.

The Ever Given, the 1,300 feet-long ship at the centre of the current chaos, is operated by Taiwanese company Evergreen Marine and registered in Panama.

It was built by Japan’s Imabari Shipbuilding, has the capacity to carry 20,388 containers and was first launched on 9 May 2018, its current journey intended to take it from China to the Port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands before disaster struck.

The Ever Given was reportedly involved in a previous incident in February 2019 when it collided with a small ferry boat at the Port of Hamburg, Germany.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments